My Grandmother’s Quilts

For a few weeks every summer, I always loved visiting my maternal grandmother, Fern Conkel Snyder, who lived in a tiny, hand-built house at the edge of Sunnyside, Washington. The property had been farmland when she arrived from Nebraska with my grandfather and her three children sometime in the late 1930’s. But even though the town had gradually grown closer since then, her property still had enough wild cattails, garden flowers, large trees, and evening cricket sounds to keep an artistic and nature-loving child like me completely happy.

My visits often coincided with the times my grandmother would host her circle of sewing-adept women friends at her house, for what she called a “quilting bee,” a communal needlework arts tradition that she brought with her from rural Nebraska. Each woman would arrive at her house with individual quilt blocks that each had stitched together by hand at home. Next, all the blocks would be assembled into the final design and quilted by hand through a thin layer of cotton batting.

It was always a joyful time for my grandmother and her friends as they shared stories, laughter and talk during their work times. For them, these artistic afternoons combined with an atmosphere of mutual support from other rural women, must have felt like a welcome break from daily lives that were often filled with unforgiving drudgery. The women always ended their day’s work with ice cream and coffee, and my grandmother made sure to prepare a bowl of ice cream for me.

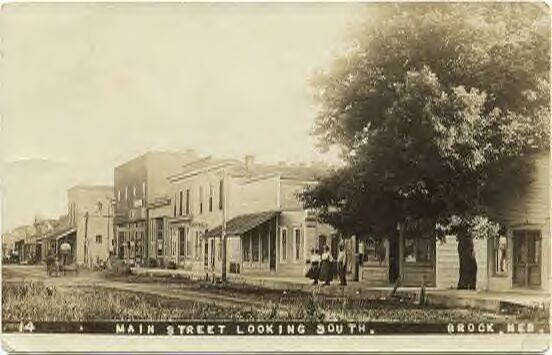

In the early 20th century, my grandmother Fern learned the art of quilting from her mother, Emma Lockwood Conkel, when her family lived on a farm just outside the small township of Brock, in southeastern Nebraska, just across the Missouri river from Iowa.

The Missouri-Pacific trains had been running to and through Brock since 1882, bringing a variety of manufactured goods—including bolts of commercially dyed or white cottons—to the dry goods stores (a quilter’s heaven!) along the route.

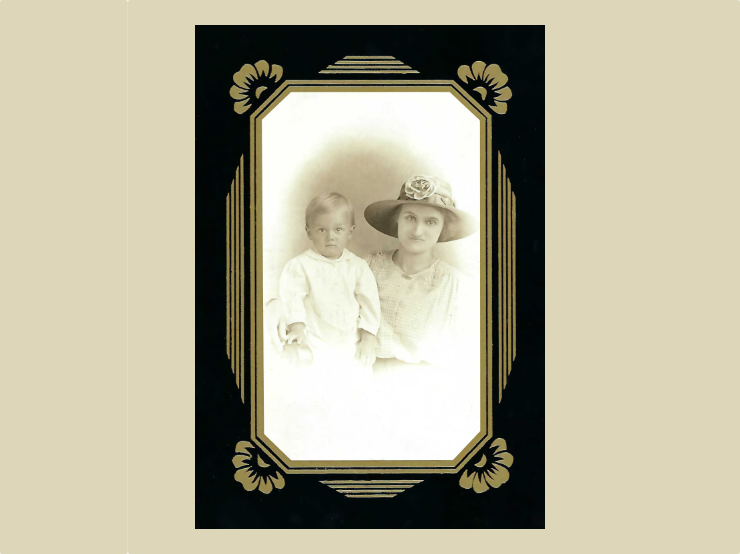

Sometime after 1900, my great-grandmother Emma bought the fabric she would eventually use for an unusually beautiful quilt she envisioned in her mind. Unlike most of the quilts at that time that were made from pieces of multicolored calico cloth salvaged from outgrown, repurposed girl’s dresses, Emma may have had extra funds available after the farm harvest to buy commercial cloth, and she did. She settled on only two colors for her quilt: a clear gold for the main block designs, and a soft white for the accents and borders.

In my early twenties my grandmother Fern (Emma’s daughter) passed away, and I inherited two hand-stitched quilts that she had stored away for many years. One was the elegant, minimalist, gold-and-white quilt that her mother Emma had made at an unknown time in the early 20th century. Her quilt is shown at the beginning of this post as the feature image. The other quilt was a traditional-style calico design that my grandmother had made.

I’m sure that since I was always drawing as a child and displayed a talent for meticulous sewing as I grew older, my grandmother must have sensed that I would be a responsible future caretaker for these two heirlooms. I’m also sure that my status as a potential beneficiary was “upped” by several notches in my grandmother’s mind when I won a first prize blue ribbon in the Yakima County Fair “youth division” sewing competition (at age 9) for my hand-hemmed tea towel and matching potholder.

Both quilts my grandmother passed on to me were beautiful but carried different emotional tones. With its design of bright, dancing, multicolored stars, my grandmother’s quilt projected an air of innocence and joy.

My great-grandmother Emma’s gold and white quilt conveyed a more thoughtful, quiet, and almost contemplative presence that was reflected in every aspect of the precise, uniform, and consistent quality of the overall workmanship. The combined effect was like the recognizable stamp of a personal fingerprint. Since she chose a restrained color palette and a simple but “uplifting” quilt block design, I often wondered if she had made the quilt as a lovingly crafted future wedding gift for my grandmother or had created it as a personal solace and memorial for her youngest child and only son, Odes Conkel, who died before his teens, sometime between 1910 and 1920.

As a child I never inquired about any quilt’s background story. But as an adult, I made a silent vow to someday investigate the name and history of both quilt designs. Sadly, with so many artistic projects and other responsibilities vying for my attention, my well-intentioned research idea gradually entered a long period of silent dormancy.

My grandmother’s quilts arrived in my life at a time when I most needed their inspiration, just as I was trying (unsuccessfully and miserably) to squeeze myself into a more conventional and “normal” lifestyle after my disillusioned departure from art school. This misguided decision did not work, of course, and I quickly realized that the imprisonment of creative gifts was not a healthy solution. I needed to find a new artistic direction—anything that would help awaken my strangled soul—and fast!

Although I had not done any sewing in years, with the multicolored presence of my grandmother’s quilts nearby and alive in my mind, I suddenly developed a longing to start sewing again. I bought a used commercial sewing machine along with yards of cotton cloth and began adapting traditional quilt patterns to the design of handbags, aprons, table runners, and pillows, which I later sold through Seattle gift stores. An agent saw my “line” and asked if he could represent my products on a wider scale through his showroom in California. And a Seattle interior designer commissioned me to supply décor for residential and commercial clients.

The name of my one-woman home business was “Joseph’s Coat,” a reference to my grandmother’s multicolored quilts and to “Joseph and His Coat of Many Colors,” a famous bible story I read as a five-year old, in which Joseph eventually triumphs over adversity.

I didn’t receive a “higher” art school degree for my non-academic design efforts. But I did retrieve my spirit from self-imposed bondage and dedicated its awakened energy to future artistic explorations.

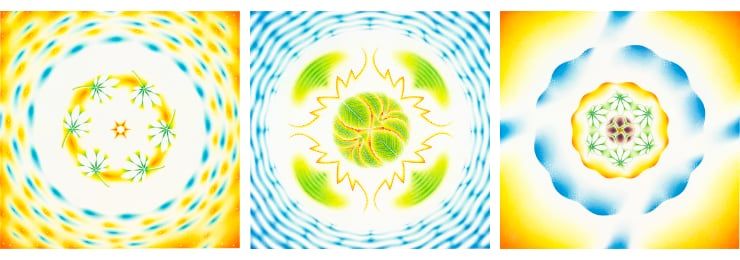

Many years later, when my artistic expansion had become more focused and I was working on two projects with a “tree” theme, I discovered some research in one of my art books about a worldwide symbol known as the Tree of Life, that has spontaneously appeared since ancient times in the art, religion, and mythology of diverse cultures. The Tree always represents the creative forces of the universe and the cycles of life that surround and sustain us all.

Without knowing anything about this symbol’s well-researched history, I realized that like other artists throughout the world who had lived and worked in different times and locations over centuries, I had also unconsciously chosen the philosophical message of the Tree of Life as an inspiration for my own art.

Both quilts that I inherited from my grandmother eventually began to fall apart from years of use, so I salvaged stable portions from each one, rebound the edges by hand, and framed them as the fine art they are.

At the same time, I finally decided to fulfill my earlier vow to research the names of the quilt block patterns that my grandmother and great-grandmother had chosen long ago. I consulted with a fiber-arts friend who had stacks of books on traditional quilt designs, and after some focused browsing, we found the names of each pattern.

My grandmother Fern’s multicolored dancing star quilt pattern was called “Star of David,” and my great-grandmother Emma’s elegant gold and white design—the one that seemed to carry a “thoughtful, quiet, and almost contemplative” presence—had two names.

The first was “Basket of Flowers” and the second was “Tree of Life.”

Member discussion