My Father’s Desk

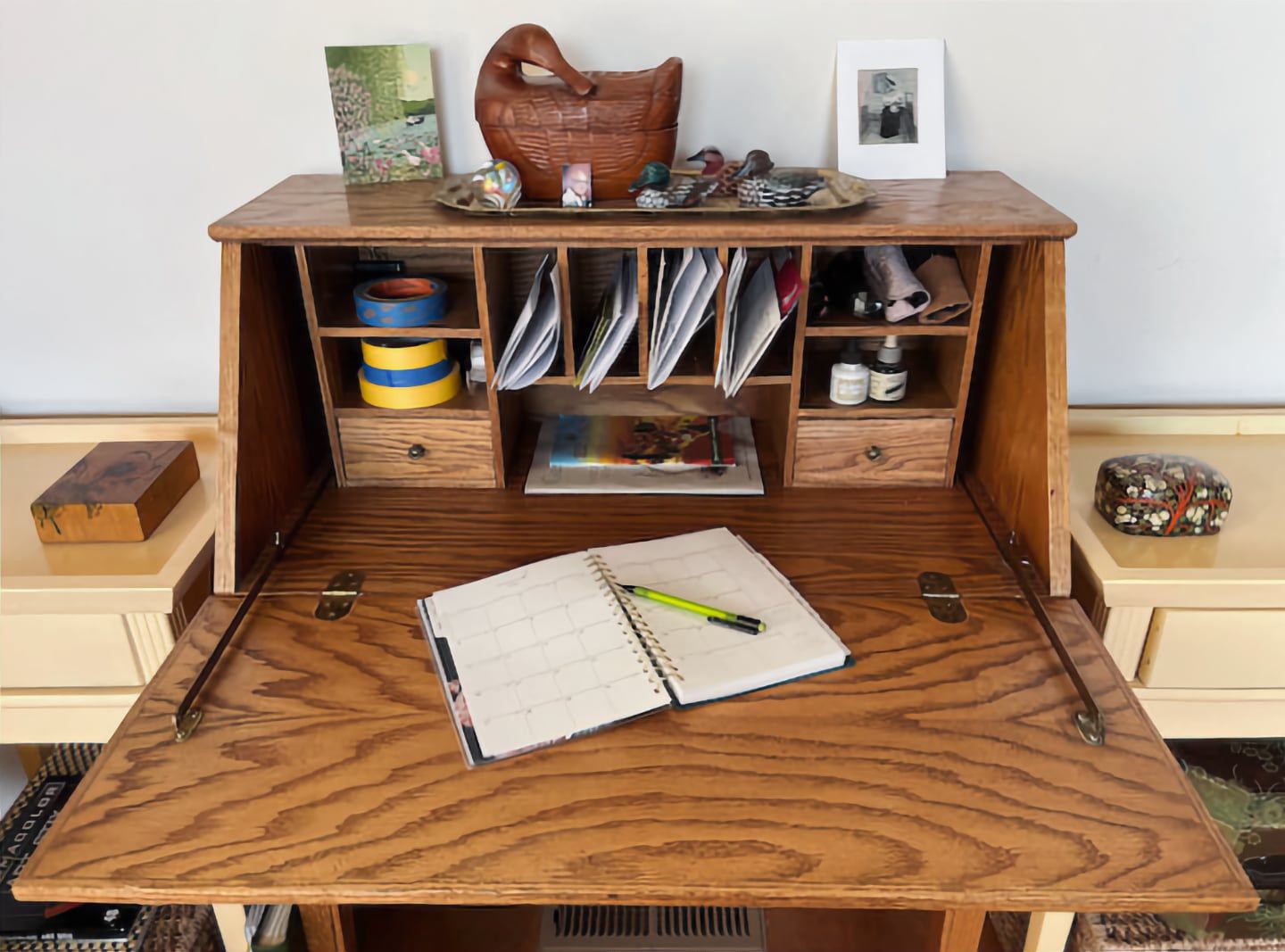

In the art studio portion of my Tieton live/work loft, my father’s old oak desk sits next to my drawing table, the place where I transfer my dreams, inspirations, and studies into their final forms. As a practical man (who was prone to tears and soft inside), my father would have approved of this location for his desk because my work space was set up to “get things done” on the earth plane level, in the same way that he lived his own life.

During my summer visits with my father in Kennewick as an adult, I sometimes noticed him sitting at his desk, carefully entering notes into a small, blue, softbound booklet. I had no idea what he was writing. But when he passed away, I found the booklet in his files and discovered that it was a banking record of numerous small settlements he had received over many years for a class action lawsuit. The suit sought compensation from his employers, whose job-related safety negligence had caused debilitating illness (asbestosis) for my ironworker father and his buddies as they sprayed clouds of toxic white asbestos insulation inside the structures where they worked. No masks. No goggles. Nothing.

The law firm in California that managed the suit kept the largest share of the compensation settlements. But over the years the separate, small checks that my father received eventually added up to a substantial sum. And as his only child beneficiary when he died, it was his posthumous monetary gift from these settlements that allowed me to buy my Tieton art loft. He would have appreciated that the loft was not a piece of paper, but something I could “get my hands on and use.”

Now, as I look over from my drawing table towards my father’s desk every day, I think of it as a symbol of how much he cared for me, even in the hardest of times.

My father noticed early on that I had musical ability along with visual art skills because as he told me more than once, I was always “drawing little pictures and singing little songs,” even as a young child. What he lacked in understanding for visual art, he made up for with his great love of music, which he freely shared with me.

For my fourth birthday, he bought me an inexpensive 45-rpm record player and a stack of unsalable (with reason) records from the small music store in Wenatchee. The music store owner most likely gave my father the records when he learned they were for me. My favorites were the nostalgic or sad sounding recordings. “The Everlasting Hills of Oklahoma” by the Sons of the Pioneers, some orchestral Strauss Waltzes, and the pinnacle of my personal four-year-old Hit List, “The Lord’s Prayer” by the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. I didn’t know what the words meant but I liked the serious and soothing harmonies of the music.

A few months before I turned five, my father found work on a bridge in Kennewick and we parked our 15-foot trailer in a “court” near the job site. One Friday night when he came home from work, my father told me that he had planned a special surprise for me that evening. And right after dinner, he grabbed a six-pack of beer, took my hand, and we walked across the dirt road to our new neighbor’s trailer. “He’s German,” was all my father said with a smile. After our neighbor welcomed us in, he and my father opened the beers, and our new German friend went to the back of his trailer and returned with a large bespangled accordion. He settled in to play rousing live polka dance music all evening to accompany the “beverages.” Finally, after the beers were exhausted, our neighbor again went to the back of his trailer to wake up his two elementary school-age children so they could come out and sing a few more polkas in German as the Grand Finale.

I was transfixed by that first exposure to live music, so my father and I returned to our neighbor’s house for music at least one Friday every month. Although he mentioned very little about his own childhood, I learned much later that my father had grown up in eastern Minnesota next to the Wisconsin border, surrounded by Scandinavian and German immigrant communities whose dance bands included lots of polkas that helped soften the effects of Depression era misery. I understood why he appreciated our German neighbor.

I learned to play the violin in 4th grade, but never lost my love for the sound of the accordion. And I proved it when I played traditional Balkan folk music for many years on my violin as an adult, with my accordionist music partner.

My father loved his polkas but also his “Mantovani Music” as he called it. Since both musical genres were so completely different, I could not imagine anything more unlikely.

For years, I always wondered where on earth my polka-dancing father heard and grew to love the music of his beloved Annuncio Mantovani, an Italian-born musician who relocated to England and formed his own orchestra during the 1930s. As the arranger and the conductor, he specialized in creating a lush, romantic, and highly nostalgic sound, and by the time WWII broke out, The Mantovani Orchestra was one of the most popular British dance bands, both in live performances and on BBC radio broadcasts.

Since my father served in Europe and North Africa during his WWII army years, the caressing sound of Mantovani on the radio must have provided the comfort he needed to weather the war’s tragedies as well as the personal sorrows he experienced in 1933, when his Minnesota family completely fell apart. His French-Canadian father disappeared and his gentle, soft spoken Norwegian-born mother died at age 41 having her 13th child. The remaining parentless children were farmed out to various sympathetic families and relatives. But as my father once told me, “It was the Depression and nobody wanted the boys.” No mother. No father. No home. No school. Nothing.

He was 15 and ended up living on the streets doing odd jobs with his older brother Johnny. One day, someone gave them some flour. They mixed it with water and made some pancakes. As my father described it to me many years later, “We were so hungry we thought they were the best damn pancakes we ever ate!”

Perhaps his love of music helped soothe his soul later on, but some things “don't get no better,” as the famous polka slogan says. I, his only child, was his shining beacon of comfort, even though I turned out to be “different” than expected.

Even though my father was the first to admit that he didn’t “know nothin’ about art” and never would, he was always proud of my talents and throughout my life tried to understand and support me, even though our lifestyles and world view preferences were so far apart that our relationship was often difficult, especially as I grew older. He liked his “huntin’” and his “fishin’” and a predictable small-town life with his ironworker buddies who shared his personal enthusiasms. I was the independent, freethinking, progressive-minded, world citizen explorer who loved art, travel, and the unfamiliar music and languages of foreign cultures.

My father and I often talked about “goin’ fishin’ together,” but of course, we never did. Finally, as he grew even older, we made a truce. One evening I arrived home to find a voicemail message from him. “Well, this is yer dad and I’ve been thinking. We ain’t never gonna go fishin’ and we both know it. So just do your own thing, I’ll do mine, and everything will be OK. I’ll always love you. Bye.”

For my father’s sake I started expanding my definition of “art” to include things I did “with my hands” that he could appreciate and feel more comfortable with. He still stayed away from more formal or public visual art activities. But to him my skills at designing and remodeling houses was art. My healing arts medical massage practice was art. My musicianship was art. And best of all, a good party with live music and dancing together was always art. For my 50th birthday party, I told my father that I had hired an Elvis impersonator as a joke for all my musician friends who believed that I would be introducing our band’s new singer. My father immediately sent me a check to make sure the “festivities” would be adequate. My father picked up his sister, my 80-year old aunt, and drove to Seattle for the party. And after the surprise “Elvis debut” my aunt ran to the stage to accept the trademark scarf gift that the “King” always offered to a fan.

I was 51 when I decided to get married. There were two live bands with lots of dancing, good food, and an array of American and foreign-born guests. One of my traditional Greek band music partners performed as the wedding party “Greek” Elvis impersonator. My father drank so much beer that he fell down dancing and dropped the sunglasses he wore to hide his wedding ceremony tears. He apologized by phone the next day, but I laughingly relayed to him what one of my wedding guests who grew up in Wisconsin told me about my father’s mishap: “If nobody fell down from drinking beer at our weddings in Wisconsin, we didn’t really call it a wedding!”

I keep my father’s photo and the card he carefully chose for my 50th birthday inside his desk in my Tieton art studio. And when I am tired or feel overwhelmed, I take out these mementos to restore my spirit. I always feel my father’s presence and remember, with gratitude, the way he always looked out for me one way or another, even in the hardest of times.