In Search of Tao-chi

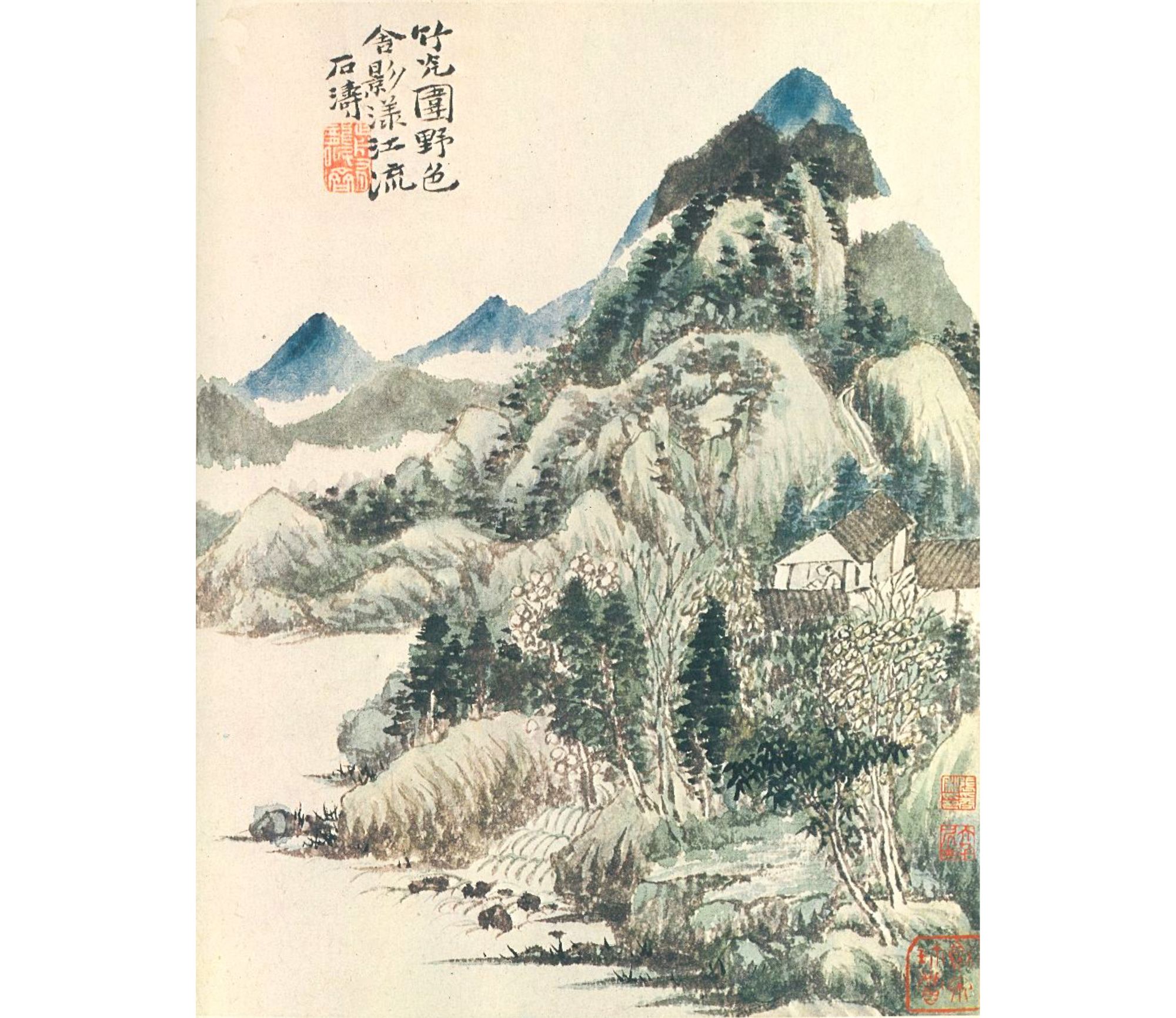

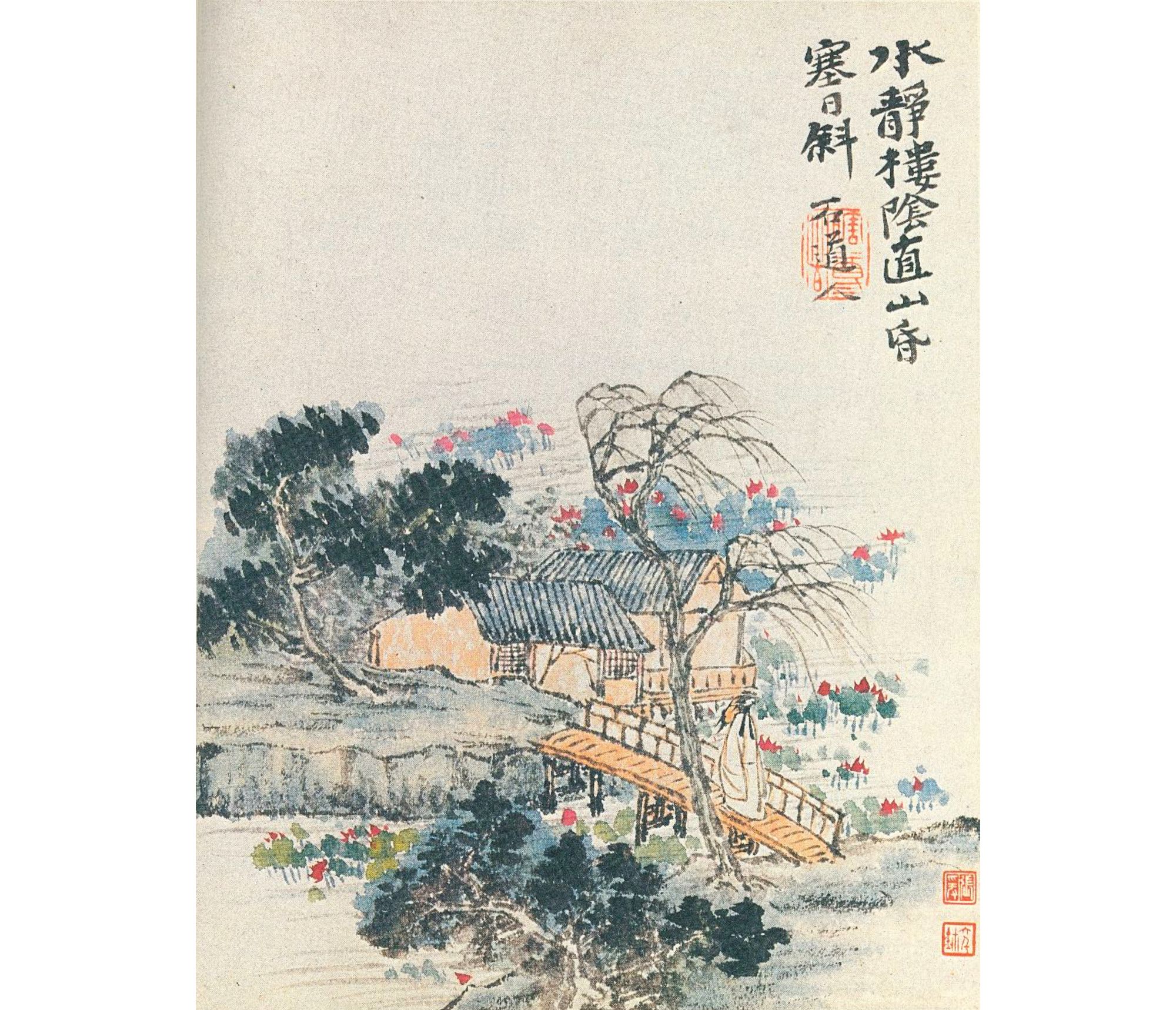

In the mid 1970’s, a friend gave me a treasure of a book that featured several extraordinary color brush paintings and exquisite calligraphy by a 17th century Chinese artist. The book was titled The Wilderness Colors of Tao-chi. I was stunned by the minimalist beauty of Tao-chi’s free-floating paintings and his insightful introductory quote that matched my own nature-inspired views:

Mountains and rivers compel me to speak for them. They are transformed through me, and I am transformed through them. Therefore, I design my paintings according to all the extraordinary peaks which I have sought out. When the spirit of the mountains and rivers meets with my spirit, both their images are transfigured into one.

— Tao-chi, Painter and Calligrapher, 17th Century, China

The Wilderness Colors of Tao-chi portrays his personality as restless, free-spirited, confident, and extraordinarily artistic. In his paintings, calligraphy, and writings, Tao-chi added his own expressions and opinions to an existing body of philosophical and artistic principles that have continually reappeared in Chinese thought over many centuries. I was already familiar with many of these principles from my self-directed studies in Chinese art history, which focused on the interconnected relationships that exist among the artist’s work, the world of nature, and the cosmos—that are often omitted in Western art education.

Tao-chi’s highly individualistic thoughts and work, outlined in his eloquent treatise Notes on Painting expanded my understanding of nature and the artist’s craft in new ways. I felt immediately comforted and at home with the views he presented in his paintings, which combined both spiritual and the practical elements of art making into a unified collection of work:

Tao-chi was born into distant branch of the Ming imperial family in 1641. But when the Ming Dynasty fell to the Manchus in 1644, a family servant helped him find refuge in a Buddhist temple to avoid persecution. Tao-chi eventually became a monk. He initially ascribed to the Zen branch of Buddhism (known in China as Ch’an) and later developed an interest in Taoism. But at heart, he was primarily a painter, valued this gift above all else, and described his personal philosophy directly and without artifice:

I don’t know how to explain Ch’an and I don’t expect alms. I merely sell landscapes done in my leisure time!

— Tao-chi, Painter and Calligrapher, 17th Century, China

In addition to learning more about Tao-chi’s life and artistic philosophy, reading The Wilderness Colors of Tao-chi placed me on a path of artistic pilgrimage to search out his original work wherever I could find it. When I visited London in the late 1970’s, the British Museum’s Asian Art Gallery finally provided me with that opportunity.

When I first encountered several of Tao-chi’s paintings at the Museum, I had no idea that his work would be included in the existing exhibit. So I began my Chinese brush painting exploration by standing before example after example of large, formal, monochromatic paintings of mountains and streams created by Tao-chi’s artistic contemporaries whose work was far more orthodox. Although I could appreciate the predictable mastery of these pieces, I missed the exuberant, colorful, life energy vibrancy I had seen in my Wilderness Colors of Tao-chi book back in Seattle.

After I had paid homage to the work of Tao-chi’s peers at the Museum, I turned to leave the gallery and noticed a dimly lit glass case at one end of the room. It was filled with a magnetic, glowing presence I could feel from afar. And as I approached the case and stood before it, I was elated to discover several small, incredibly lovely, and yes, glowing paintings inside, created by my hero, Tao-chi, the artistic deep thinker whose vision had influenced me so greatly. When I excitedly mentioned the glowing quality of the work to the nearby gallery guard, she replied (with an impatient shrug) that any “illumination” I might be picking up came only from the low voltage light inside the case. I silently smiled and allowed her comment to pass by with no further comment from me.

I stood before the display case for a long time, breathing in the unique, nature-revering, Tao-chi touch that had been missing in the more scholarly paintings on the walls. I silently vowed to someday infuse some of Tao-chi’s artistic vibrancy into any future landscape-based work of my own.

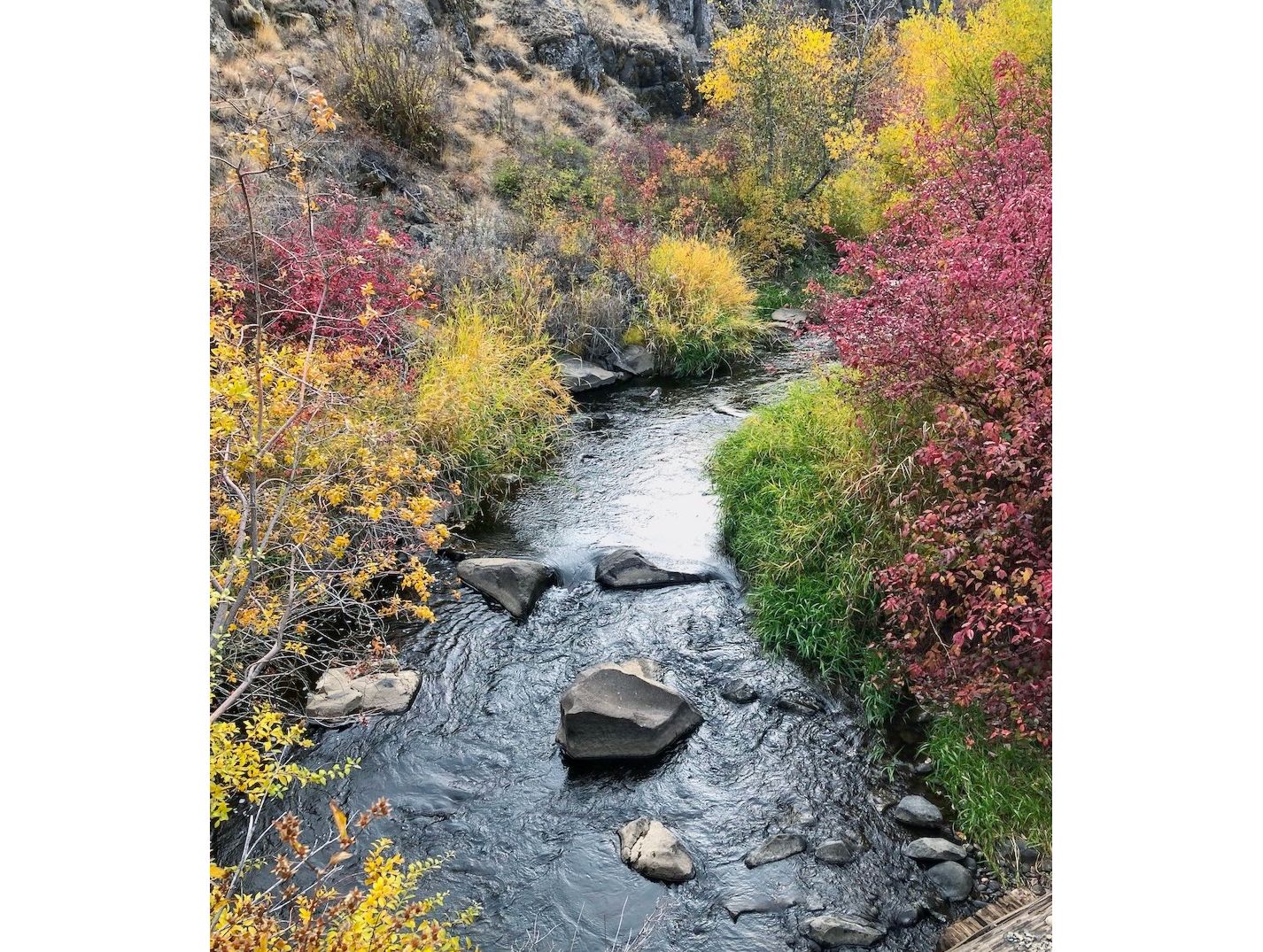

It wasn’t until many years later when I relocated to Central Washington from Seattle, that I realized how strongly Tao-chi’s nature-infused vision had been subliminally imprinted in my mind. Inspired by his wilderness solo wanderings in the unspoiled landscape of southern China, I also began visiting nearby Cowiche Canyon nearly every week for quiet and contemplative walks.

I saw later that the almost abstract renditions of craggy buttes and native plants and foliage that I had created were all quietly pulsing with the sounds of Cowiche Creek and the living spirit of the earth echoing through the valley. I titled these early drawings Voices of Cowiche Canyon. Without thinking about it, I had reinterpreted—in my own style—what Tao-chi himself must have experienced and expressed through his art several centuries earlier.

Since discovering The Wilderness Colors of Tao-chi many years ago, I have set aside time every few weeks to open this treasure book and allow Tao-chi’s nature-based visions to sooth, uplift and transform my artistic spirit— just as they did for him long ago:

Employing brush and ink to write out the myriad things of heaven and earth makes my heart feel joyous.

— Tao-chi, Painter and Calligrapher, 17th Century, China

Member discussion