The Children’s Book Hour

The Early Reader

Stand up and keep your childishness

Read all the pedant’s screeds and strictures

But don’t believe in anything

That can’t be told in colored pictures.

— Ralph Caldecott, British artist and illustrator,

“The father of children’s book illustration” 1846-1886

As an only child growing up without the company of siblings, I drew upon my love of music, art, and reading to keep myself happily occupied in all seasons. I was content with my own company and never abandoned the solitary creative habits I developed for my own joy. Many years later my father told me that he always remembered me “drawing little pictures and singing little songs,” and when not engaged with these comforting pleasures, I played by myself in the open field and orchard behind our trailer. I don’t recall ever feeling bored or lonely.

My early reading menu included illustrated books for young audiences, followed later by the mail-order books I received every month from the Weekly Reader Children’s Book Club. Although I never observed my parents reading books themselves, my father took special note of my talents, and went out of his way to support these interests as time passed. Years later, I learned the reasons for his ongoing generosity and protectiveness towards me. During the Great Depression his mother died suddenly, his birth family completely fell apart, and with no social services available, my father had to leave school before reaching 8th grade. He never forgot these deep disappointments and when he became a father himself, he wanted to make sure that his only child daughter would be able to follow the dreams he had to leave behind.

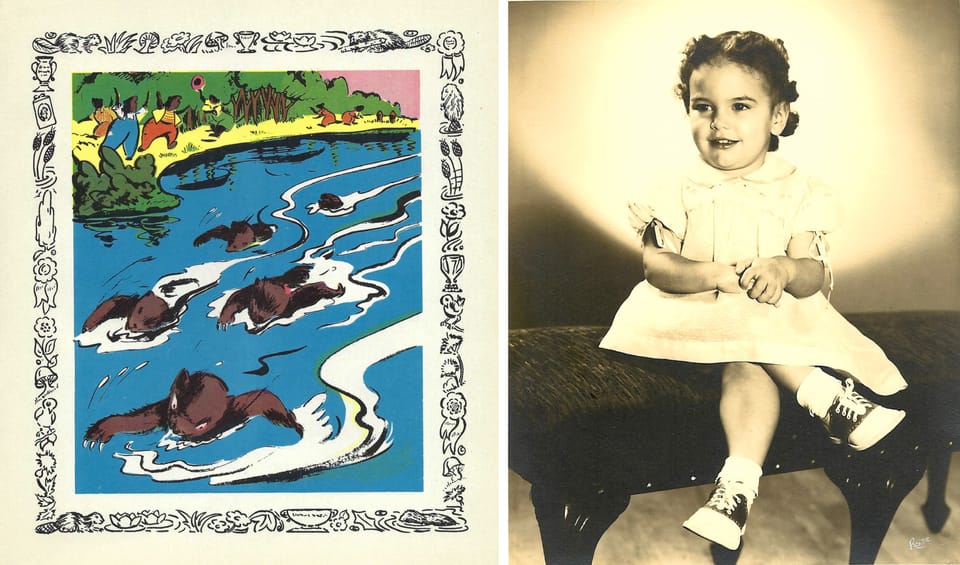

One of the picture books from my very early childhood, titled Bobby Beaver, was particularly memorable, and I loved reading it over and over until I started first grade. Its lively text and color illustrations told the story of “Bobby,” a talented and talkative young beaver who was the best swimmer in Beaver Hollow. He cherished his free-spirited lifestyle and spent most of his time floating on his back singing original rhyming songs, in stark contrast to his more responsible older brothers.

But later, as in many children’s book tales, Bobby had to adjust his priorities. His more complete story (accompanied by educational videos and photos of the active beaver pond only a five-minute walk from my Tieton loft) appears in an earlier Art Nun Journal post titled “My Wildlife Neighbors.” One of the color illustrations from Bobby’s book is shown above as the feature image for this post.

A Surprise Visit

By the early 1960’s my reading abilities had grown exponentially, and I was already searching for more adult level books that could still feed my imagination. Fortunately, new book inspirations soon arrived in my life when a traveling salesman knocked on the door of the tiny house my family had recently moved to on the outskirts of small-town Kennewick, Washington.

The salesman’s visit took place on a Saturday when my parents were home from work, and after welcoming him inside and sharing a few pleasantries, we learned that he was offering what he called a set of “encyclopedias.” Since our house was not located in one of the more affluent neighborhoods closer to town where the “educated people” lived (my father’s term), I could not understand why the salesman would make time to visit us with such a “long shot” offering. How did my parents even hear about the company he worked for?

Although my parents were not book readers, my mother may have seen an advertisement for the encyclopedias in one of the Reader’s Digest magazines that she occasionally purchased, and later contacted the company to schedule a visit from a sales representative. My parents were clearly expecting him, and soon they all sat down to talk over the books’ educational benefits and review the “fine print” of the proposed order. Once everything was clear, my parents wrote a deposit check to reserve our shipment.

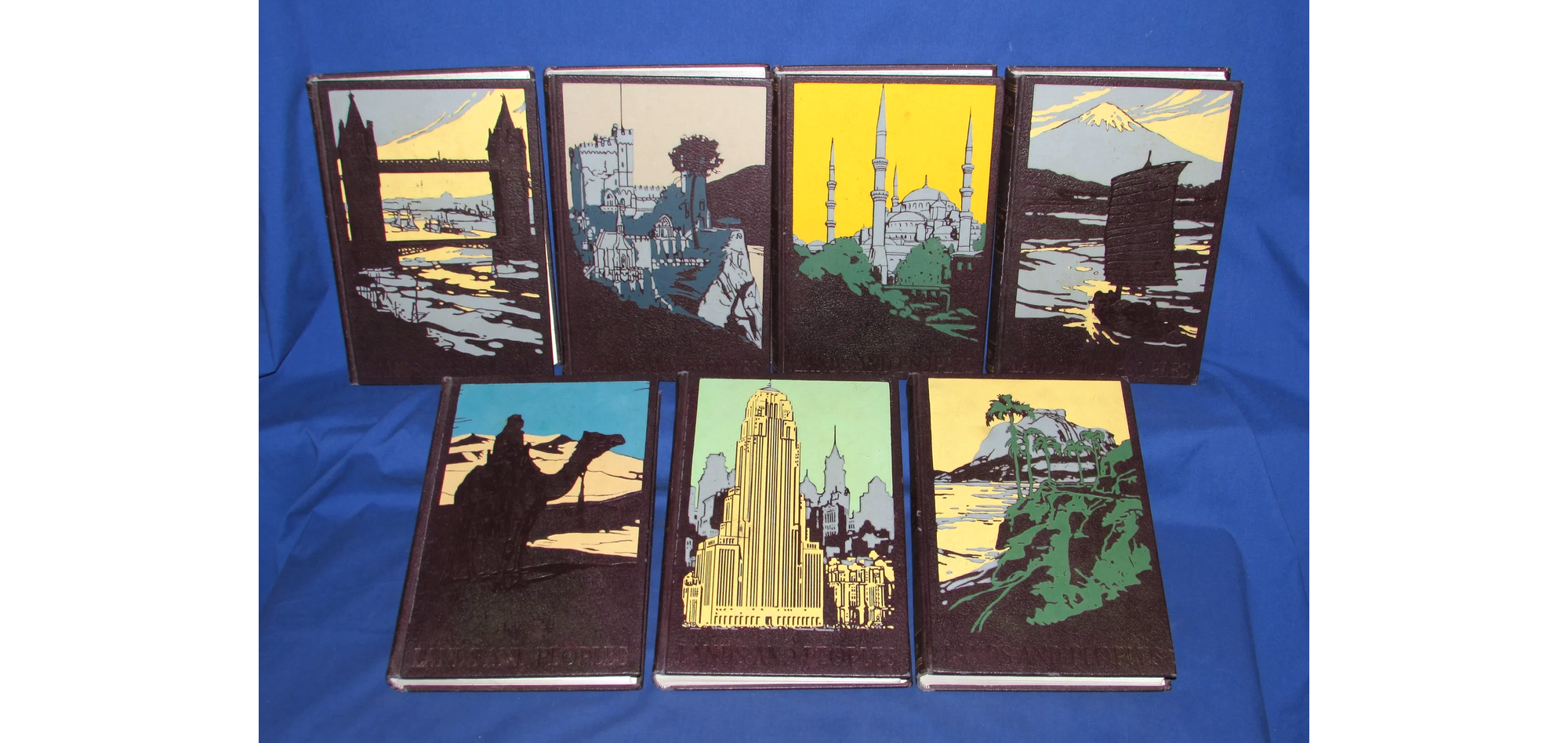

At first, I was not excited by the description of our book purchase as “encyclopedias.” To me the term suggested the yawn-inducing and lifeless books that usually remained unread on the school library shelves. But a few weeks later when a carefully packed box arrived in Kennewick from the “Grolier Society” in New York City, I was happy to discover that my concerns were completely unfounded.

The box contained the advertised collection of seven books titled Lands and Peoples. And instead of the dry and boring academic treatises I had anticipated, the books featured high-quality, well-written articles, accompanied by photographs and maps that described exotic, faraway destinations throughout the world. Best of all, the hand-colored, embossed covers of each book always invited me to explore the contents inside.

These book treasures expanded my existing adolescent fascination with foreign cultures, music and languages. And although the books were meant for adult readers, their artistic touches helped reawaken my earliest memories of reading, which opened new and wider worlds to me when I was a child.

During the weeks and months that followed the book delivery, I spent most of my time reading through every volume in the collection. But it took a few years for me to realize and appreciate that even though my parents had no time for serious reading themselves, they had gone out of their way to purchase Lands and Peoples specifically for me, their artistic, talented, incomprehensible daughter, who was the only reader in the house..

A Brief Introduction to Children’s Picture Books

A picture book combines visual and verbal narratives in a format that is most often aimed at young children, and frequently serves as an educational resource that assists children's language development or understanding of the world. Picture books also fuse text and illustration together to provide more than either can provide alone.

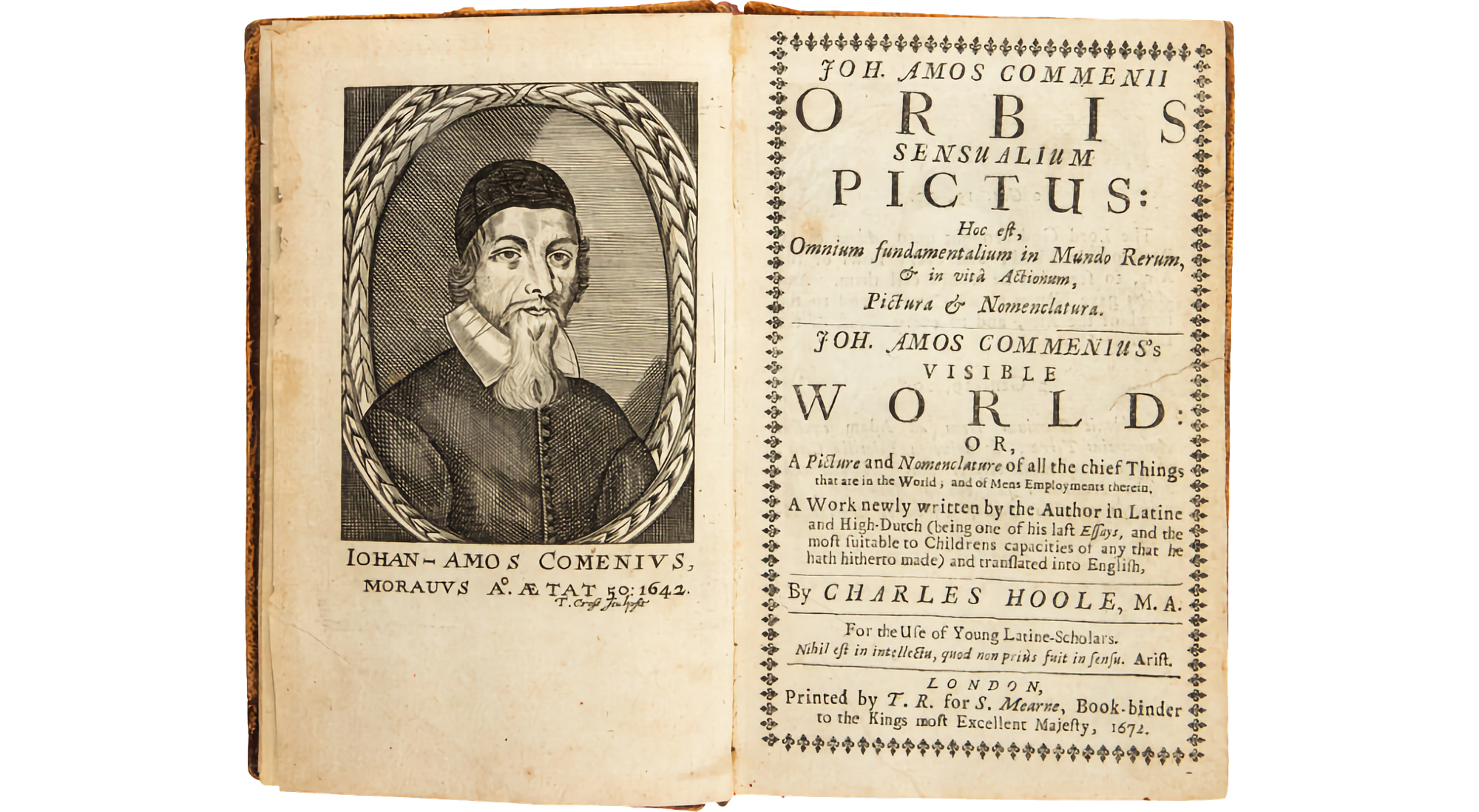

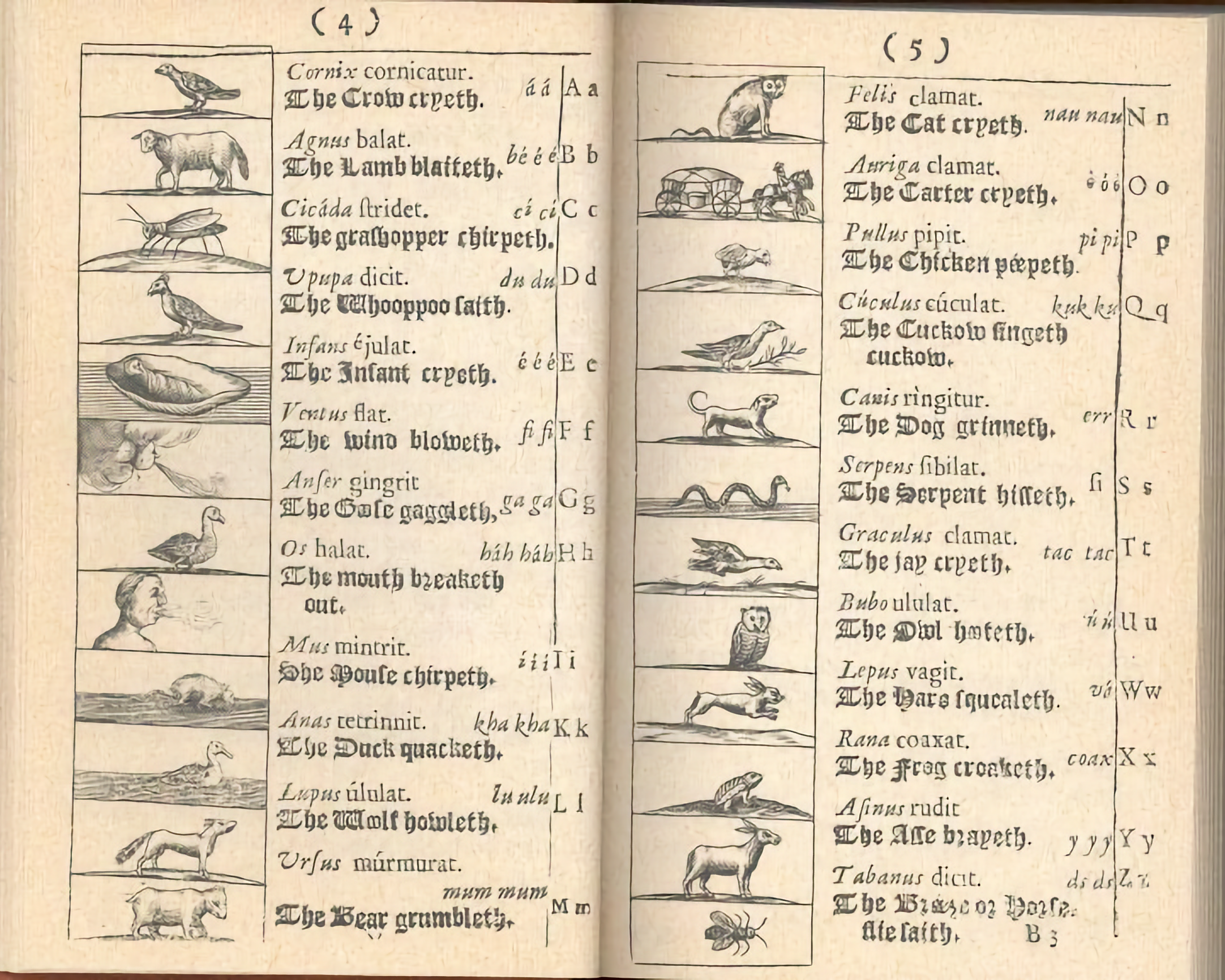

The most famous of early, educational picture books for children was written and illustrated in 1658 by Johan Amos Comenius, a Christian theologian and education reformer who lived in what is now the Czech Republic. In an era in which only wealthy parents could afford to send their children to school, Comenius was an early advocate for providing lifelong, experiential learning for every child, and he promoted teaching methods that went far beyond rote memorization. Instead, he wanted to activate and engage children’s senses. Titled in Latin as “Orbis Sensualium Pictus,” his book was translated to English in 1659 as “The Visible World in Pictures.”

Using his own large woodblock prints as visual aids for the book, Comenius provided children with an introduction to their everyday physical world in just a few hundred pages, which satisfied their natural desire for illustration and example and inspired them to become “wise.”

With the publication of his illustrated book for children, Comenius’ renown as an educational reformer throughout Europe increased. And when his book was translated into several European languages, it became the most respected children’s educational textbook throughout the continent.

Since its first publication in the 17th century, the popularity of Orbis remained stable over the following 200 years, and it continued to be used as a children’s textbook into the early 19th century, both in Europe and in the new land of America.

New Developments for Children’s Picture Books

In the late 19th century, English artist and illustrator Randolph Caldecott (1846-1886) became known as the “father of children’s picture books.” His illustrations, created from colored woodblocks, were unique in capturing the movement, vitality, and humor of the stories they accompanied. Caldecott’s picture books often featured texts taken from traditional nursery rhymes and songs, whose repetitive phrases helped children become more comfortable and engaged with words.

In 1878, Caldecott illustrated two children’s books that became instant favorites: The House that Jack Built and The Diverting History of John Gilpin. Both books were so successful that he made a practice of publishing two children’s picture books every year for the Christmas holidays, and continued this work until his death in 1886.

Two later Caldecott picture books, titled Hey Diddle Diddle and Baby Bunting, published in 1882, were part of his ongoing series of publications, and were based on well-known children’s rhymes.

Medals and Awards for Children’s Picture Books

During the early part of the 20th Century, two awards were created by the American Library Association (ALA) to honor creators of “the most distinguished” American children’s book published the previous year. The first award was the Newbery Medal (1922) which honored the author of the most distinguished children’s book. But since many members of the ALA believed that the artists creating picture books were as deserving of recognition as the authors, a second medal was created in 1937 to honor the most distinguished American illustrator of a children’s picture book. The Caldecott medal was named after the celebrated 19th century illustrator Randolph Caldecott.

My Friend the Library

In the mid 1980s when I still lived in Seattle, I began to collect beautiful children’s picture books after first discovering many of them on the “New Children’s Publications” shelf of my local public library. I visited the library regularly and was always astonished by the variety and high quality of the educational materials they provided: fiction and non-fiction books for all ages, a foreign languages section, services for the blind, and music recordings. As a special treat, the library also hosted free, in-person presentations that authors provided to promote their new books, with friendly book signings afterwards.

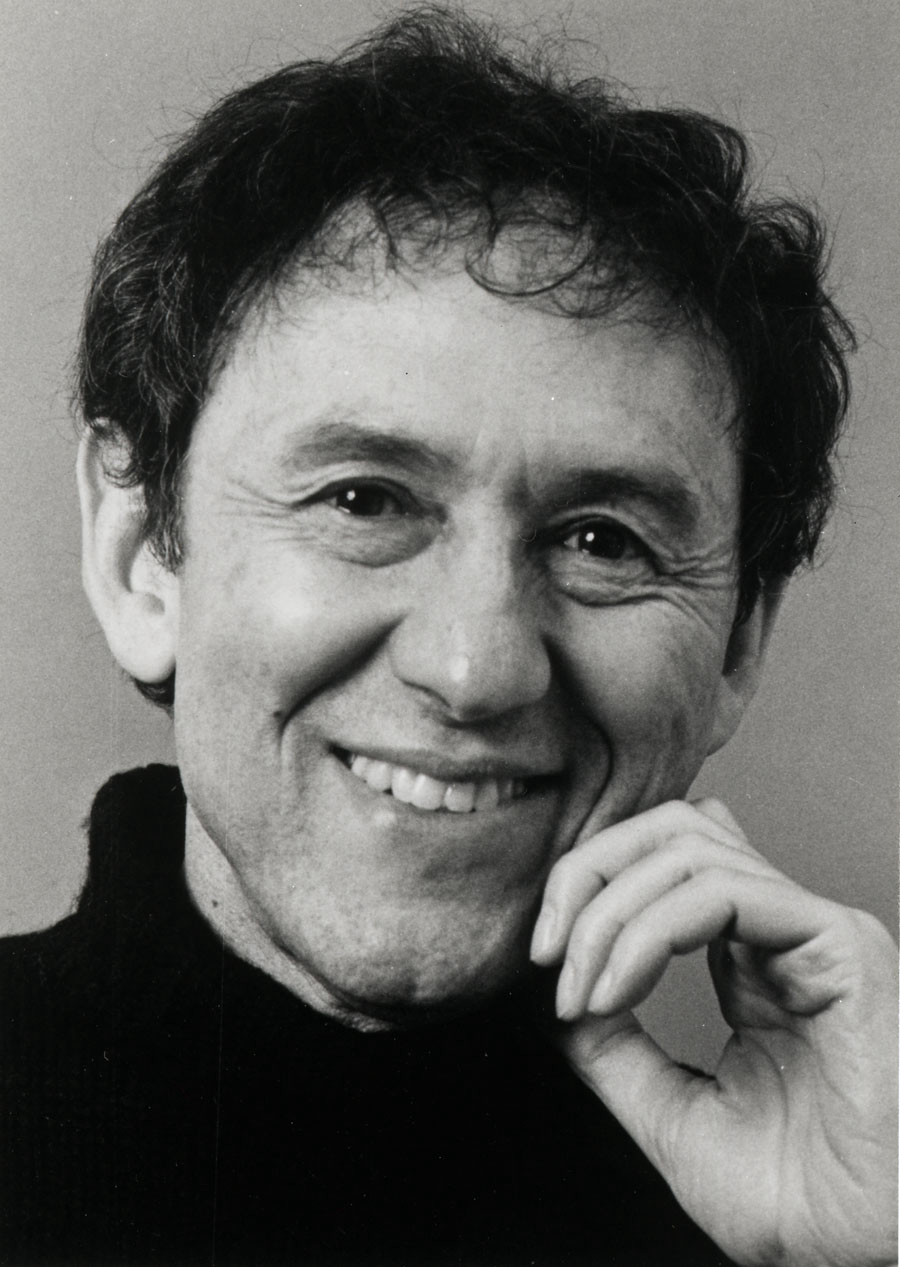

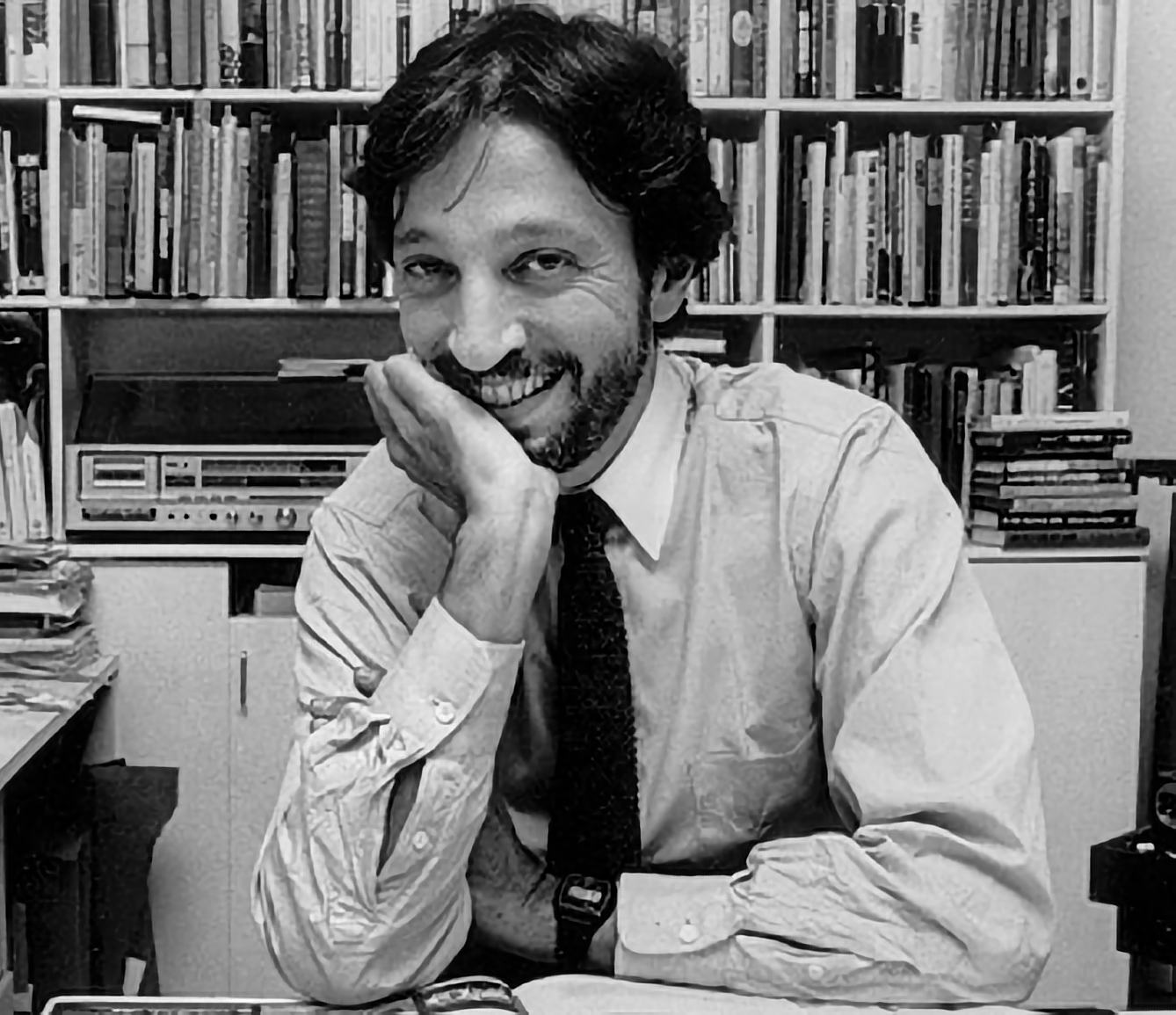

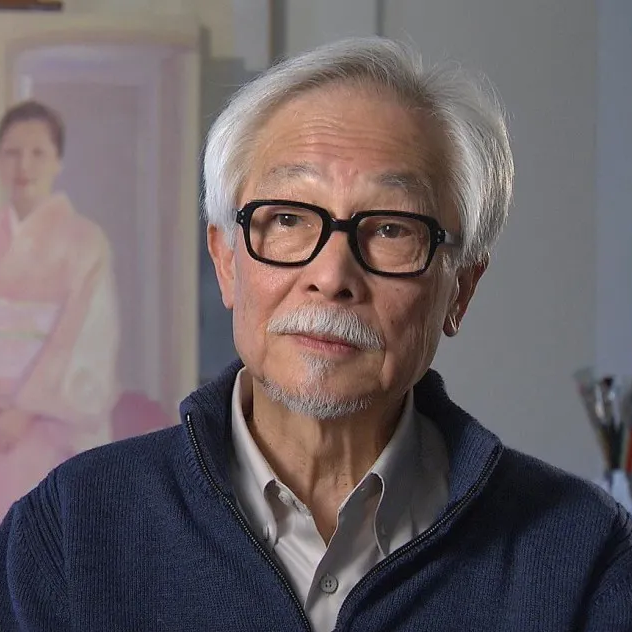

I was fortunate to attend one of these special library presentations in Seattle in 2010, where I met artist Allen Say, the author of Grandfather’s Journey, one of the most poignant and exquisitely illustrated books I include on my list of children’s picture books in the next chapter of this post. We had a lively exchange, then he signed my copy of his book and added a whimsical line drawing of his face.

Here in the small town of Tieton where I now live, our local community library is only a five-minute walk from my Art Nun loft and studio and offers many of the same educational benefits that I received in Seattle, only on a smaller and more personal scale. The librarians are all bilingual in English and Spanish, which is a perk for me, since I am trying to improve my existing Spanish language skills. And if any book is not available within the Yakima Library system, the librarians will initiate a search through the collections of their Interlibrary Loan Service partners throughout Washington state, to have the title sent directly to the Tieton library for pick up. I appreciate that my tax dollars help fund these valuable services, which provide benefits not only for me, but for the ongoing educational health of the larger community as well.

My Children’s Picture Book Favorites

My most beloved children’s picture books are listed below in chronological order by publication year. Many of the books have received either Newbery or Caldecott medals, but all the books are beautiful, thoughtful, and deserving of awe. My own picture book, titled A Tree of Life, was designed for adult readers, but was inspired by the quiet simplicity of children’s picture books.

You can check your local library or independent bookstore for the availability of these books, or search online resources (such as Powell’s, Abe Books, or Amazon).

1927 — Millions of Cats, by Wanda Gág

The enchanting tale of a gentle peasant who went in search of a cat to adopt, but instead returned home with “hundreds, millions, billions, and trillions of cats.” The book was developed from a story that author Wanda Gág had written to entertain the children of friends, and its illustrations and text were designed to look like black and white folk art woodcuts. It was first published in 1928 and is the oldest American picture book still in print. It was eventually published worldwide in 100 different languages and received a Newbery honor book medal.

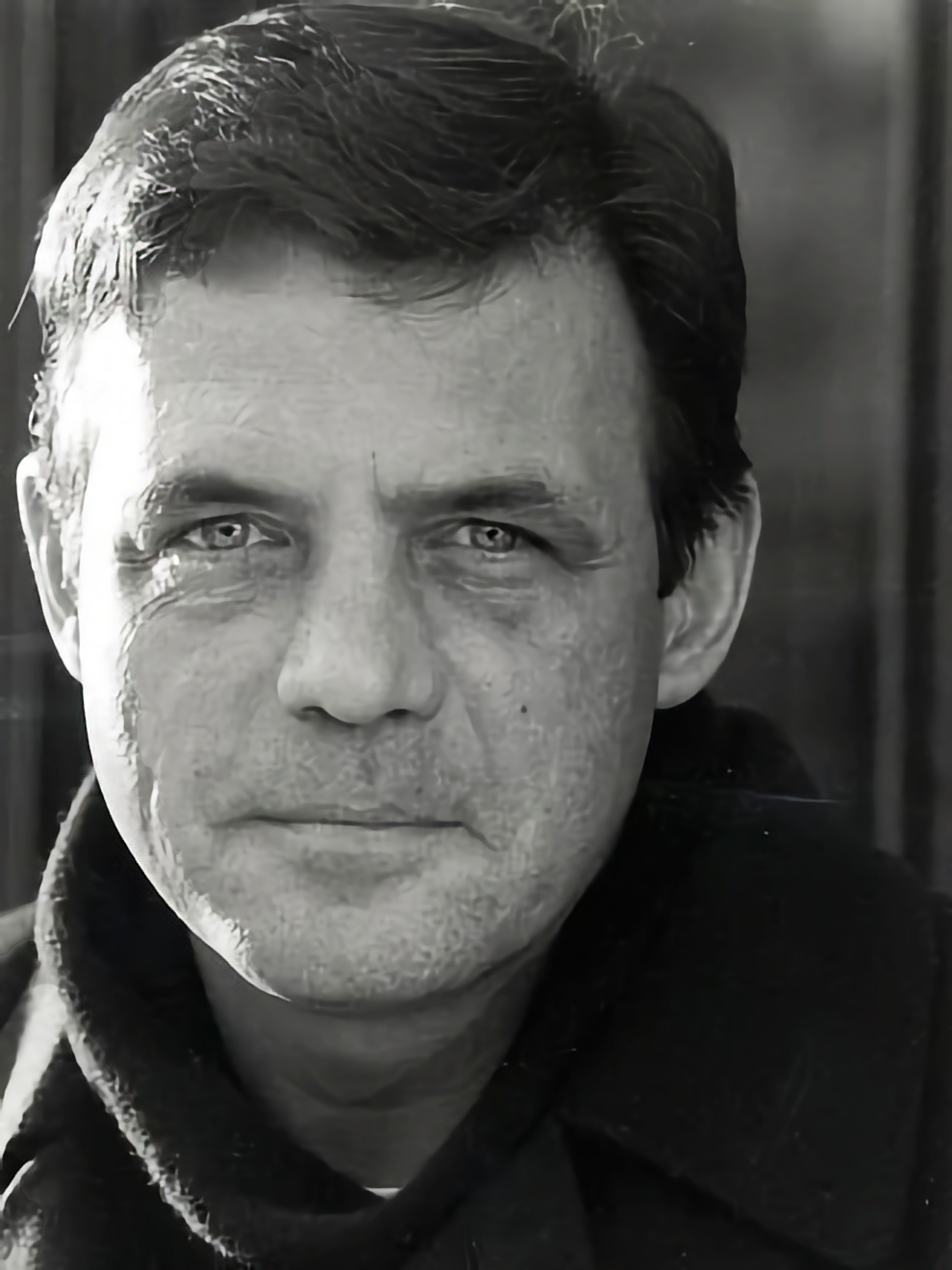

1978 — The Treasure, by Uri Shulevitz

Uri Shulevitz’s full-color illustrations, inspired by the techniques of the “old masters,” offer a fresh interpretation of a familiar story: a poor man experiences a recurring dream that directs him to travel to a faraway city and discover a treasure—only to learn that he must return home to find it. The Treasure won a Caldecott honor medal in 1980.

1990 — Puss in Boots, by Fred Marcellino

The adventures of that rascal Puss and his master, the poor miller’s son, are portrayed in an exuberant series of Marcellino’s sumptuous illustrations that capture both the grandeur and boisterous comedy of the story. A Caldecott Honor Book.

1993 — Grandfather’s Journey, by Allen Say

Through compelling remembrances of his grandfather’s life in both Japan and America, author/illustrator Allen Say offers a poignant account of his family’s unique, cross-cultural experience. Illustrated with exquisite paintings, it is a remarkable picture of the bridging of two cultures. A Caldecott Medal winner.

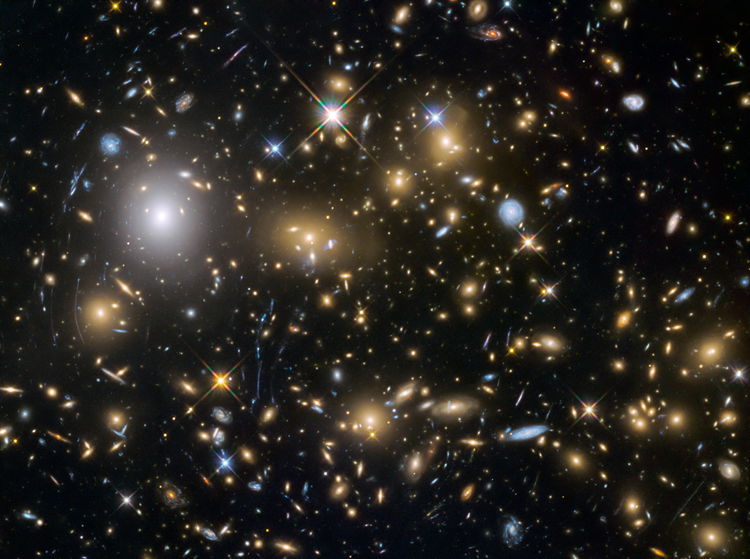

1996 — Starry Messenger, by Peter Sís

Starry Messenger possesses a richness and density that are likely to enchant children and adults alike. Author/illustrator Peter Sís recreates drawings and paintings of uncommon vision that are based on original drawings by Galileo Galilei and narrated in a style of hand lettering that Galileo himself used during his lifetime. The book celebrates the power of freedom of thought, the pleasures of acute observation, and the beauty of a dream held fast by one of the greatest astronomers of all time.

— Elizabeth Spires, New York Times Book Review

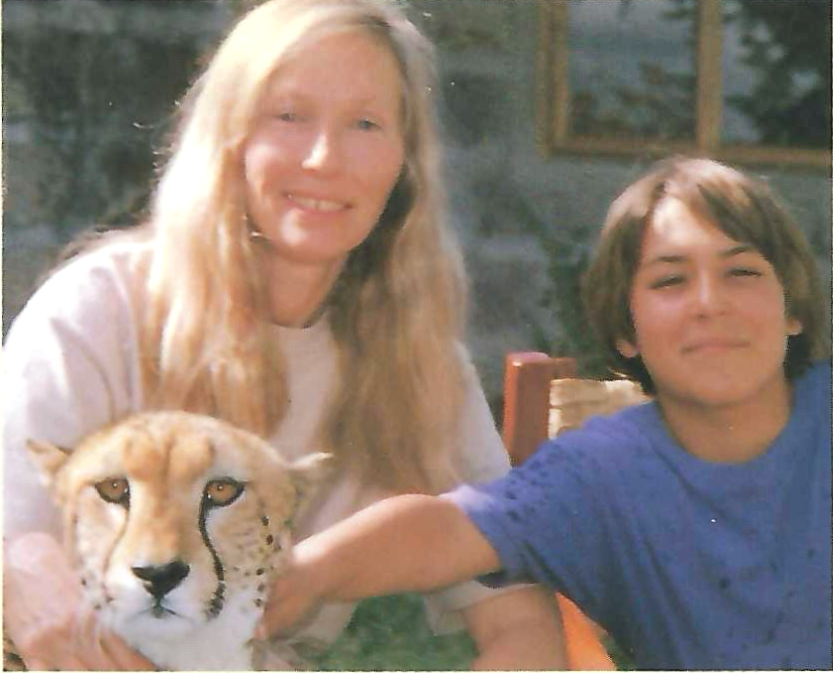

1997 — How it Was with Dooms, story by Xan Hopcraft, transcribed by Carol Cawthra Hopcraft

One afternoon at the game preserve that Xan Hopcraft’s parents managed in Kenya, a visitor arrived with a three-week-old, orphaned cheetah cub tucked inside his coat and asked if anyone would want him. Since the baby was unable to feed or care for himself, Xan’s parents decided to adopt him. They named him “Dooms,” a nickname for a small boy cheetah in Swahili, and over many years the cub became a beloved member of the family. When Xan was seven years old, Dooms died, and his heartbroken human family decided to put together a scrapbook of photos and drawings to ease their sorrow. Xan dictated his memories into a tape recorder and his mother typed the story. The result is How it was with Dooms, a true account of a beautiful animal’s life and his remarkable acceptance of the Hopcrafts.

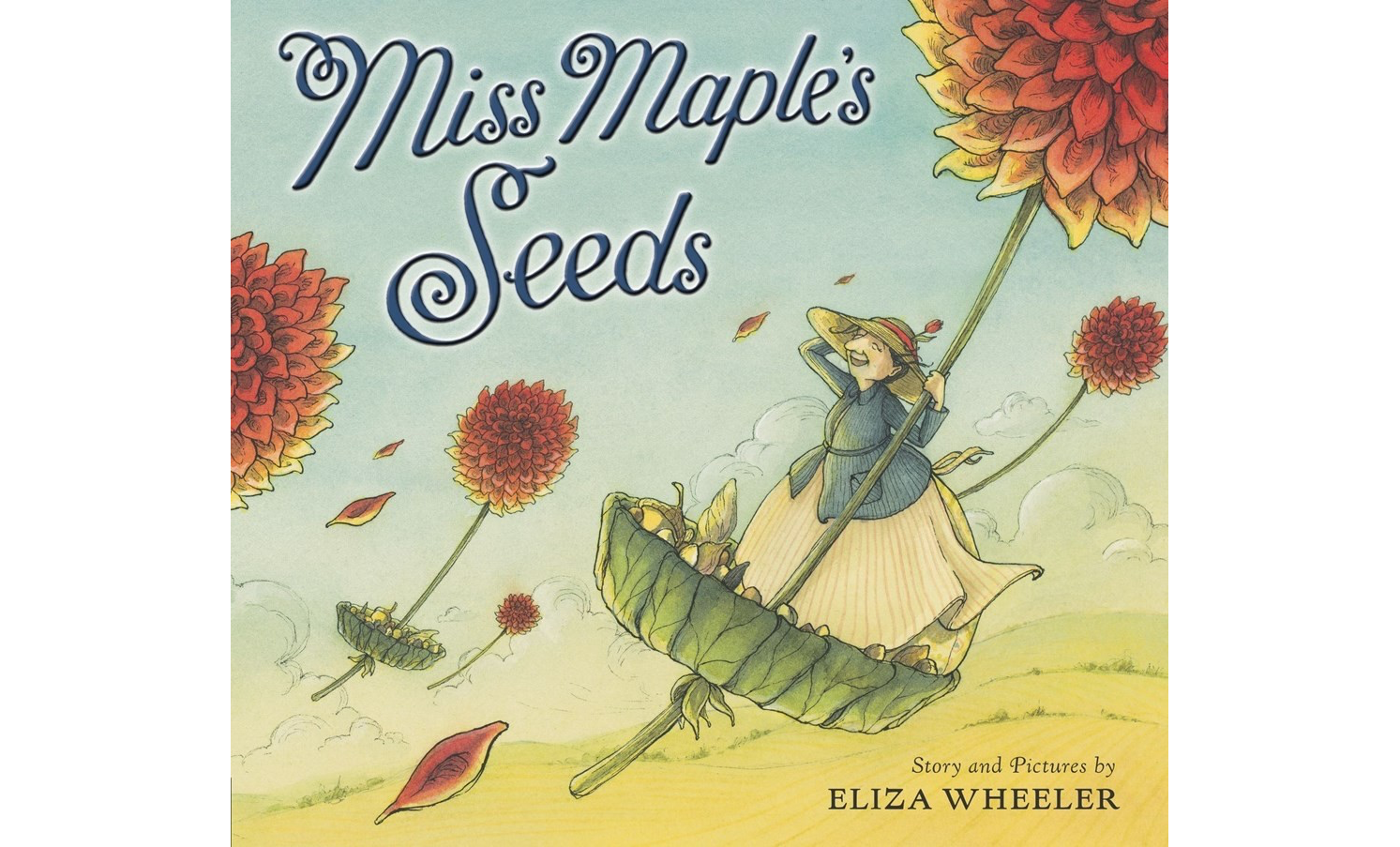

2013 — Miss Maple’s Seeds, by Eliza Wheeler

Miss Maple gathers lost seeds that haven’t found a place to blossom. She takes them on field trips to explore places to grow, and in her cozy, maple tree house, she keeps them safe and warm. In the spring, she sends them off into the wide world to ride the winds and tides and eventually grow roots of their own. Her tender story celebrates the potential inside every seed, since even the grandest tree must grow from the smallest of seeds.

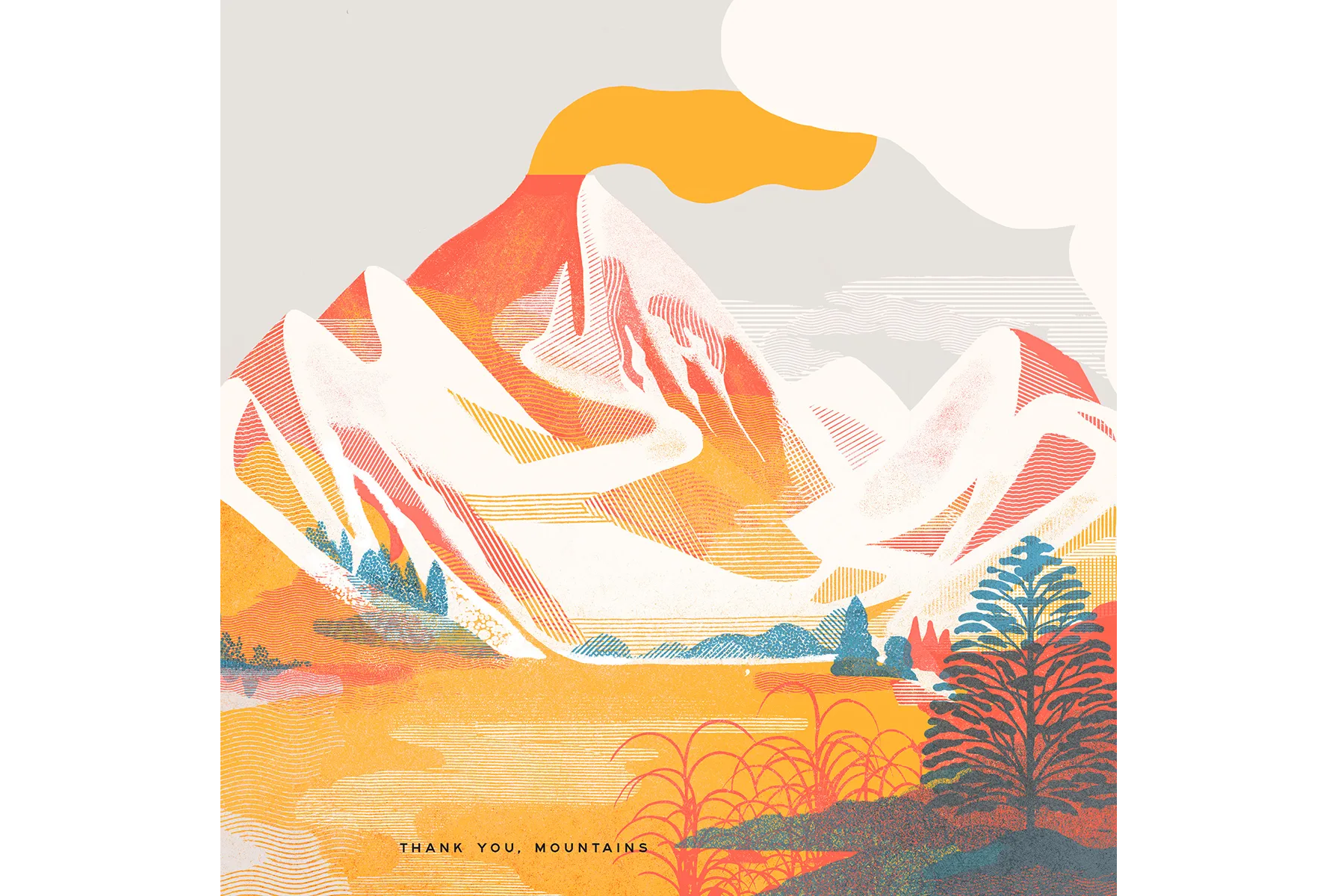

2024 — Thank You, Everything, by Studio Icinori

This original, new, and gloriously illustrated story by Icinori invites readers young and old to linger and reflect on what it means to be grateful for the wonders of our world.

Legacies

— Allen Say, Artist, Illustrator, and Author

— Uri Shulevitz, Artist, Illustrator, and Author

Member discussion