Cymatics

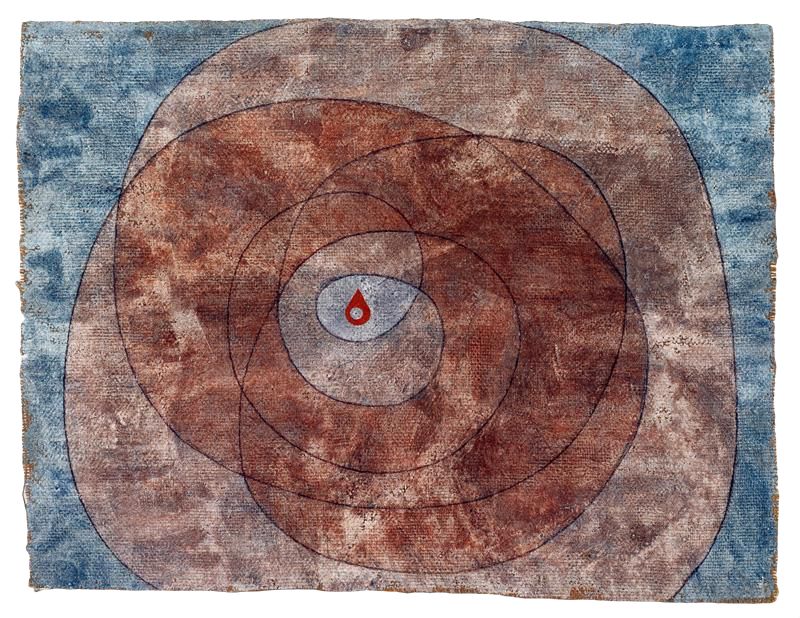

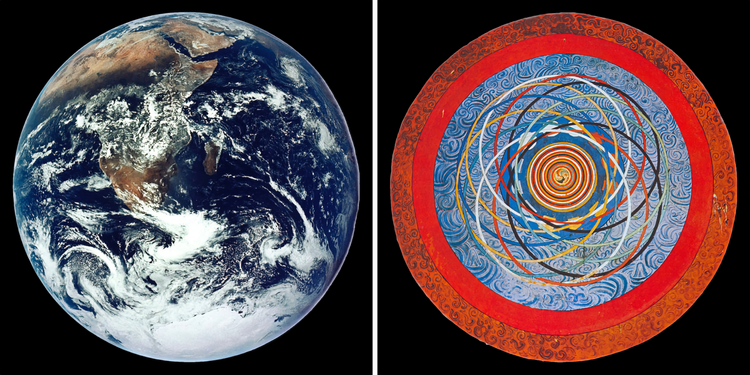

Is the photo on the cover of this book one of my drawings?

The answer is no. But it could be.

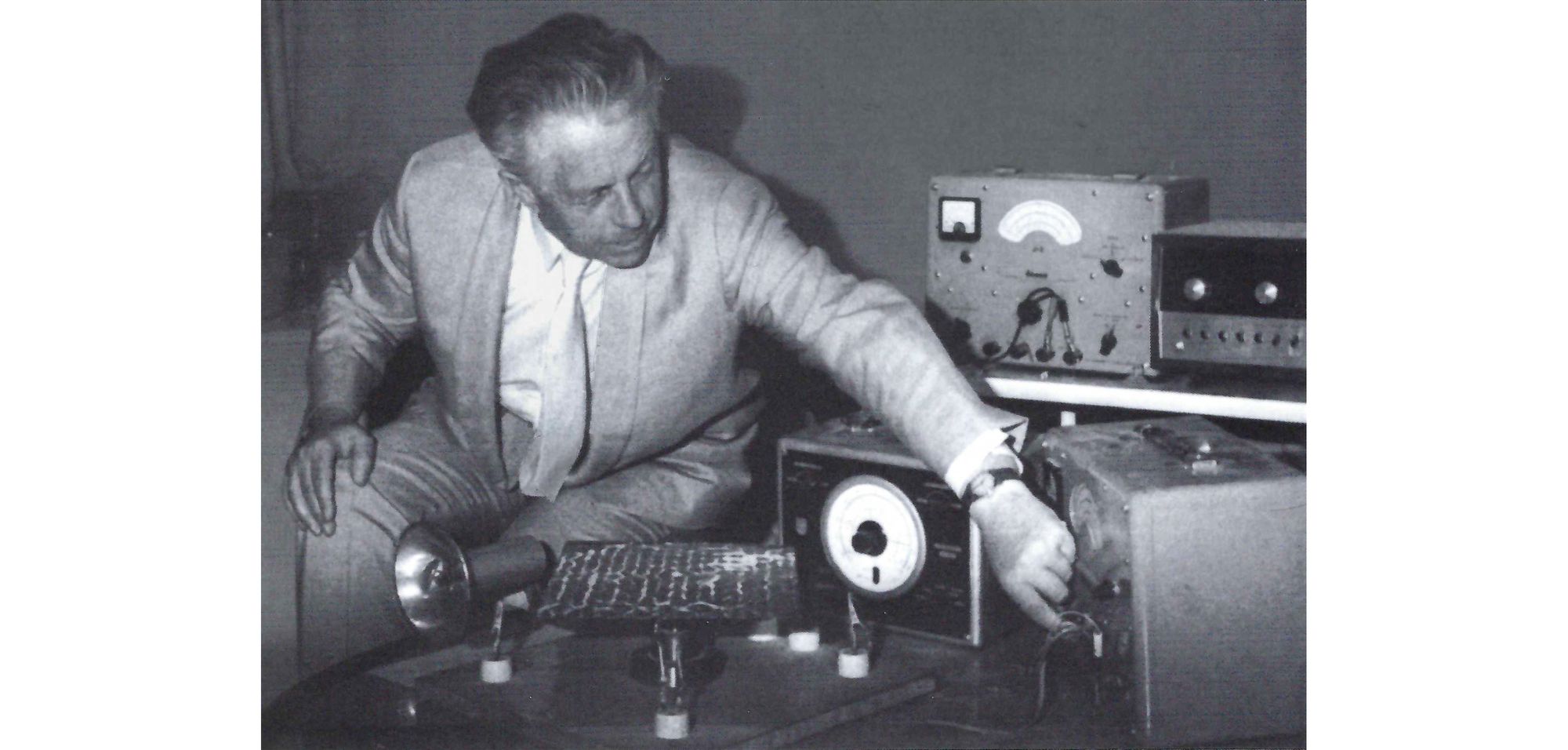

The image is one of many remarkable photographs taken by Dr. Hans Jenny, a Swiss medical doctor, natural scientist, artist, musician, and philosopher who spent 14 years meticulously researching what he called the “invisible formative processes” that underlie all physical forms. After receiving his medical doctorate degree, Jenny taught science for 4 years at the Rudolf Steiner School in Zurich. His book, Cymatics (from the Greek to kyma - “wave”), summarizes the thoughts and work of this modern day (1904-1972) Renaissance man.

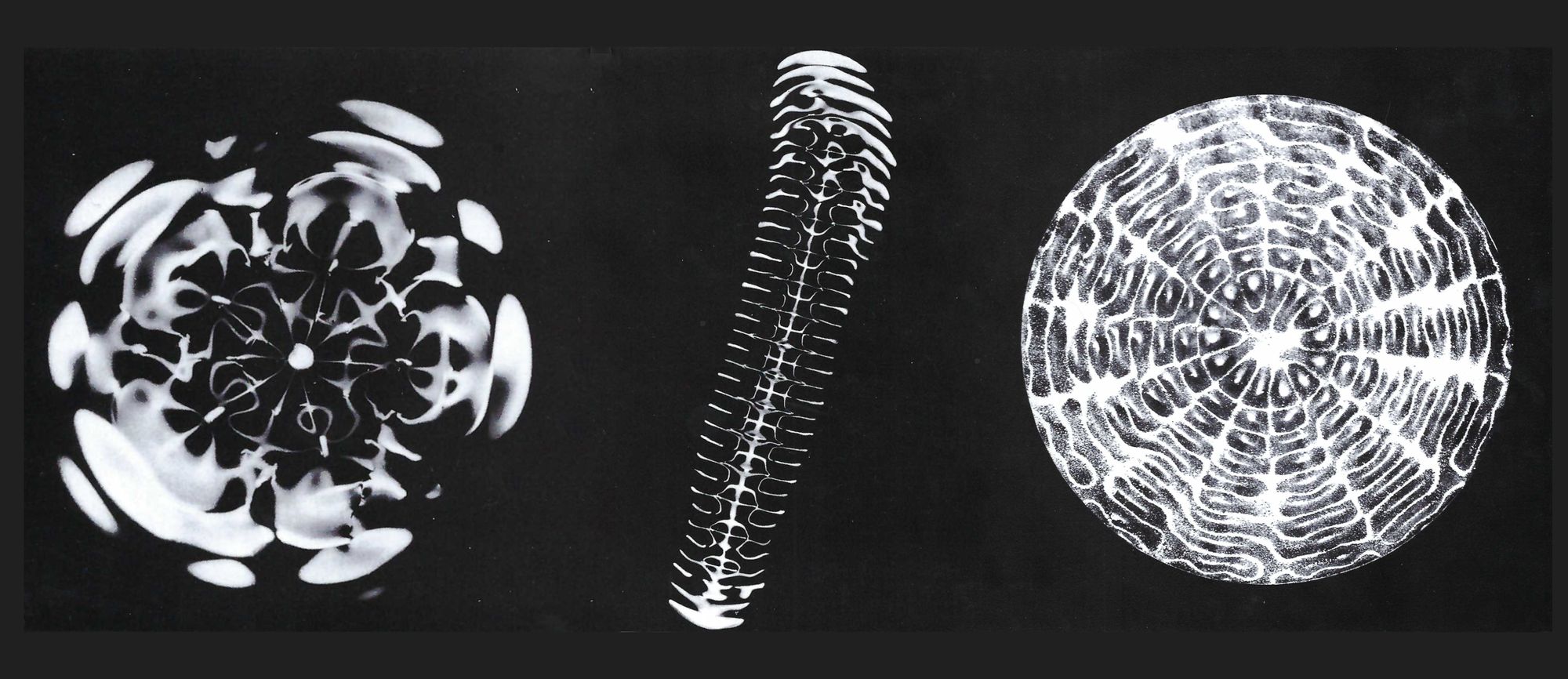

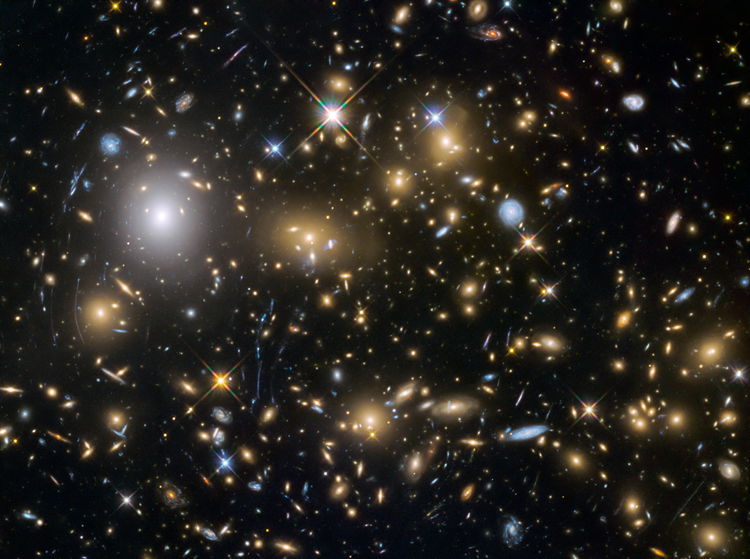

I discovered Dr. Jenny’s book later in my life, and with no pre-knowledge of his research, I was awe-struck to see many reflections of my existing drawings in his photographs of sand, powders, and liquids that were activated by varying frequencies of sound vibration to create temporary mandala, fractal, skeletal, dendritic, and wave patterns. The patterns resemble actual physical structures in both microscopic and macroscopic worlds. As the sound waves increase in frequency on the metal plates that Jenny used for his investigations, these structural patterns begin to pulsate and increase in intricacy. But when the sound waves cease, they immediately return to their original, non-patterned states.

The images below offer a glimpse into the nature of these invisible structural patterns that bear striking resemblances to familiar cellular structures. From left to right, they include 1) a celluar pattern of glycerin subjected to a low-level sound vibration, 2) a design, also from glycerin, that creates an almost spinal-looking energy pattern and 3) another cellular pattern, created from vibrating quartz crystals activated by a higher frequency than example #1. It shows the characteristic higher intricacy of organization.

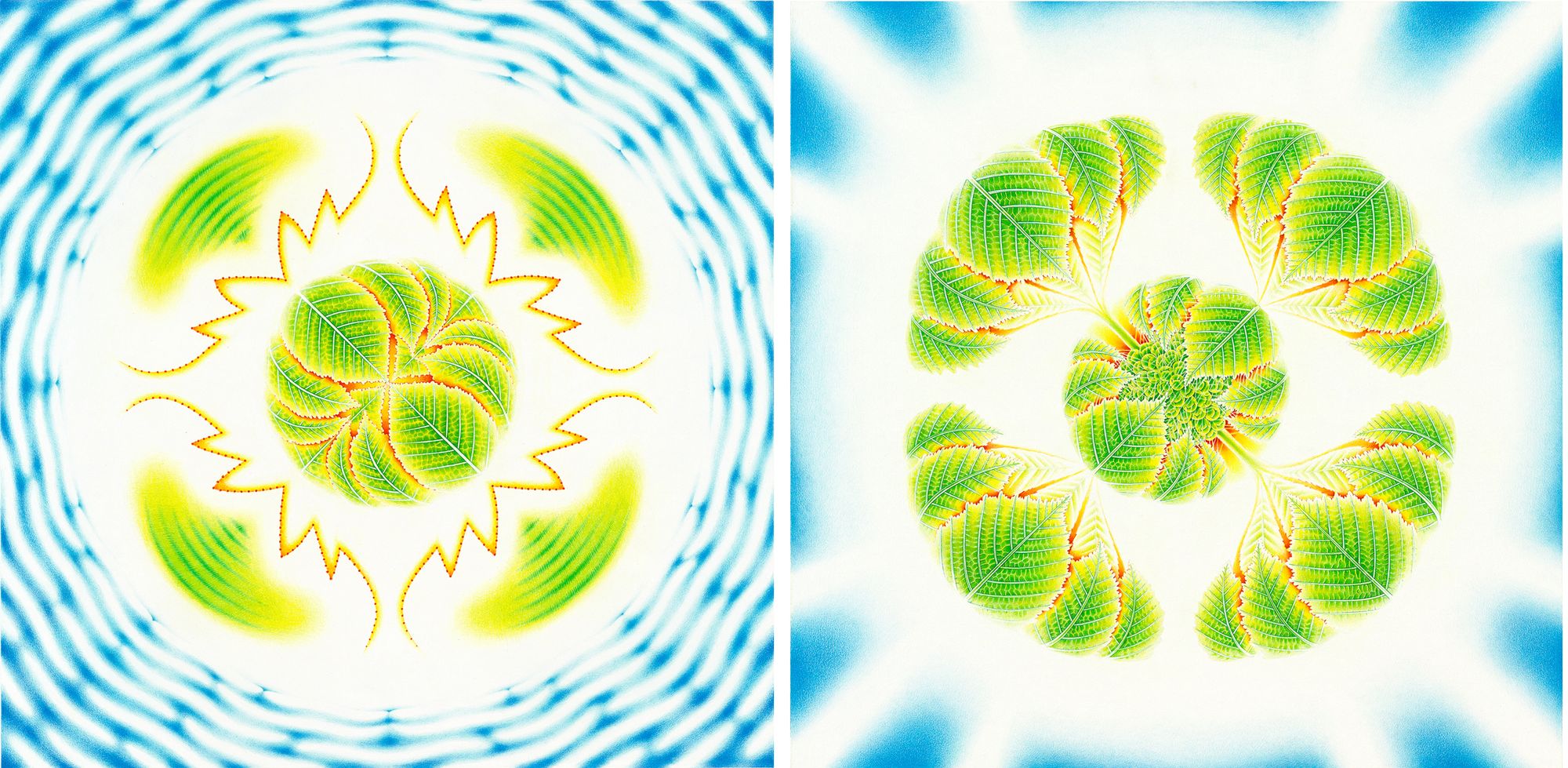

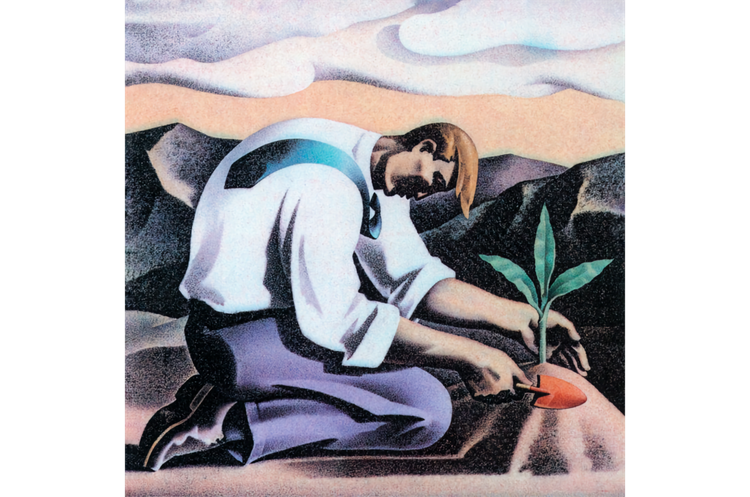

Years before—from my own experiences and observations—I had spontaneously chosen many of these ever-changing patterns of organization as the visual vocabulary for what became a life’s work project titled From Seed to Universe. I set aside this project several times when “daily life” intervened, but will be returning to and completing this project now that I’m more settled into my new life in rural Central Washington. In the From Seed to Universe drawings, I illuminate specific moments of time in a cyclical coming-into-being process of change that is overlaid on an invisible, creative core.

Early on, as the drawings for From Seed to Universe took shape, I discovered that “my” imagery was uncannily connected to the work of many other artists, poets, mystics, scientists, and philosophers throughout the world. I also learned that this universality of artistic and philosophical expression has existed for thousands of years. How did so many artists—living in different times and locations—spontaneously choose similar imagery to express the same ideas? I eventually stumbled on a quote by Joseph Campbell, a lifetime researcher of myth and archetypes, that explains this uncanny synchronicity very simply:

When you start thinking about these things, about the inner mystery, the inner life, there aren’t too many images for you to use. You begin on your own, to have the same images that are already present in some other system of thought.

— Joseph Campbell, USA, 20th Century

For 35 years I worked as both a medical massage therapist and a medical illustrator to help support my art life. This exposure to a new, specifically medical line of investigation at the cellular level expanded my existing holistic life view in a fascinating and practical way. I grew even more accustomed to understanding the world from two complementary perspectives: the physical component that we see and experience in our daily lives, and the invisible energy component that builds up and maintains outward forms from within. The knowledge I received from my in-depth medical and natural science studies eventually found its way into my “real” art, to influence, expand, and strengthen my artistic awareness and skills in ways I could never have foreseen.

For this unique educational opportunity, I am immensely grateful.

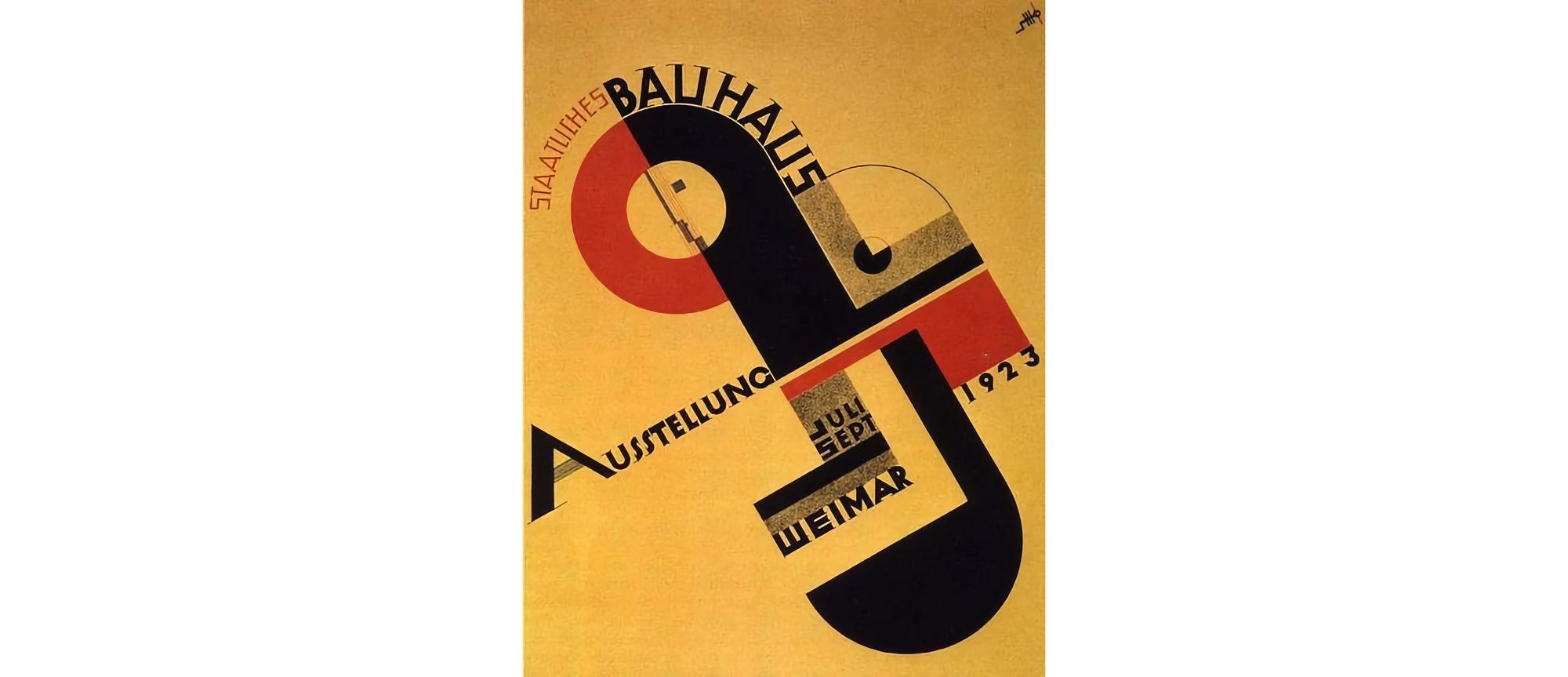

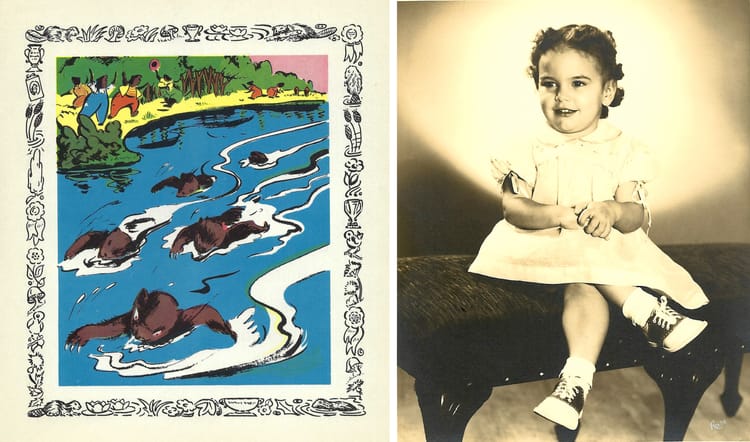

In the early 1920’s visual artist Paul Klee, (one of my many artistic heroes and heroines) began teaching at the Bauhaus, a progressive and highly innovative art school in Germany that welcomed a variety of perspectives among its faculty.

Klee’s official title at the Bauhaus was “Form” master in the bookbinding, stained glass, and mural painting workshops. It was while working at the Bauhaus that Klee was introduced to Theosophy and the concepts of German philosopher Rudolf Steiner by his Russian colleague Wassily Kandinsky, the author of the 1911 ground-breaking book Concerning the Spiritual in Art. It is no surprise then, that some of Steiner’s concepts would eventually find their way into Klee’s teaching.

In an extraordinary lecture to his students at the Bauhaus in 1923, Klee eloquently explained the basic law of all growth and form that verbally mirrored the content of Hans Jenny's 1960’s cymatics photographs of “invisible formative processes” 40 years later:

First life, then the shelter for it. That is the way it happens, even on the minuscule scale.

Creative power is ineffable. It remains ultimately mysterious.

In all likelihood, creative power is itself a form of matter, with the same senses as the more familiar kinds of matter. Yet it is through these familiar kinds of matter that it must reveal itself. It must function in union with matter. Permeated with matter, it must take on a living, actual form.

It is thence that matter derives its life, acquiring order from its minutest particles and most subordinate rhythms all the way to its higher articulations.

Let us therefore think not of form, but of the act of forming.

Member discussion