My Mother's Memorabilia Box

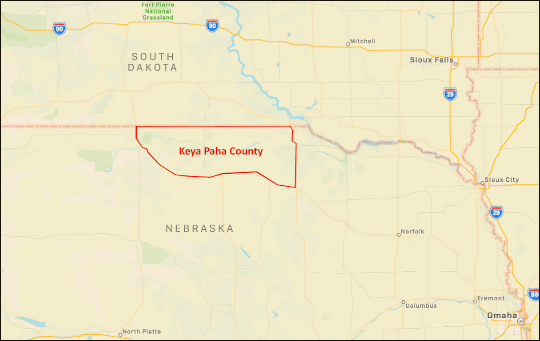

Sometime during the school year of 1932, a young teacher in Nebraska’s rural Keya Paha County led her 3rd grade students in creating small art booklets, with hand-cut lettered titles on the covers and colored drawings inside. My mother, Verda Jewel Snyder, the daughter of my grandmother Fern, was among her students. My mother’s booklet cover and her drawing of a meadowlark inside are both shown together above.

The Depression was progressing full speed ahead in 1932, and it was a miracle that my mother’s teacher, Etta M. Newland, was wise and compassionate enough to include art activities in her students’ education at a time when they and their families were suffering from the deprivations of that era—and art was too often considered a useless, impractical “luxury.” Wearing a dapper cloche hat from the early 1930’s, Etta Newland is pictured in my mother’s school class photo (below) in the back row, far left. My mother Verda is shown at age 9, in the front row of younger students, third from the left. She is the one with the high forehead.

According to one of the few memories of the Depression that my mother related to me much later when I was an adult, at the time the school photo above was taken, she and her family were living in a repurposed, “run-down chicken house” in a wind-blown, parched, flat prairie landscape. My mother said that for “health” reasons, the parents of all her schoolmates would not allow their children to play with her.

Although Etta Newland’s family lived in the far northern region of Keya Paha county close to the South Dakota border, she attended high school in the county seat of Springview, about 25 miles to the south. She was one of the graduates of an innovative high school educational program in Nebraska that was initiated in 1912, titled “High School Normal Training”. This program allowed motivated students to take additional, college level courses while completing high school, which would provide them with public school teaching certificates when they graduated.

The excerpt below, taken from a longer article written by a Springview High School historian, offers an in-the-trenches account of life in rural Nebraska during the Depression years. The article also describes the way these hard times affected everyone, including Etta Newland and her fellow students who were enrolled in the Normal Training program.

Springview Normal Training

by Emma Hallock

During the ensuing years more and more young people took advantage of the fine education offered in our high school. The Normal Training Department was one of the best, and students came from South Dakota to get this training so they could teach. Two years of Normal Training and passing the state examinations entitled you to a three-year certificate. Our school graduated 15 to 20 teachers every year. This supplied our county with teachers for many years.

Then came 1929 and the stock market crash. The depression had struck, but it wasn't felt here for a year or two. Then teachers' wages dropped, and farm prices hit a new low. The drought and grasshoppers came, and farmers and ranchers were forced to cut down or sell out. The rural families made many sacrifices to send their children to high school. Since roads were not the best, and cars were expensive, the students had to board in town. Money was scarce so many of them "batched," or worked for their board and room, or rode a horse to school every day. Even then, many dropped out because there just wasn't money enough to pay the book fees and clothe them properly.

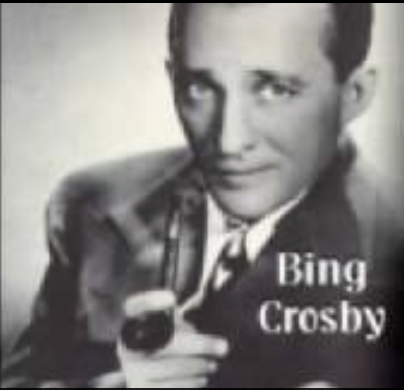

Reflecting the mood of the entire nation in 1932, here’s the number one song from that year:

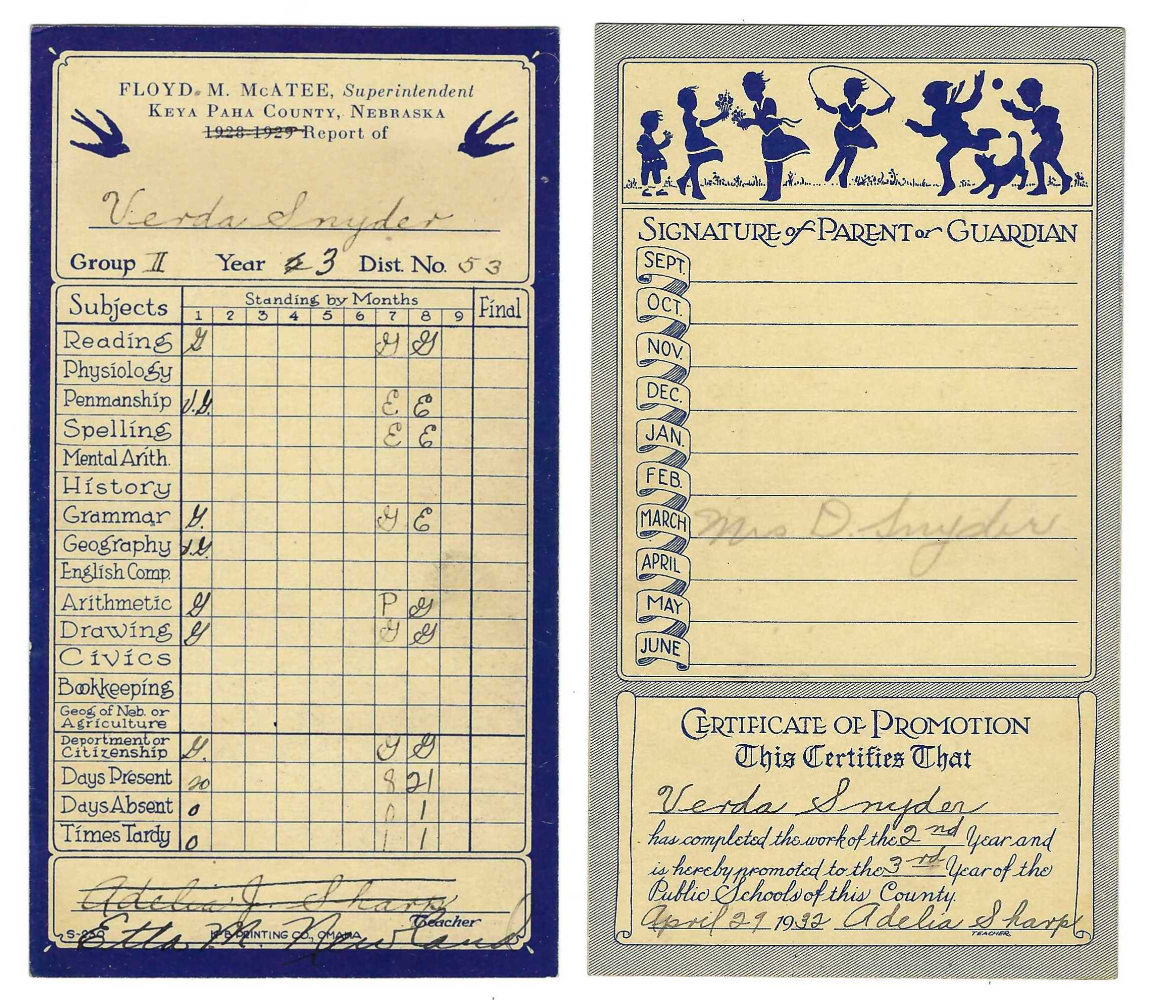

In 1931, Etta Newland graduated from Springfield high school, and with the teaching certificate she received for completing the Normal School Training, she was ready to prepare her students for the future through education. Her high school graduation photo is featured below, and her signature as “teacher” is shown on my mother’s report card from 1932.

With the inclusion of art activities in her teaching, Etta brought a world of beauty to her students when she started teaching in 1932, and the Nature booklet my mother created under her guidance was a true treasure.

My maternal grandmother Fern Conkel Snyder was wise enough to lovingly place the little art booklet into an unmarked cardboard box for safekeeping along with other mementos. And when she left Nebraska for a new life in Washington state in the late 1930s, she took the box with her. After my grandmother’s death, the box was passed on to my mother. I would become the last recipient of the original box when my mother died, and her (unknown to me) Nature booklet inside would finally reach my hands 43 years after it was created.

It was a complete surprise to discover the memorabilia box almost by accident after my mother’s death, under a jumble of shoes on her side of the closet she shared with my father. I tentatively pulled back one of the top flaps of the box, saw the corner of my mother’s high school yearbook inside, and immediately knew that the box most likely contained memories I would have no time to thoughtfully look over during my initial cleaning and organizing. So I placed a “bring to Seattle” note on it and set it aside.

The next day, my father and I loaded his van with a few possessions that were passed on to me—including the memorabilia box—and we headed towards the mountains west from Kennewick, Washington to my home in Seattle.

I wasn’t prepared for the emotional roller coaster that followed the transfer of the box to me. Only a year before, my mother and I had made tentative efforts to reconcile a long emotional estrangement that had started in my early childhood when, as an only child, I learned to keep some distance from a side of her personality that was often unhappy and unpredictably volatile. Although the persona that my mother presented to the outside world was frequently funny, feisty, and industrious, she could also be blunt and outspoken. I would not begin to understand her interior world—the part that stored multiple sorrows and disillusionments—until I was much older. Eventually, I was able to piece together a clearer picture of her history from guarded conversations with relatives combined with a few oblique and cryptic comments that my mother had directly shared with me. Sadly, the information I discovered was far more troubling than hearing about the “health-related” isolation and shame that my mother experienced when she lived in the repurposed chicken house as a child.

After my mother’s death when I was in my mid-twenties, it would be left to me to sort through the scattered pieces of our relationship and reposition them into a more compassionate and balanced view of our time together. I hoped that the contents of her memorabilia box would help activate this new perspective. But I was completely taken by surprise when the insights I was seeking were conveyed to me through an uncanny and synchronistic communication source that seemed to exist outside the familiar boundaries of “normal” everyday conversation. Since then, I’ve actively welcomed and strengthened my access to this alternative form of dialogue.

On the day I arrived back in Seattle, my mother’s unmarked memorabilia box sat in my living room all afternoon while I made some tea and quietly prepared myself for opening it. And when evening arrived, I placed the box on my bed, took a deep breath, and finally pulled back its four top flaps.

Inside, I found an array of mementos from the past that included my mother’s high school yearbook on top. I had to smile as I read the statement she had chosen to accompany her class photo: “Outspoken? Well yes! I guess I am!” As I went further inside the box I found vintage family photos, my own school class photos, and some of my childhood drawings. Since my mother had expressed little interest in my artistic abilities when I was growing up, I felt immensely perplexed knowing that I was now handling her personal collection of my early artwork that she had secretly tucked away for many years.

About halfway through the box, I discovered a small, handbound, paper booklet with cut-out letters on the faded grey cover that spelled the title: Nature. Inside, I saw drawings of birds and flowers, carefully rendered with poor quality crayons on faded, yellowed paper. I didn’t recognize this booklet as anything I had made. But when a vintage-looking printed card fell out from inside as I turned the pages, I saw that it was my mother’s report card from the Nebraska school District, year of 1932. The card was signed by a teacher named “Etta M. Newland.” After some thought, I understood that the young illustrator of the booklet in my hands had been my mother as a child.

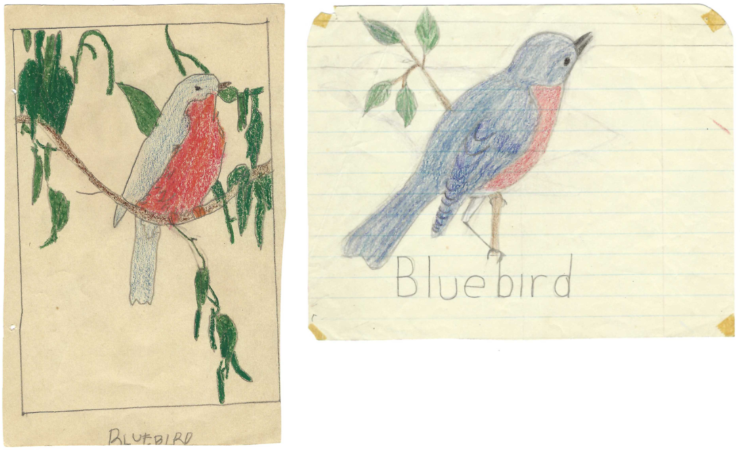

Along with my mother’s report card, three other loose pieces of paper fell out of her Nature booklet. They were forgotten drawings I had made for a 3rd grade school art project of my own, and they illustrated the same three birds—a bluebird, a Baltimore oriole, and a blue jay—that my mother had chosen and drawn for her own 3rd grade school art project in 1932. My mother had never spoken to me about the memorabilia box, or shown me her booklet inside, at any time during my childhood.

The images below show my mother’s 3rd grade bird drawings on the left, and my 3rd grade bird drawings on the right.

After this uncanny revelation of the artistic connection that I unknowingly shared with my mother, I sat for a long time with her booklet in my hands trying to understand its cryptic message inside, encoded in the language of imagery. The only conclusion I arrived at was that my mother’s childhood drawings—part pure and simple nature inspiration, and part psychic oracle for the future—were gifts for me that she was never able to offer in “real” life. Now I was ready to receive them.

But there was one more “alternative” form of communication waiting to arrive that would help me reach a final level of peace in my ongoing inquiry.

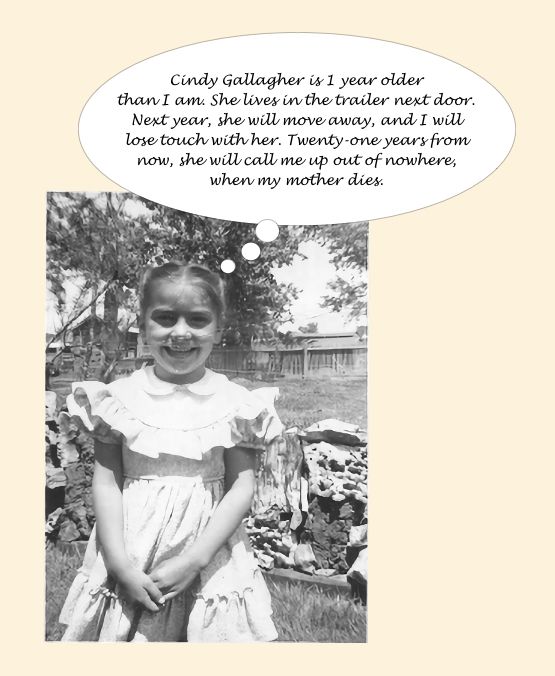

When I set my mother’s booklet aside, I noticed one more loose photo lying at the bottom of her memorabilia box. The photo was of me as a 5-year-old, standing next to a childhood friend named Cindy Gallagher, who lived with her parents in the trailer next to ours. It was Easter Sunday and Cindy and I were dressed in our matching spring finery: pastel organza dresses and fancy hats, with the same little flowered purses in our hands. Cindy was one year older than I and was also an only child. The following year, she and her parents moved away, and since Cindy had often been impatient and short-tempered with me in our childhood interactions, I didn’t feel particularly sad when she left.

As I was holding the photo of Cindy and me together and thinking of my childhood indifference to her “relocation,” the phone rang, and when I picked up the receiver, I could hear the hiss of a (pre-cell phone) long distance call. An unfamiliar voice on the other end said, “Hello, my name is Cindy Gallagher and I’m trying to locate someone I knew long ago in Kennewick, Washington. Her name is Sandra Dean. Is this the right number?” I replied that it was the right number and that, of course I remembered her. I didn’t tell her why.

Twenty-one years had passed since Cindy and I had last seen one another, so I was curious about where she lived and why she was calling me now. She told me that since leaving Kennewick she had been living in Southern California and that about two weeks before, she had experienced a vivid dream about me and my father that was so unsettling that she could not go to work the next day. She sensed that something was wrong and wanted to find out if we were OK. She ended up calling directory assistance and found out that yes, an “Albert Dean” (my father) still lived in Kennewick. She called him, discovered that my mother had passed away, and decided to get in touch with me. When I asked about the time of her dream, I learned that it had taken place the same night my mother died.

Cindy and I discussed the strange synchronicity of her dream and my mother's death. And when I mentioned the surprisingly intense grief and sadness I was feeling about my mother’s passing even though we had shared an extremely difficult history, Cindy told me that she understood completely: she had also felt the same mixed emotions as an only child of a mother whose attention was so occupied with her own unresolved problems that she had little time or energy left to create truly intimate bonds. Cindy hoped that the insights from her own experience would eventually help me review my past relationship with my mother from a clearer and more open-hearted perspective.

After our twenty-one years of separation, there was no trace of impatience remaining in Cindy’s voice. I felt immensely grateful that she had taken the time to follow her dream's prompting. I thanked her for her call, and we jointly put our receivers down. There was no need for further exchange. The important points were made clear through the alternative communication of her dream—and through the artistic revelations I had already received from my mother’s memorabilia box.

Now, many years later, on the mornings when I prepare my art studio for the day’s work, I take out my mother’s childhood booklet from its protective envelope and place it over the tray that holds my pencils and paints. I think about her nature-based drawings inside and realize that through some genetic, DNA-encoded mystery I don’t fully understand, in my own life as a nature-inspired artist, I’ve felt called to use my artistic skills to expand upon and reinterpret some of the same subjects and themes that my mother chose as a child, long before I was born.

When these daily remembrances eventually settle into a calm resting place in my mind, I silently consult with my mother’s invisible presence—as an artistic and collaborative ally.

And then I start my work.

Member discussion