Paintings for the Future

I paint what I cannot see with my physical eyes.

— Hilma af Klint

Exhibition

On October 12, 2018, when the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York presented an extraordinary exhibit of stunningly vibrant paintings created by a mostly obscure, early 20th century Swedish artist named Hilma af Klint, (1862-1944) no one could have predicted that the showing of her vast series of interrelated artworks—titled “Paintings for the Future”—would become the most successful and well-attended event in the museum’s history. Before the show closed on April 23, 2019, more than 600,000 visitors would pass through the museum’s spiraling exhibition space to stand awestruck before af Klint’s abstract, enigmatic, and visionary illuminations of invisible worlds beyond the boundaries of everyday reality.

Unfortunately, I was not able to join the constant stream of artists and art lovers that filled the museum’s exhibition ramps during the exhibit, but several of my friends did attend and immediately sent me on-the-spot photos and glowing reports of their experiences. Each of them also told me that in many of Hilma’s paintings they recognized uncanny similarities to my own work. But up until the time of the Guggenheim exhibit, I (like many others) had never heard of Hilma af Klint.

Who was this determined and self-directed woman who created an extraordinary body of groundbreaking artwork that she chose to keep mostly secret from public view for her entire life?

Early Years

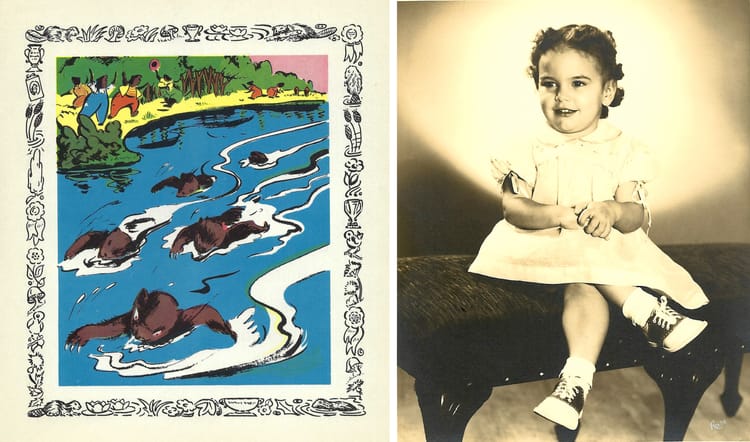

Hilma af Klint was born Stockholm, Sweden in 1862 and began her art studies at The Royal Academy of Art in 1882, at the age of twenty. Her initial art school curriculum required her to create works with mostly “traditional” themes: portraits, detailed botanical drawings, and landscapes.

But although Hilma af Klint was among the first generation of Swedish female artists that shared studio space with male colleagues, like other women artists of the era she was still taught that “copying” was a more appropriate use of women’s artistic abilities than “innovating.”

It did not take long for af Klint to begin abandoning the inequitable restrictions of her academic training to explore deeper and more expansive world views and non-conventional forms of artistic expression.

Theosophy and transition towards abstraction

Around the turn of the 20th century, inspired by her interest in spiritualism after her younger sister Hermina passed away, Hilma joined the Stockholm branch of the Theosophical Society, a worldwide educational association founded in New York in 1875. The Society encourages open-minded inquiry and study of world religions, philosophy, science, and the arts, with the goal of fostering understanding of the spiritual aspects of life and humanity. From its beginning, the Society has endorsed complete freedom of individual inquiry for its members—along with an expectation that each member would respect the existing belief systems of others.

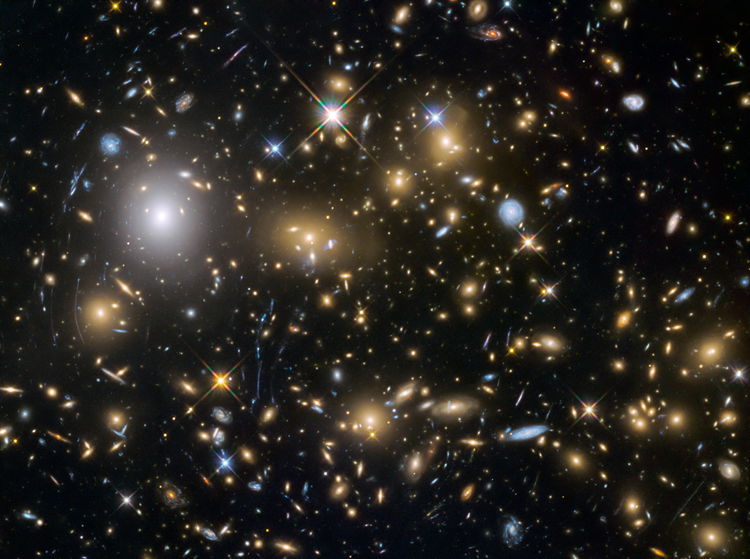

Theosophical ideas and educational resources (book publishing, lectures, access to library materials and space for meetings) were especially attractive to members of Stockholm’s artistic and literary circles, where independent thinking was already welcomed, accepted, and valued. In addition, new scientific discoveries and theories emerging around this same time—including x-rays, the electron, radio waves, and the theory of evolution—only amplified and strengthened the Theosophical view that invisible but powerful forces existed beneath outward forms. All these complementary streams of inquiry and discovery may have combined to subliminally influence af Klint’s artistic path further towards abstraction.

Additional artistic inspiration

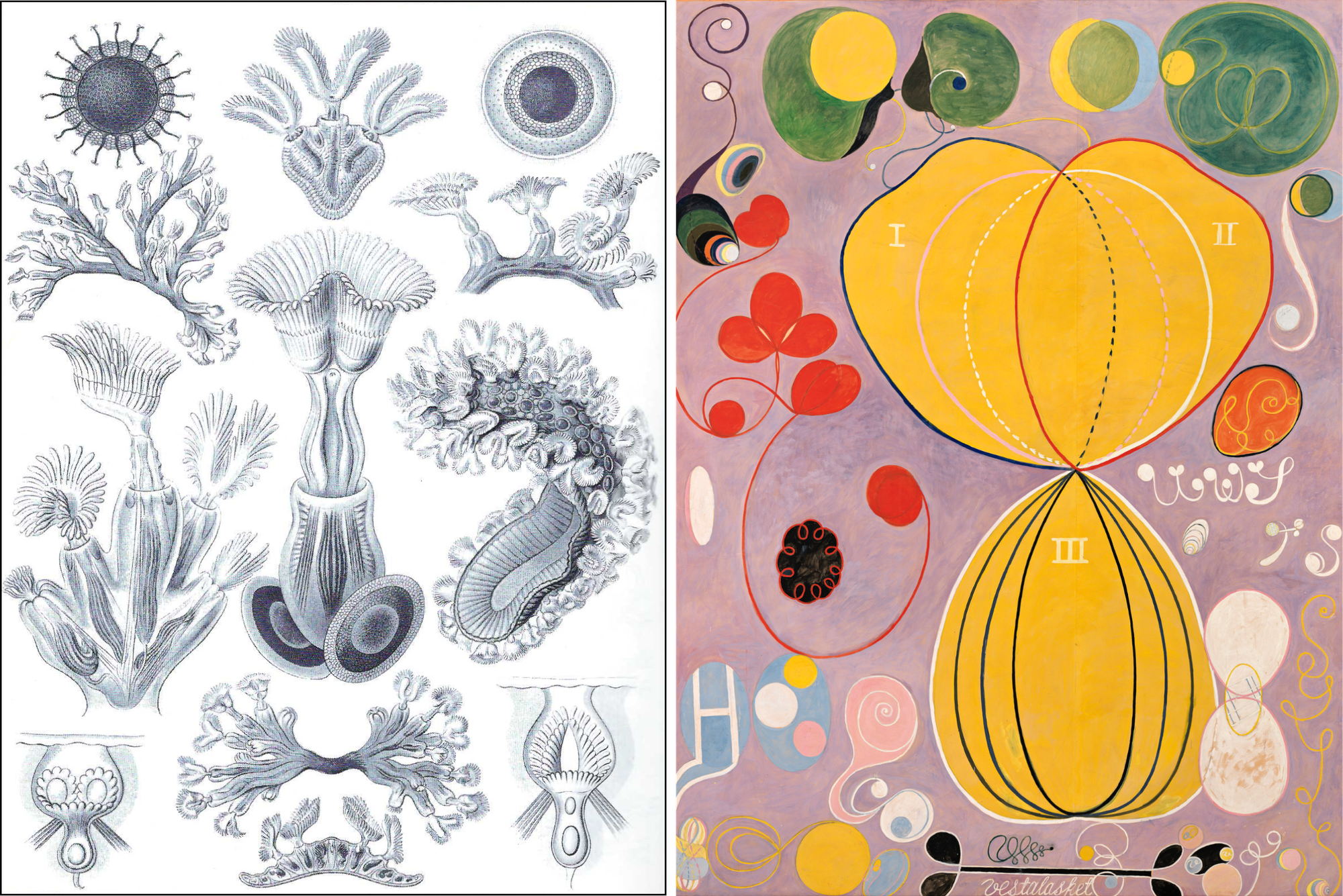

In 1904, around the same time that other invisible phenomena were being investigated and discussed more widely among the general population, Ernst Haeckel, a German-born biologist, naturalist, artist, philosopher, and doctor, published a book of 100 exquisitely detailed illustrations of microscopic sea creatures that also lived beyond the view of the naked eye. The breathtaking beauty of the many living “art forms in nature” that Haeckel illustrated resembled structures that appeared later in several of af Klint’s abstract paintings:

Activities of “The Five”

Between the years of 1896 and 1906, af Klint and four other like-minded women began meeting regularly as “The Five” to strengthen their communication with the “High Masters of Consciousness” (their term) that oversaw the workings of invisible worlds. The women used various techniques to facilitate these inquiries: prayer, benedictions, readings from the Bible and esoteric texts, seances, and automatic writing.

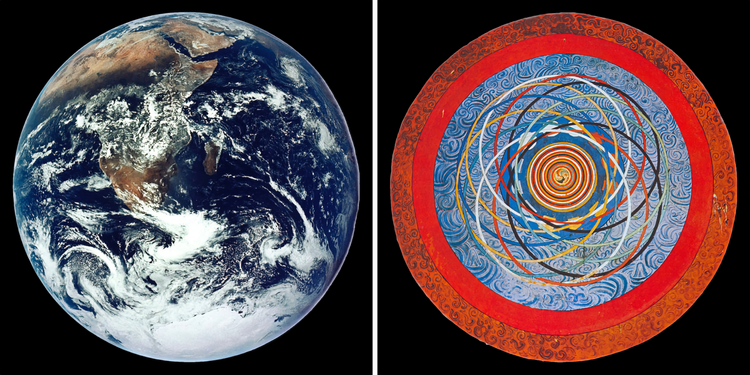

The imagery that appeared through trance state activation included biomorphic forms, depictions of energy movement between different design elements, double helixes (long before the discovery of DNA), messages encoded within an esoteric, symbolic alphabet that accompanied the imagery, and nearly endless spiral design variations.

Hilma af Klint documented many of her own spiral images in private sketchbooks as well as in her large-scale paintings. Throughout her lifetime, the spiral was the most recurrent image in her work.

The Great Commission

In 1906, when af Klint was chosen by her women colleagues to be the medium during one of their group meetings, she reported that she had received direction from one of the “High Masters” to create of a series of large-scale paintings titled “Paintings for the Temple”, which would eventually be installed in an unknown temple sometime in the future. Hilma described this exchange of information as a “commission” that she later documented in writing in one of her personal sketchbooks:

I was offered a commission and I immediately replied yes. This became the great commission, which I carried out in my life.

As promised, Hilma af Klint completed the commission she accepted and spent many years attempting to have an exhibition space or “Temple” built to house and share this work as a gift to humanity. But despite her efforts, it was a great disappointment to her that her gift of art—and the deep spiritual insights it represented—was not welcomed by the public during her lifetime. For many years, af Klint painted in near isolation away from the European avant-garde. Finally, accepting the reality that she and her work would likely not be understood by humanity at its present level of awareness, she stipulated in her will that her abstract work should be kept out of the public eye for 20 years after her death.

It would take 74 years for her work to find its “temple” at the Guggenheim Museum.

In my next Art Nun Journal post, I’ll be writing about the extraordinary details behind af Klint's long-overdue and unforeseen artistic triumph, along with my personal observations about the parallel artistic connections that exist between her work and my own.

In the meantime, the beautifully photographed and evocative documentary film, Beyond the Visible - Hilma af Klint, will provide you with a visual journey through her life, world, and art.

Make yourself a cup of tea and settle in.

This 94-minute documentary is also available on streaming services such as AppleTV, the Kino Film Collection, and Amazon.

Member discussion