Illuminating the Invisible

Those granted the gift of seeing more deeply can see beyond form and concentrate on the wondrous aspect hiding behind every form, which is called Life.

— Hilma af Klint

Hidden Forms

I discovered the work of turn of the 20th century Swedish artist Hilma af Klint later in my life, through her “Paintings for the Future” exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum in 2018. And with no prior knowledge of her artistic training or philosophy, I immediately understood her artistic language.

The swirling spirals that af Klint repeatedly depicted in her paintings and private sketchbooks had already been part my own artistic vocabulary for more than 40 years, ever since an unusual and transformative dream appeared to me in the spring of 1974.

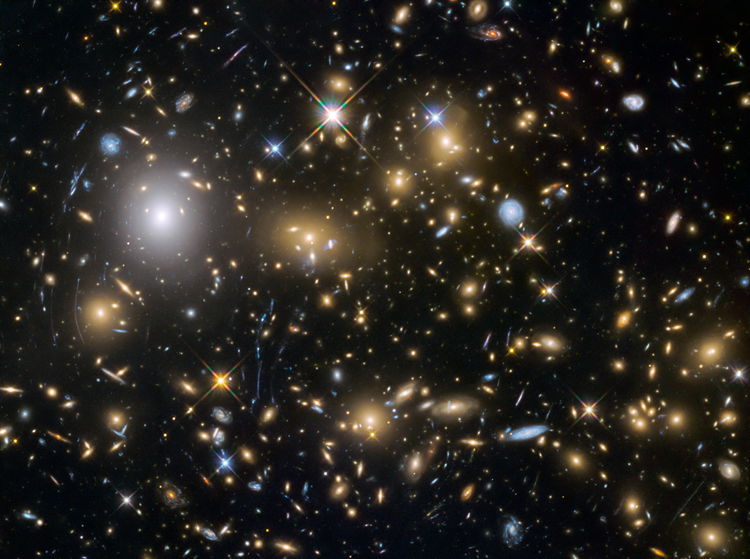

The dream—at least that is how I initially described it to others—had the form of a vast, revolving, spiral galaxy that drew me into its core and instantaneously altered my existing world view and artistic direction in ways I could never have imagined. Later, as I began seeking out readings that might help me decipher the dream’s meaning, I learned that since ancient times the spiral and its many variants (the helix, the intertwining double helix, and the vortex pattern) have always represented the invisible creative principle that is alive and continually at work in the universe, in both microscopic and macroscopic worlds.

Through the portal of my Passage artwork above, you’ll find additional information about my galaxy dream and the new art direction that grew out of it.

In 2010, long before I knew of Hilma af Klint, I created a website that included examples of artworks inspired by my dream. It wasn’t until the 2018 Guggenheim exhibit that I recognized how I had unconsciously chosen many of the same artistic symbols and themes that af Klint had incorporated into her paintings, more than 100 years in the past.

There is no rational explanation for the parallel artistic imagery that Hilma af Klint and I both unconsciously chose. But as time passed and I researched our connections further, I discovered that artists from diverse cultures and spiritual traditions have repeatedly used the same symbols to express shared ideas–even when separated by centuries of time and physical location.

To help clarify how this spontaneous replication process works, I am reposting (from an earlier entry in this journal) an explanatory quote by Joseph Campbell, a tireless researcher and author who spent his entire life documenting the origins and history of worldwide myths and artistic symbols in both written and visual form.

When you start thinking about these things, about the inner mystery, the inner life, there aren’t too many images for you to use. You begin on your own to use the same images that are already present in some other system of thought.

—Joseph Campbell

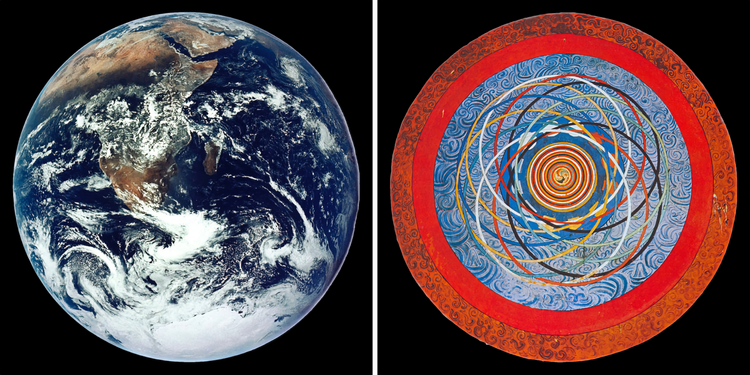

The two quotes below—taken from the writings of two mystics who were “separated by time and physical location”—confirm Campbell’s observations: The first quote is by fifteenth- century Sephardic scholar, rabbi, and writer Moses Cordovero, and the second is by Hilma af Klint. To complement the eloquence of both their quotes, I accompany them with one of my color drawings that compresses each of their written observations into a single, visual form.

I am a mustard seed in the middle of the sphere of the moon, which is itself a mustard seed within the next sphere. So it is with all spheres, one inside the other, and all of them are a mustard seed within the further expanses.

—Moses Cordovero

At this moment I have the knowledge of—in the living reality—that I am an atom in the universe that has access to infinite possibilities of development. These possibilities I want to gradually reveal.

—Hilma af Klint

Like Cordovero and af Klint, I am one more artist who was granted the ability to think about “the inner mystery and the inner life.” I still pay attention to the ongoing, intuitive wisdom of this gift that is always present and alive within me.

Limited Consciousness Expanded

Every time I succeed in finishing one of my sketches, my understanding of humanity, animals, plants, minerals, or the entire creation, becomes clearer. I feel freed and raised up above my limited consciousness.

—Hilma af Klint

The visible world in all its diversity was the starting point for af Klint’s artistic education and my own. Even in her art school days, she had the ability to infuse her botanical and other natural science subjects with a unique vitality.

In my own life I followed a similar path of artistic development that also began with the documentation of the visible world. With a few exceptions, I often joked with friends that planting a garden and observing the sprouting of seeds had provided me with more of an education than anything I learned in art school. Also like af Klint, for most of my adult life I’ve followed an independent art path that I consciously separated from all labels and other “group” identifiers.

The examples of artwork in the gallery below illustrate a few of the similarities that exist between af Klint’s early artwork and my own.

Indifference, Condescension, and Rejection

Although many of af Klint’s early 20th century artist contemporaries (Vasily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and Paul Klee) were also Theosophists whose abstract symbolism was eventually acknowledged and accepted, the same open-minded standards were not extended to af Klint’s work. Since she initially shared a studio with other graduates of the Royal Academy of Art, it may have been difficult for her to keep her spiritually influenced, abstract works entirely private. When several of her more conservative studio mates learned that her new imagery was inspired through mediumistic sources, they immediately disapproved, labeling it “inappropriate.”

Because af Klint’s spiritual abstractions were the result of direct mystical communication instead of the more “intellectual” investigations that other artists began to use later to inspire their own artistic expansion, her work might have been perceived by the existing, (male dominated) artistic hierarchy as a threat to its authority.

But it is also just as likely that she was ignored and marginalized simply because she was a woman.

Even respected Theosophist Rudolf Steiner was not immune from viewing af Klint’s spiritually based art with the same condescending and dismissive attitude that she had encountered before in other settings. In 1908, when she contacted Steiner to arrange an in-person visit to her studio to view her work and discuss possible options for exhibiting it, she was surprised to discover that he was also uncomfortable with the “mediumistic” origins of her work. As a result, he declined to fully endorse or help promote it.

After this sobering “audience” with Steiner, af Klint abandoned work on her Paintings for the Temple project for four years and did not return to completing the last pieces in the series (the “Altarpieces”) until 1915. She then turned her attention to creating smaller scale paintings and a private collection of illustrated notebooks that documented her artistic work philosophies in detail.

Plans for a Temple

Af Klint envisioned that her Paintings for the Temple artworks would someday be installed in a more contemplative setting than a conventional gallery or museum. And in one of her later notebooks (from 1930-31), she included drawings of her own concept for just such a building.

The structure would be round and would consist of three stacked rings that tapered upwards to the highest level. Visitors would progress in a spiral shaped movement between the three circular levels, which were built around a central tower that contained a spiral staircase. The highest level would open to an observatory that looked out to the heavens.

I believe it was no “coincidence” that in 1880, af Klint created a detailed drawing of a spiral staircase that seemed to foretell her vision of housing her life’s work in an unusual, circular, exhibition venue.

Bequeathing her Legacy

Shortly after her death in 1944 at the age of 81, Hilma af Klint’s studio on the small island of Munsö was demolished, and her life’s work of 1,200 paintings and drawings, together with more than 124 of her illustrated notebooks, were bequeathed to her nephew, Erik af Klint. After he was unsuccessful in locating a museum in Sweden that would accept his aunt’s work, the entire collection was packed away in Erik’s unheated attic, and, following the written instructions that af Klint left behind, it remained unseen until 1966, when Erik and his son Johann took her work out from storage to properly photograph it for the first time.

To preserve and manage his aunt's artistic legacy, in 1972 Erik af Klint established the Hilma af Klint Foundation. The foundation's mission is to encourage academic research about her work and develop collaborative arrangements for public exhibition purposes. By incorporating these values into their outreach, the foundation helped raise af Klint's visibility within European academic and artistic circles.

Throughout her life, Hilma af Klint remained highly protective of her spiritually based paintings, refused to allow them to be individually broken up for sale, and clearly specified that they should remain unseen by the public until twenty years after her death—when she hoped humanity might be more attuned and receptive to the mystical insights she offered through her work.

In 2018, af Klint’s exhibition plans would finally be translated into reality in a museum thousands of miles from her birthplace, thanks to the untiring and dedicated work carried out by a visionary art lovers who initially knew nothing about her or the exhibition plans she had documented in her notebooks 88 years in the past.

The way in which this enormous, collaborative achievement was orchestrated behind the scenes and eventually completed reads almost like a chapter taken from a psychic, science fiction novel.

Hilla Rebay, Nonobjective Art, and the Guggenheim Museum

In July of 1930, before Hilma af Klint started to sketch the temple she envisioned for her artwork, an artist living in New York City, Hilla Rebay, had already arrived in Europe with philanthropist Solomon R. Guggenheim and his wife Irene to meet artist Vasily Kandinsky. The purpose of the meeting was to explore possibilities for purchasing some of Kandinsky’s paintings for Guggenheim’s art collection.

Kandinsky’s book On the Spiritual in Art had already caused a sensation within Europe’s avant-garde art circles when it was published in 1911, and by the time the Guggenheims arrived in Germany to meet him, he was a well-known and respected figure in the modern art world. Hilla Rebay referred to this form of art as “nonobjective” because it contained no recognizable ties with visible reality. She further clarified its meaning as the “art of the future” that had the capacity to educate and uplift humanity. Rebay publicly championed this view with almost evangelical zeal.

Like Hilma af Klint (who was completely unknown to her), Hilla Rebay had a Theosophical world view and was already an established nonobjective artist and portraitist when she immigrated to New York from Germany in 1927, with goals in her mind for promoting a greater appreciation of nonobjective art and seeking out exhibition possibilities for it in her new homeland. With her impressive networking skills, she soon became a familiar figure within New York’s artist and patron circles. And when Irene Guggenheim commissioned her to paint a portrait of her husband Solomon, Rebay shared some of her crusading enthusiasm for nonobjective art with him during his sitting for the portrait. Guggenheim wanted to learn more, and Rebay, as always, was ready to answer any questions he had.

It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship and professional collaboration. Guggenheim soon hired Rebay to act as his personal artistic advisor, and under her direction began to systematically acquire a vast collection of nonobjective art from artists throughout the world.

In the early 1930’s, Rebay continued her efforts to find public venues for exhibiting Guggenheim’s nonobjective art collection. But since few exhibition resources existed, pieces from Guggenheim’s holdings were temporarily installed inside his private apartment suites in the Plaza Hotel, where visitors could view paintings by prior appointment.

By 1937, Guggenheim’s art collection had grown too large to house in temporary quarters. It was time make plans for building a real museum. In 1939, the Guggenheims established an official foundation for this purpose, and in 1943, Solomon Guggenheim and Hilla Rebay contacted well-known architect Frank Lloyd Wright, asking him to design a museum that would reflect the visionary ideals of Guggenheim’s collection. In the introductory letter, Rebay summed up these ideals to Wright in her usual unique and emphatically direct style:

I want a Temple of the Spirit! A Monument!

—Hilla Rebay

Wright accepted the offer, and quickly brushing off the harsh comments he received later from less visionary critics—who insisted that the museum’s inverted, spiral-shaped design looked like a “washing machine,”—he countered by publicly announcing that he would call his planned museum an “Archeseum…a building in which to see the highest.”

It would take Wright sixteen years of revisions to fulfill Rebay’s request for a museum “temple”—which uncannily incorporated many of the same design elements that the (still unknown) Hilma af Klint had already depicted in her 1930’s notebooks.

On October 21, 1959, the Guggenheim Museum of Art officially opened. But it would take another fifty-nine years before af Klint’s prophetic artworks would be installed for the Paintings for the Future exhibit.

Thanks to the tireless, visionary dedication of Hilla Rebay, Solomon Guggenheim, Frank Lloyd Wright, and hundreds of additional supporters, Hilma af Klint’s artistic gifts to humanity would finally be welcomed and appreciated, more than 100 years after they were created.

The temple was built. And af Klint’s long-awaited audience did arrive.

Member discussion