The Shrine at Dodoni

The shrine at Dodoni was the most ancient of Hellenic oracles, and according to 5th century BCE Greek historian Herodotus, its stature and prestige were second only to the famous oracle at Delphi.

Located in a grove of sacred oak trees in a remote, spring-fed valley at the foot of Mt. Tomaros in the region of Epiros, Northwest Greece, the Dodoni shrine and oracle was originally dedicated to an earth goddess known as “Gaia.” And when the first sanctuary was established in her honor between 1750 and 1050 BCE, traveling pilgrims began arriving from most of the Greek world and its colonies to seek guidance from the resident priestesses and priests who presided there.

In the writings that describe his travels throughout the Levant and Egypt (also during the 5th century BCE), Herodotus mentions the long tradition of prophetic divination that existed in the pagan world and cites a legend that had been relayed over centuries by priests at a temple in Egypt. The story tells of two sister priestesses who had practiced divination at an Egyptian temple in Thebes but were captured by seagoing Phoenician traders and later sold as slaves.

Both sisters never forgot their previous high stature as prophetic seeresses and brought these skills with them to their new (unintended) homelands. One of the sisters was sold near the Oasis of Siwa (in present day Libya) and later became a respected attendant at a shrine in that location. The other sister was sold on the northwest coast of “Hellas” (the ancient name of Greece) and eventually became one of the first priestesses to preside at the shrine of Dodoni that was established further inland in the valley beneath Mt. Tomaros.

The Dodoni shrine was not only a center of power and religious activity in ancient times but served as an important focal point of economic and political life on the entire Greek mainland. Unfortunately, the increasing religious intolerance that arose throughout Greek society at the beginning the 3rd century CE soon began to threaten the delicate balance of Dodoni’s spiritual future, and as more time passed, Dodoni arrived at a dangerous and irreversible tipping point.

My First Trip to Greece

The abbreviated introduction to Dodoni’s history that begins this post was completely unknown to me when I first traveled through Greece in 1984, after taking an introductory Greek language course at a Greek Orthodox church in Seattle.

For some unknown reason, since childhood I have always been fascinated by “foreign” cultures, foods, languages, music, and customs, and as I grew older, these interests multiplied exponentially. I realized much later that the weathered copy of a 1940’s National Geographic book I had purchased at a yard sale in high school had likely fueled my ongoing fascination even more. Illustrated in detail by an accomplished artist, the book was titled Everyday Life in Ancient Times: Highlights of the Beginnings of Western Civilization in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

The book’s style reflected a patriarchal and militaristic focus that was common in 1940’s era academic writings, in which accounts of priestesses and shrines were only minimally included in the contents. It would take several years of concentrated research, study, and travel on my part—combined with an unusual directive I received from a wise Greek mentor much later—for the details of Dodoni’s fascinating story to eventually unfold for me in real life.

An Unexpected Meeting

On my first trip to Greece in 1984, I was fortunate that a Greek friend in Athens who knew I was a nature-influenced artist—decided that I should meet a respected public figure in Greece named Niki Goulandris—a botanical painter, a speaker of four languages, a generous philanthropist who supported environmental causes, and the co-founder (together with her husband Angelos) of the Goulandris Natural History Museum in Athens. My friend made a call to the museum to provide some background about me and surprisingly, she soon received a call back from the museum’s staff saying that Ms. Goulandris could meet with me at her office that same week.

As an unknown outsider I initially felt extremely hesitant as the meeting day approached, but when I arrived at the museum and shared some (pre-computer age) photos of my artwork with Ms. Goulandris, I discovered that we enjoyed many complementary views and interests. She understood immediately that I had not traveled to Greece to seek out the “best tourist beaches” and proceeded to graciously exhibit to me the important Greek concept known as “Philoxenia” (love for the stranger) as she freely shared her knowledge of beautiful and quiet destinations in Greece that would be a perfect fit for an artist like me.

After our meeting, I thanked Ms. Goulandris for her generous recommendations and spent the rest of the afternoon exploring the exhibits at the museum and learning more about its history and programs.

I had no idea at the time that this 1984 introductory meeting would be a precursor to a more revelatory conversation with Ms. Goulandris years into the future.

The Goulandris Natural History Museum

The Goulandris Natural History Museum (whose entrance is shown in the photo above) was one of the first public institutions in Greece to foresee the negative repercussions of humanity’s mistreatment of nature, long before the term “climate change” became well known. Since its founding in 1964, its collections, exhibits, publications, and tireless dedication to the cause of environmental education have collectively generated a greater respect for the earth’s intricate and interconnected ecosystems, especially among the thousands of school children that the museum has enthusiastically welcomed over many years.

Niki Goulandris’ role in the Natural History Museum’s early years was unique. She was not only an inspiring public spokesperson for the museum’s ecological vision since its founding, but also worked behind the scenes to create nearly all the illustrations for the botanical research publications that the Museum supported, which document the extraordinary wealth of native flora that exists throughout Greece.

An example of Ms. Goulandris’ artistry is shown on the 1984 cover of the botanical research publication below. The English translation of the original title in Greek reads: Peonies of Greece: A Taxonomic and Historical Survey of the Genus Paeonia, by William T. Stearn and Peter H. Davis.

Before Niki Goulandris and I parted after my unplanned visit with her in 1984, we both spoke of meeting again sometime in the future. But unfortunately, the business of everyday “life” intervened as time passed, and we were not able to meet again in Greece until nearly twenty years later.

By then, new directions were being planned for the Goulandris Natural History Museum.

For years, Angelos and Niki Goulandris had discussed the idea of creating a branch of the Natural History Museum that would incorporate the latest developments in digital technology to present environmental education in an innovative and more contemporary setting. The new building would be connected to the existing museum on an adjacent property. In the early 1990s, the Goulandris's began collaborating with an international team of museum specialists, Greek government agencies, representatives from the EU, and additional enthusiastic supporters who shared their vision: to transform the proposed museum into reality as a tribute to Angelos Goulandris’ values and life mission.

Unfortunately, in 1996, Angelos Goulandris passed away, and four years would pass before the new museum would be completed. In 2001, it finally opened its doors as the first museum of its kind in Greece, and carried a name that Angelos Goulandris himself had chosen before his death: the Gaia Center for Environmental Research and Education, (shortened as “the Gaia Center”) which honored the original earth goddess that had reigned at the ancient shrine of Dodoni.

Together with Nature at the Gaia Center

The new educational facilities at the Gaia Center attracted scores of first-time visitors, who were inspired by the immersive and interactive displays that brought the earth’s life and challenges into sharper focus.

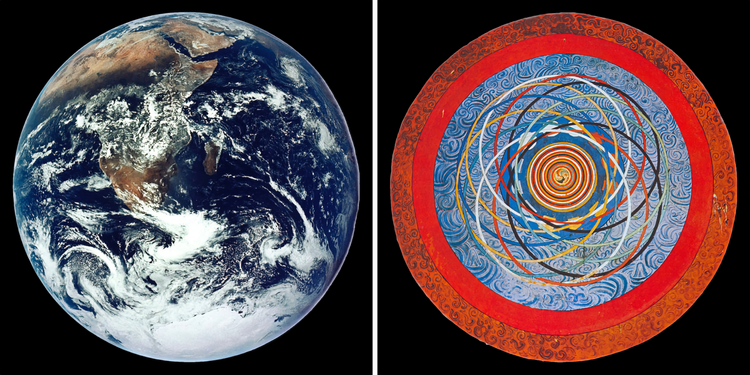

The spectacular Geosphere inside the Gaia Center is unique in the world. It consists of a hemispherical dome-monitor that shows the rotating planet in 225,000 high resolution images. It also presents the geological evolution of planet earth from its creation 4.6 billion years ago until today.

An Unusual Directive from Niki Goulandris

In 2004, I arrived in Athens for the second time with two goals in mind—to follow through with the proposed reunion with Niki Goulandris that we had both talked about twenty years before, and to explore the new Gaia Center that I had read about before I arrived.

I was not sure that Ms. Goulandris would remember me at all from our one-time conversation in 1984, so on my visit to the new Gaia Center I brought a book of my nature-inspired drawings as a gift for her that might help identify me. As I explained this situation in Greek to the receptionist and showed her my book, she picked it up, smiled, and disappeared for a short time. She soon returned to graciously escort me into Niki Goulandris’ onsite office.

Niki Goulandris had indeed remembered me, and we spent the next hour talking about her work, my work, her new role as president of both museums after her husband’s death in 1996, and my enthusiasm for seeking out higher level Greek language studies. During my first visit with her in 1984, she had graciously offered me several recommendations for destinations I would enjoy on my travels in Greece. When I asked the same question again in 2004, she looked at me intently, was silent for a few moments, and then replied:

“You must go to Dodoni, because that is where the real communication is taking place.”

The City of Ioannina and Dodoni’s Early History

“Dodoni” was an unknown destination for me, and it was clear in 2004 that it would take further Greek language studies to get my speaking skills fluent enough to easily travel there. My husband David and I had already started immersive Greek language classes on a small island in the eastern Aegean and decided to continue higher level studies at the same school over the next two summers. My exploration of Dodoni would have to wait until we returned to Athens in 2006, with our improved Greek language skills ready to be exercised.

The following week, we took a bus to the city of Ioannina, in the northwest corner of Greece, about a half hour drive to the shrine of Dodoni. I spent my first days in Ioannina searching through local bookstores, where I bought several books that helped bring the story of Dodoni to life.

Towards the end of August, 2006, I finally arrived at the ancient shrine and felt instantly comforted realizing that I was the only visitor at the site. I savored the delicious solitude, closed my eyes, listened to the constant birdsong and rhythmic hum of insects, and allowed my own intuitive receptivity to summon the real communication with the earth that was taking place all around me, just as Niki Goulandris had described to me so clearly in her office a few years before.

The following series of drawings—based on archeological excavations and ancient texts cited in one of the books I bought in Ioannina—were created by 20th century illustrator B. Harisis. His work documents the evolution of the first (quite humble) shrine at Dodoni as its design became more elaborate over time:

In c. 290 BCE, Greek King Pyrrhus made Dodoni the religious capital of his domain and implemented a series of grand construction projects that included a large amphitheater where musical and dramatic performances were presented, and additional outdoor facilities that were used for athletic games and contests.

The attendants at the shrine of Dodoni had the responsibility of interpreting the oracle, and the ancient Greek texts made extensive references to details of the religious practices that were associated with this honor. According to Homer, the priestesses and priests always went barefoot and slept on the ground beneath the sacred tree to be in more direct contact with the earth herself, whose invisible presence strengthened their own intuitive and prophetic abilities.

Throughout the prehistoric period and until the end of the 5th century BCE, worship at Dodoni was always conducted outdoors around the sacred oak tree—a living power totem that visibly embodied the earth spirit that was thought to reside in its roots. In response to specific inquiries from pilgrims, the shrine’s religious attendants first attuned themselves to the inner intelligence of earth that coursed upwards through the roots of the sacred oak tree and then formulated prophetic responses based on the rustling sounds of its leaves.

This spiritual practice was not to last. In 290 CE, Christian emperor Theodosius shut down all pagan sites, banned all existing pagan religious activities, and decreed that future ceremonies would also be forbidden. Almost immediately, unrestrained bands of religious zealots began to attack, burn, and demolish unprotected sanctuaries, and as a final blow to Dodoni itself, the marauders cut the ancient, sacred oak tree to the ground.

The sound file below features a section of an instrumental (violin) lament (called “Mirologi”) from the region of Epiros in NW Greece where the shrine of Dodoni is located. The lament is taken from the original recording made in the 1920’s, that to me reflects some of the anguish and sorrow associated with benign Dodoni’s fate.

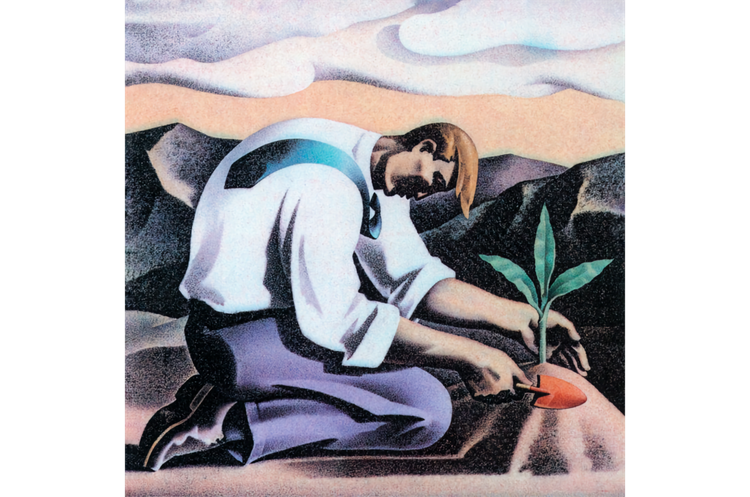

In the early 1950’s, a Greek archeology professor named Sotiris Damaris gathered with students and assistants at the shrine of Dodoni to plant a young oak tree in the same location where the sacred tree had stood for centuries. He believed that replanting the tree would help recreate the ancient environment of Dodoni, and provide modern day visitors with a more accurate idea of the shrine’s original setting.

As a privileged pilgrim to the shrine of Dodoni much later, I walked the same paths and stairways that priestesses and priests followed in ancient times. I removed my shoes and stretched out on the same green earth that they loved, and listened to the same rustling of leaves that they heard.

Thanks to the wise words of direction I received from Niki Goulandris in 2004 and my own explorations and experiences since then, I now understand that the ancient voice of the earth—which coursed through the tree’s roots long ago—is alive and still speaking today.

“You must go to Dodoni, because that is where the real communication is taking place.”

— Niki Goulandris, 1925-2019

Member discussion