Visionary Voices

In 1975, I bought a small, 1918 cottage on the lower west side of Queen Anne hill in Seattle because it was quiet, had room for a garden in the backyard, and was set back from the street next to a tree covered hillside to the north. Racoons and possums were my neighbors. It was the last house on the street and the perfect spot for a visual artist like me to begin creating a private, urban oasis.

I started exploring my new neighborhood every week, especially the more expensive houses and gardens further up the hillside that had magnificent views of the Olympic mountains beyond Puget Sound. My usual walking route took me to an almost hidden City stairway that eventually arrived in front of what became my favorite Queen Anne house. It was quiet, elegant, and subtly Asian in its aesthetic, with a tiny front garden entry of native ferns, azaleas, hostas, and white roses. I could see through the leaded glass front windows to gorgeous paintings on the walls and mountains on the western “view” side.

I always stopped for several minutes on the stair landing as I approached the house, to listen to the sound of falling water from the fountain just inside, and wondered who the fortunate owners were of this mysterious, “gem of a home.”

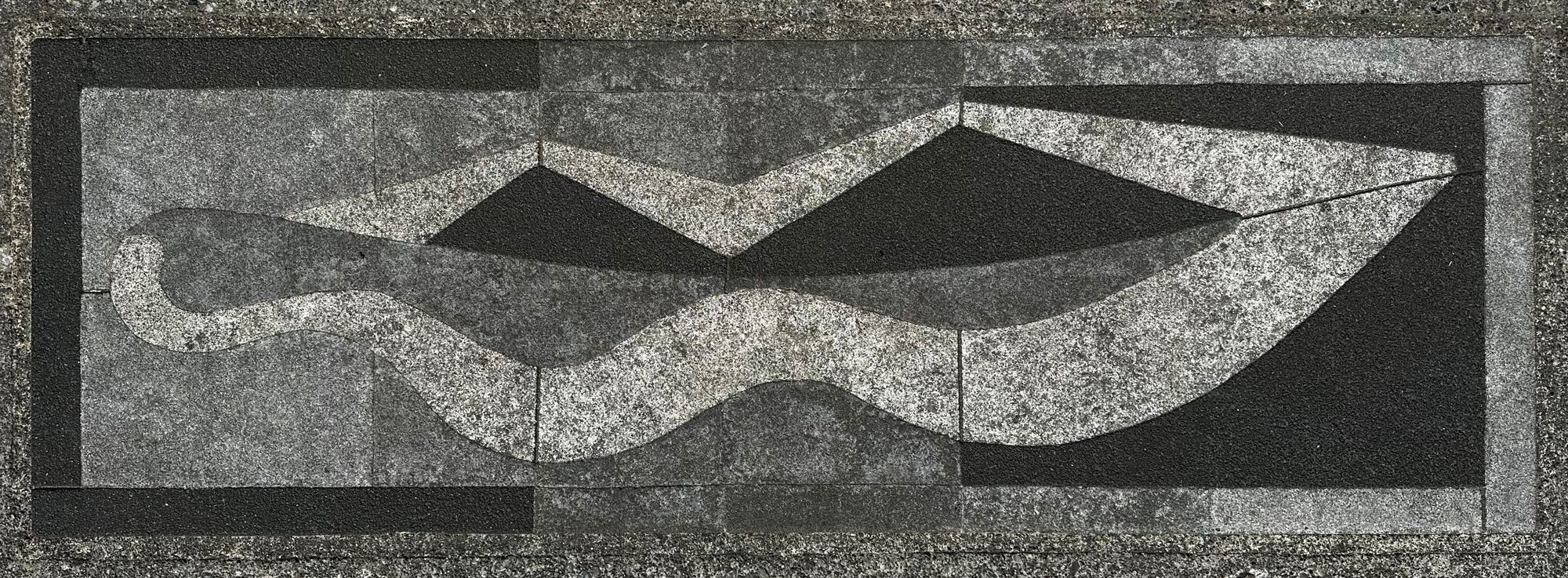

As a visual artist, I always enjoy seeking out public and private art in a variety of settings, and on my walks past the mysterious house nearly every week in the mid-1970’s, I also stopped at one of Queen Anne’s small pocket parks about a block further up the hill, which featured a lovely viewpoint that looked out over the Olympic mountains. It was a favorite sunset setting. I noticed construction at this viewpoint in 1978, and learned later that a series of large, enigmatic, cast concrete art panels would be installed into the city walkway as memorials to a well-known Seattle art patron named Betty Bowen. She had been a staunch advocate of the artists whose work would appear at the viewpoint, and her friends had established an artist grant in her name after her death.

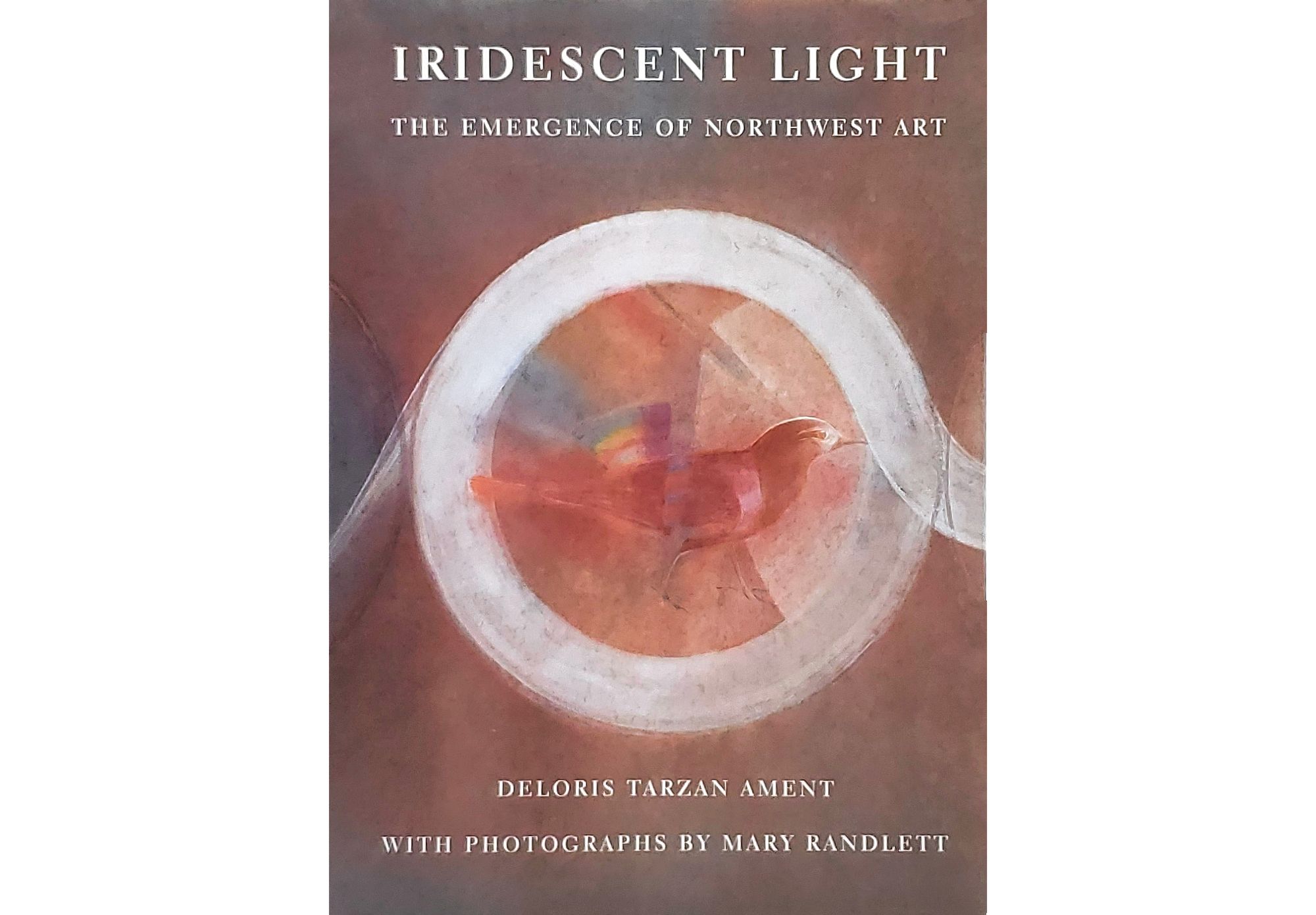

In 2002, still completely unaware of who had created the concrete panels at Betty Bowen Viewpoint, I purchased art critic Dolores Tarzan Ament’s book, Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art.

I loved reading details about the lives and artwork of so many of the “Northwest Visionary” artists whose work I had long admired. Like me, many of these artists had also been drawn to explore and visually document what they referred to as “the Mysteries”— the blended influences from Asian arts and philosophies that were reflected in the visual poetry of their work.

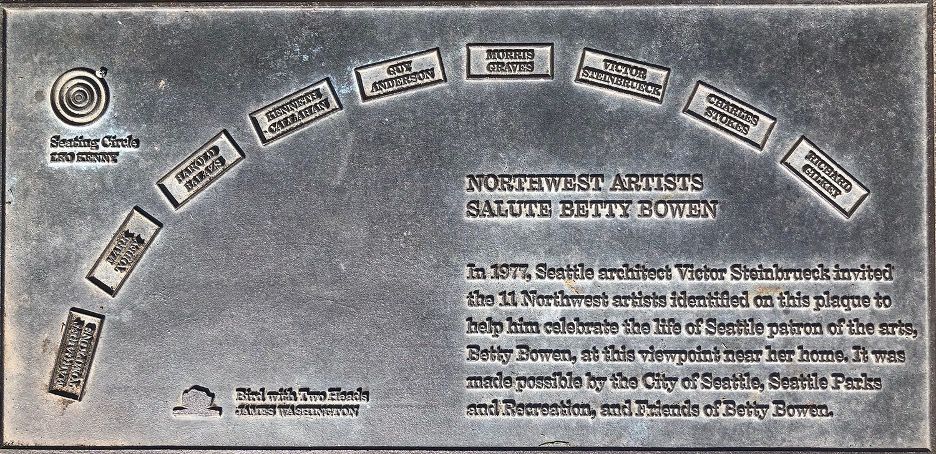

On my next walk to Betty Bowen Viewpoint after reading Ms. Ament’s book, I discovered a small, explanatory plaque on the eastern side of the concrete installations that listed the names of the artists whose work appeared there. I was stunned to realize that for many years I had been living only a few blocks away from real artwork created by many of my Northwest art heroes.

The artists included (in arc, left to right): Margaret Tomkins, Mark Tobey, Harold Balazs, Kenneth Callahan, Guy Anderson, Morris Graves, Victor Steinbrueck, Charles Stokes, Richard Gilkey, (either side of arc) Leo Kenney and James Washington Jr.

In 2003, 2004, and 2005, I worked with a small group of artists and poets to create a unique public arts event called the Queen Anne Treewalk. It was a free, one-day, collaborative, self-guided walking tour through several West Queen Anne parks, with site-specific art and poetry installations along the route. The event was sponsored by the City of Seattle Department of Parks and Recreation and additional public funders and private donors.

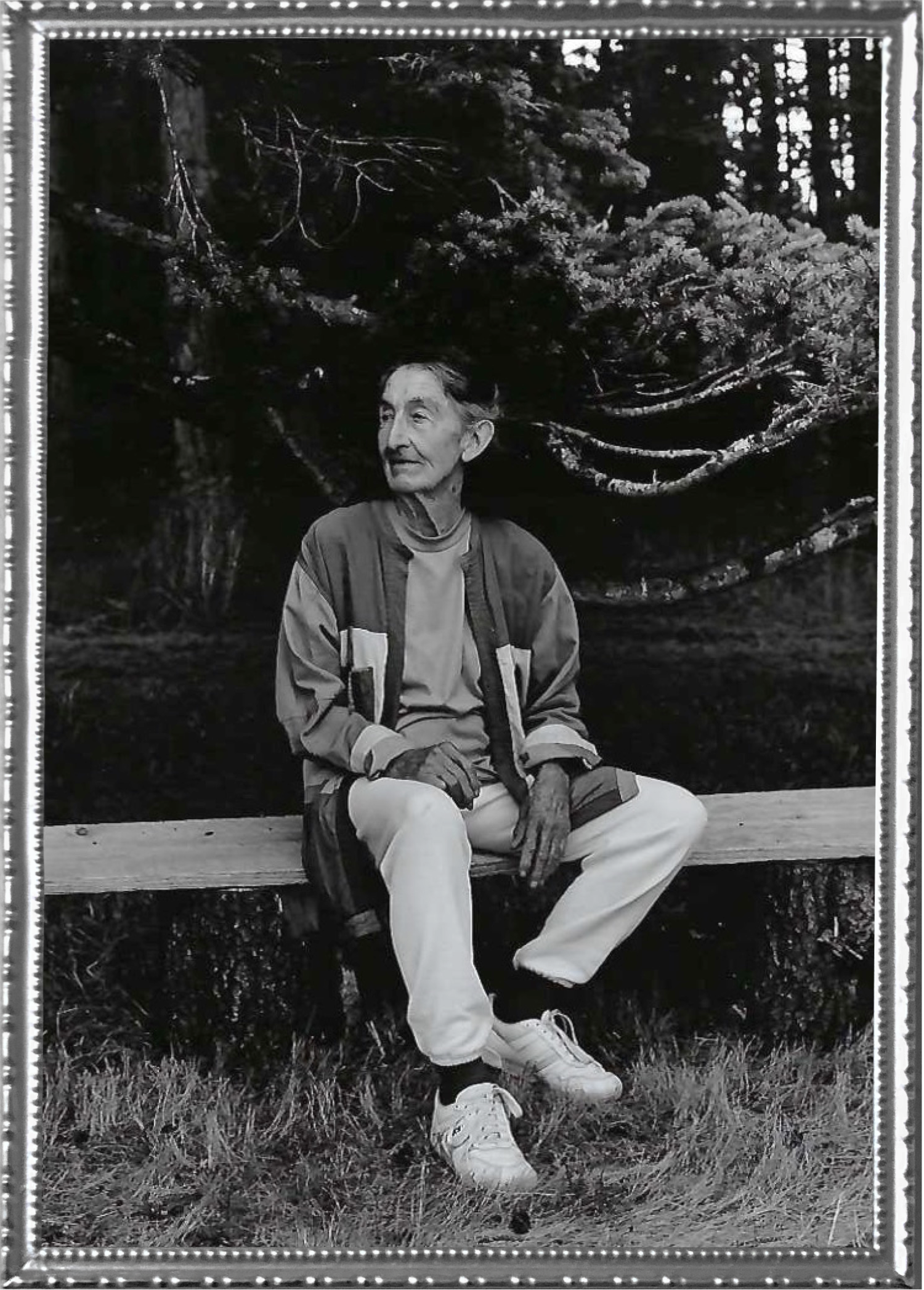

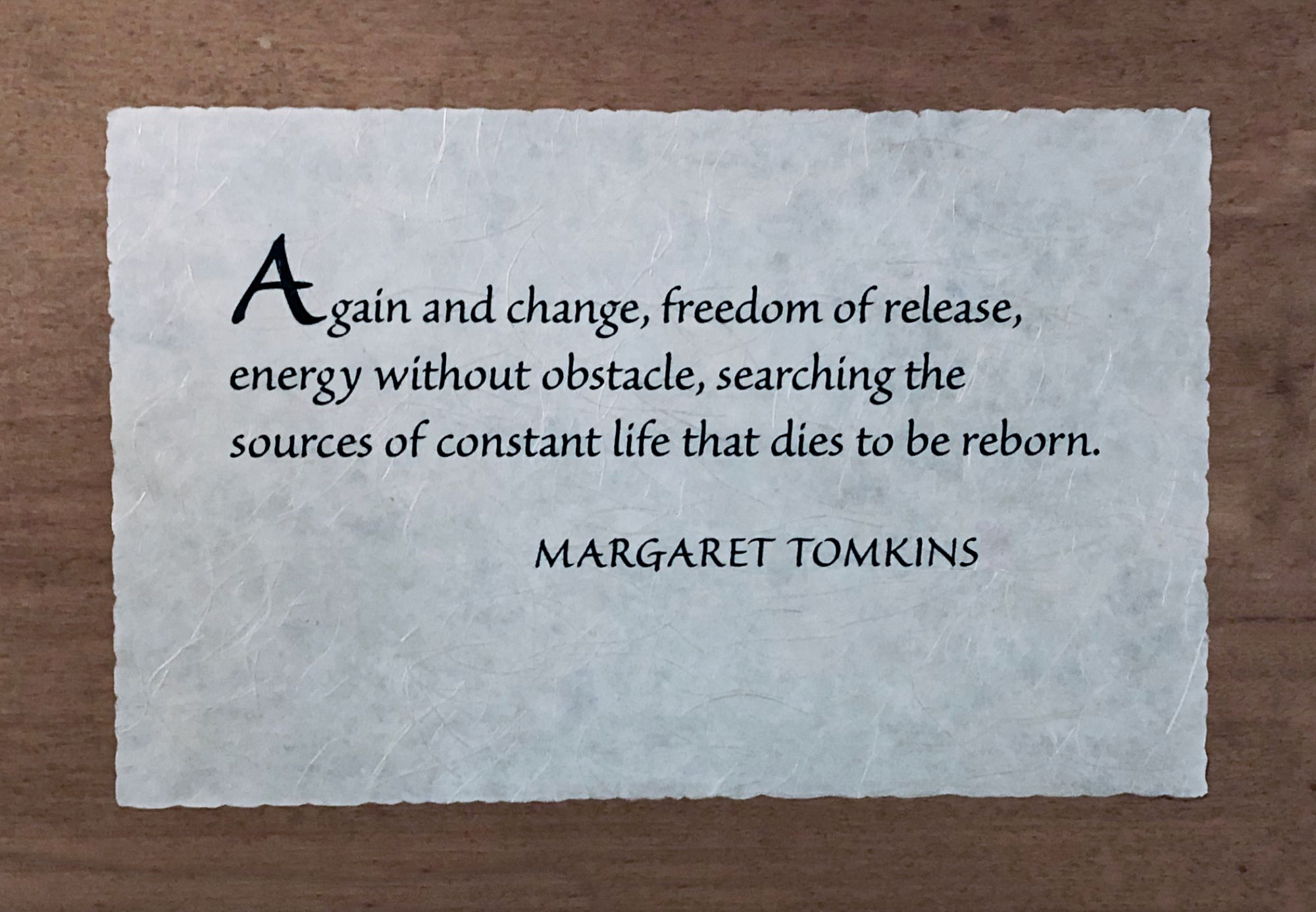

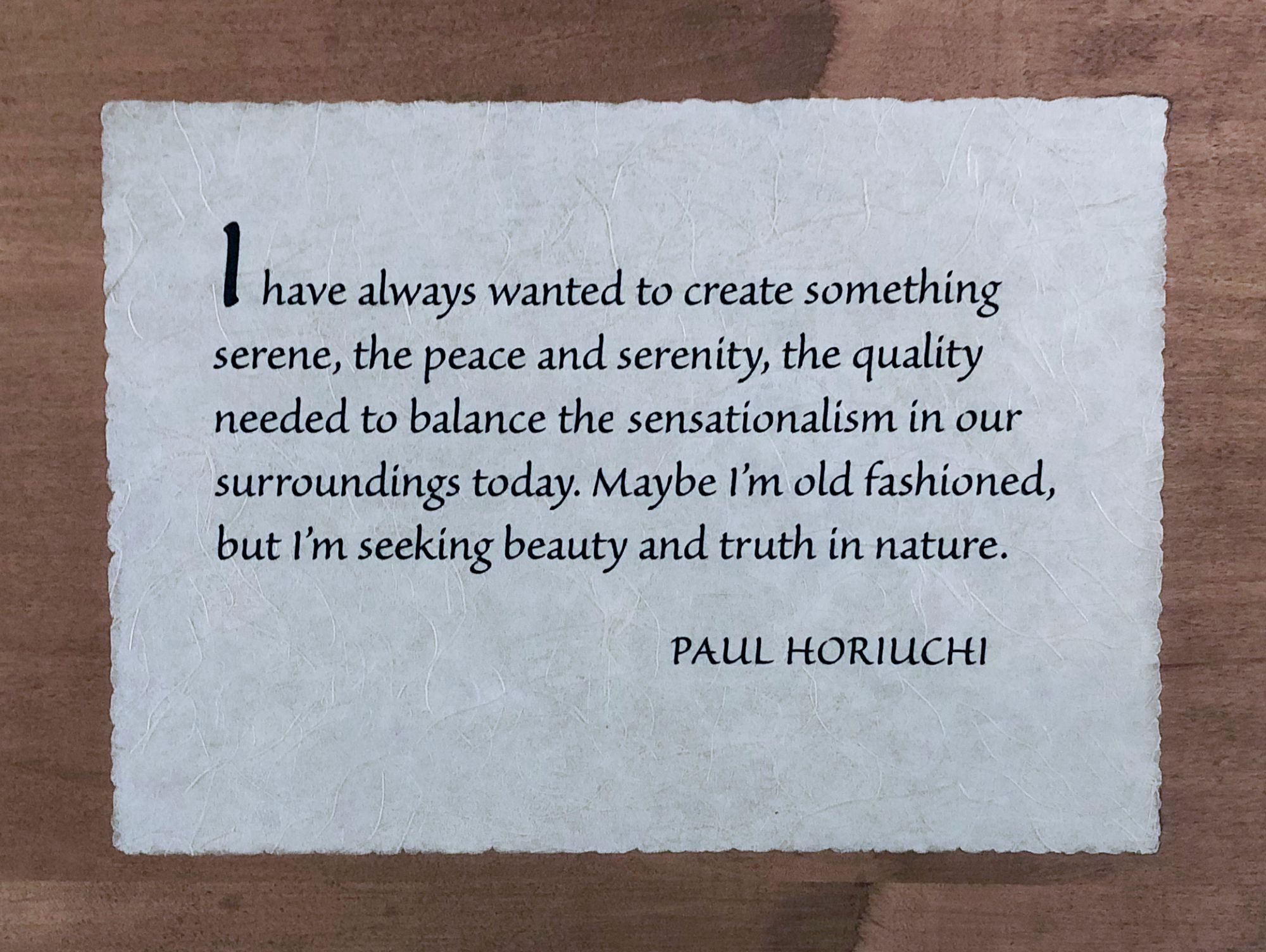

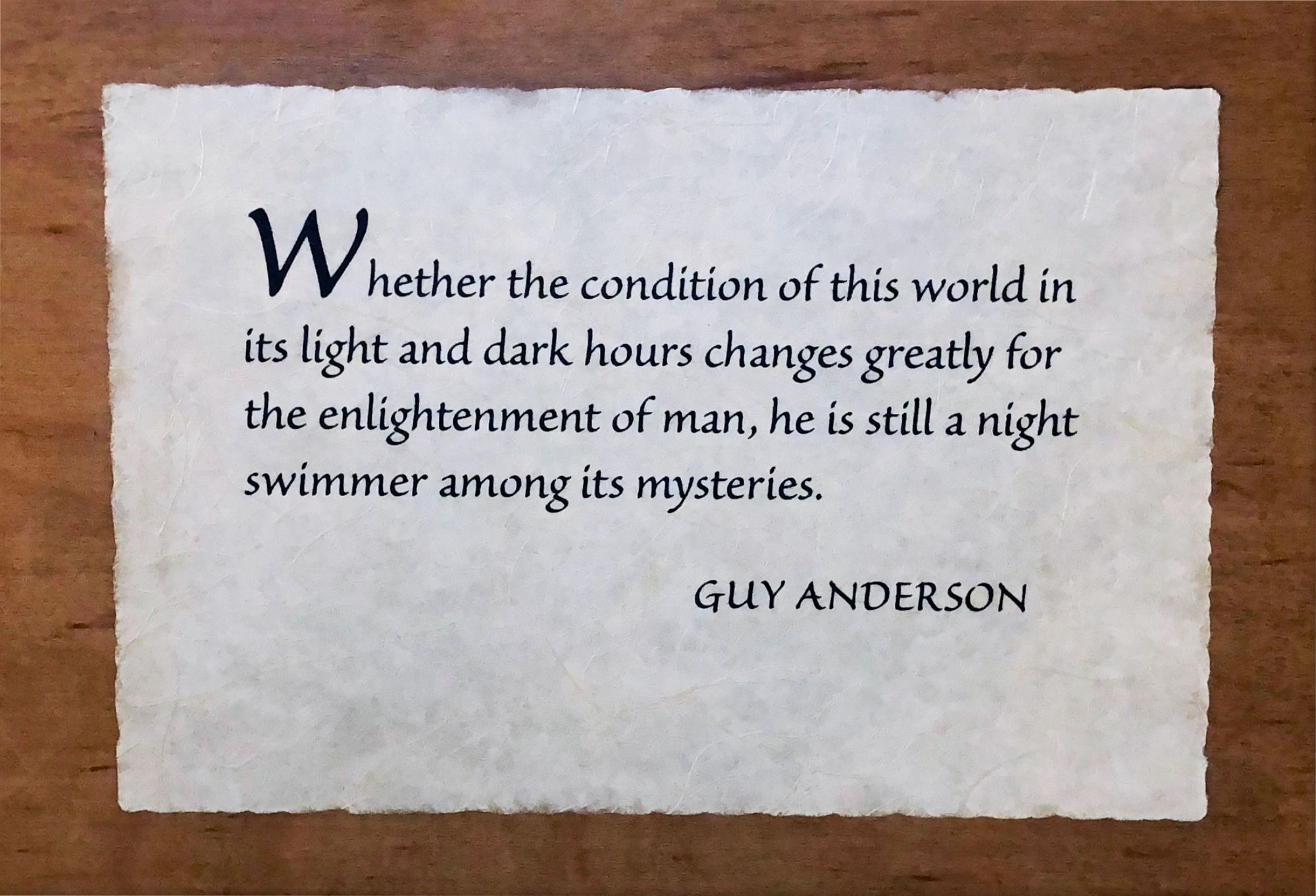

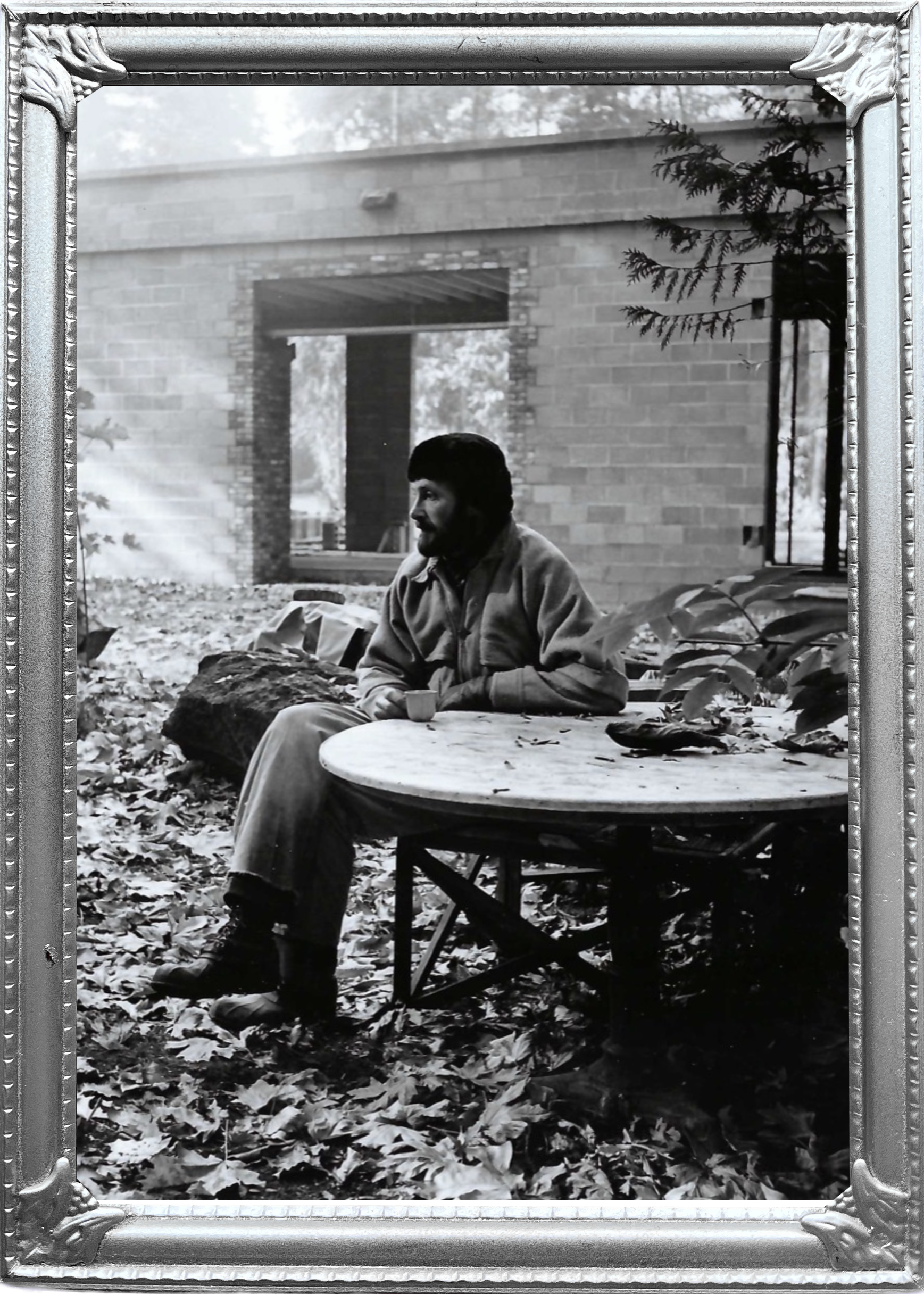

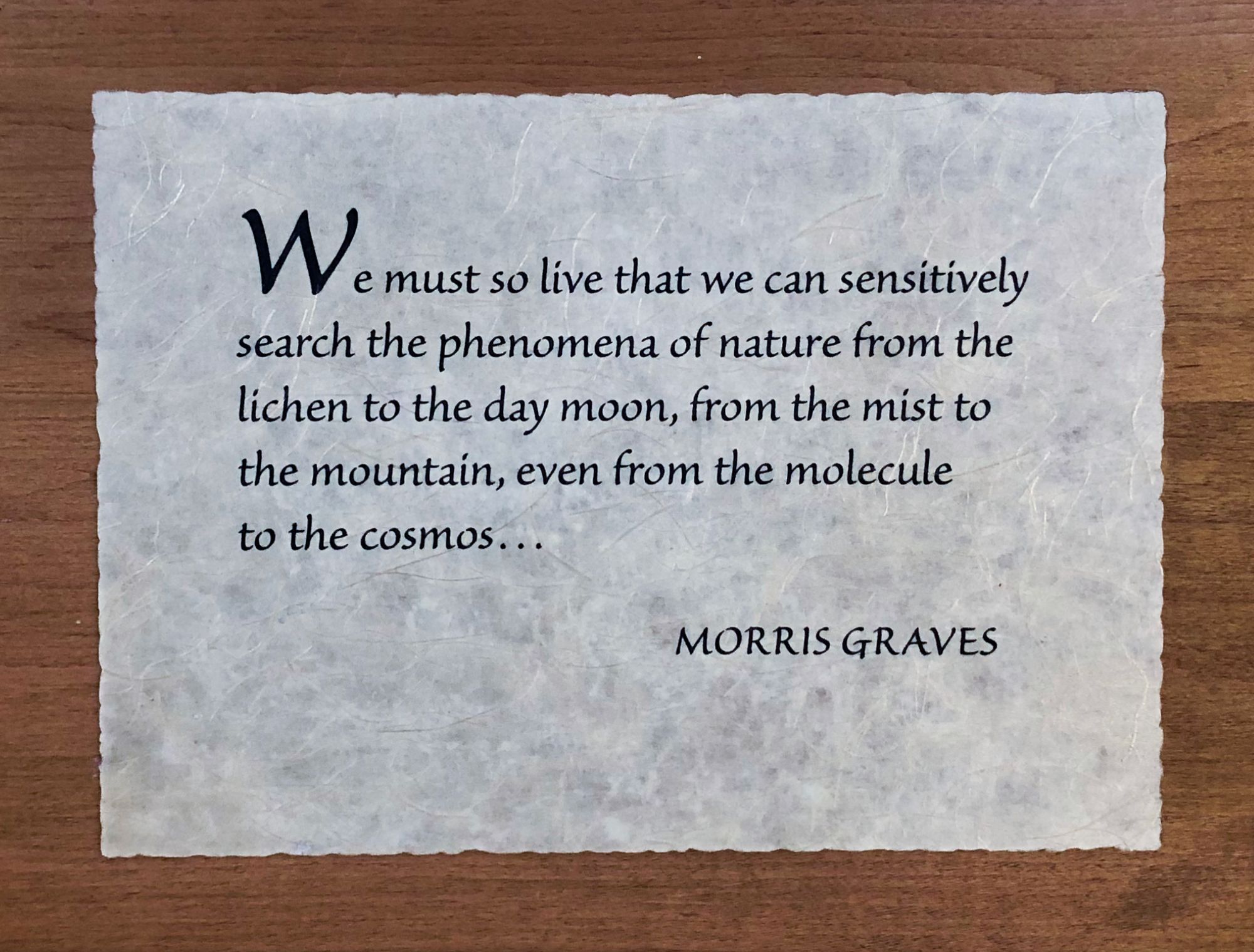

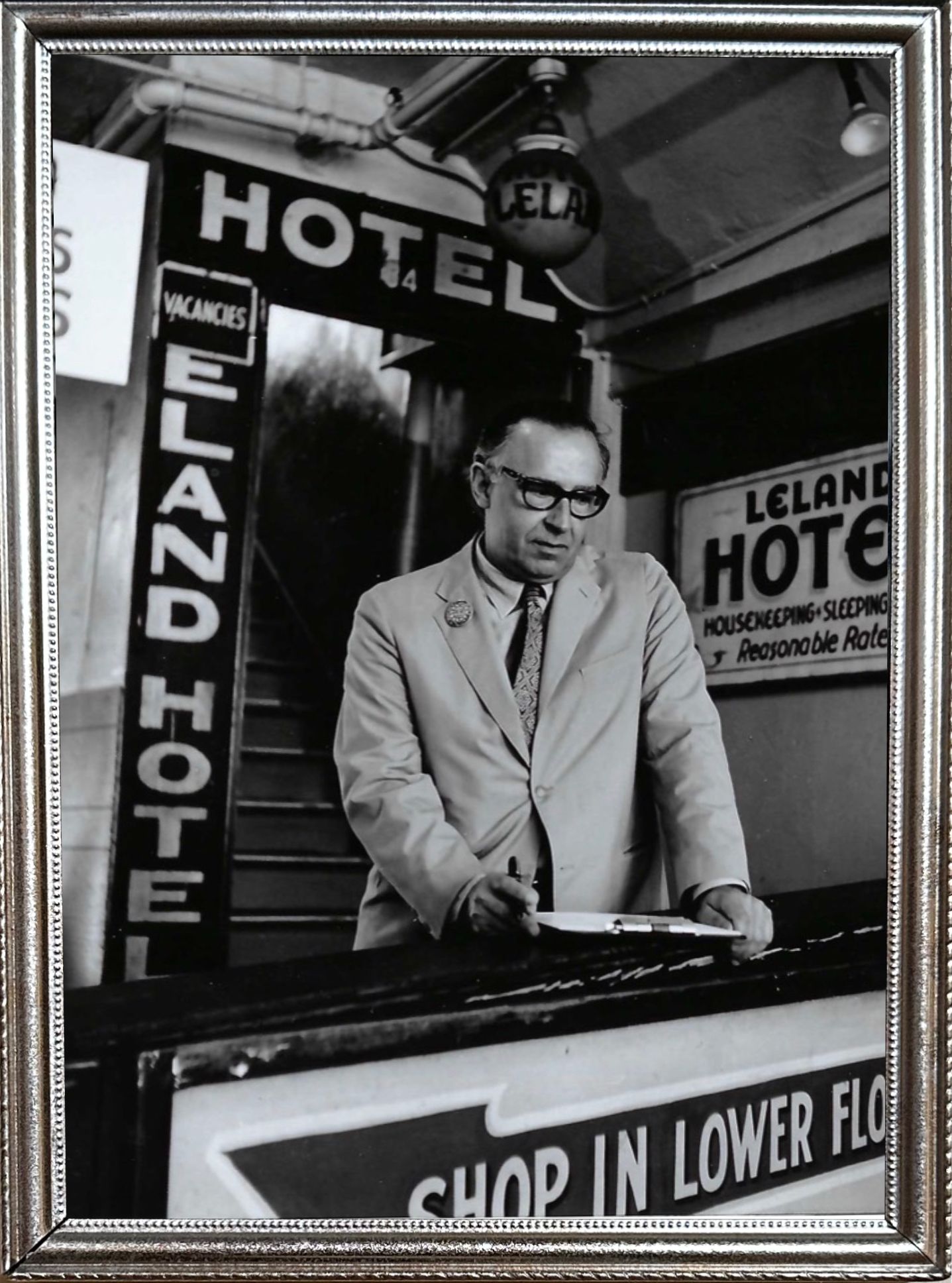

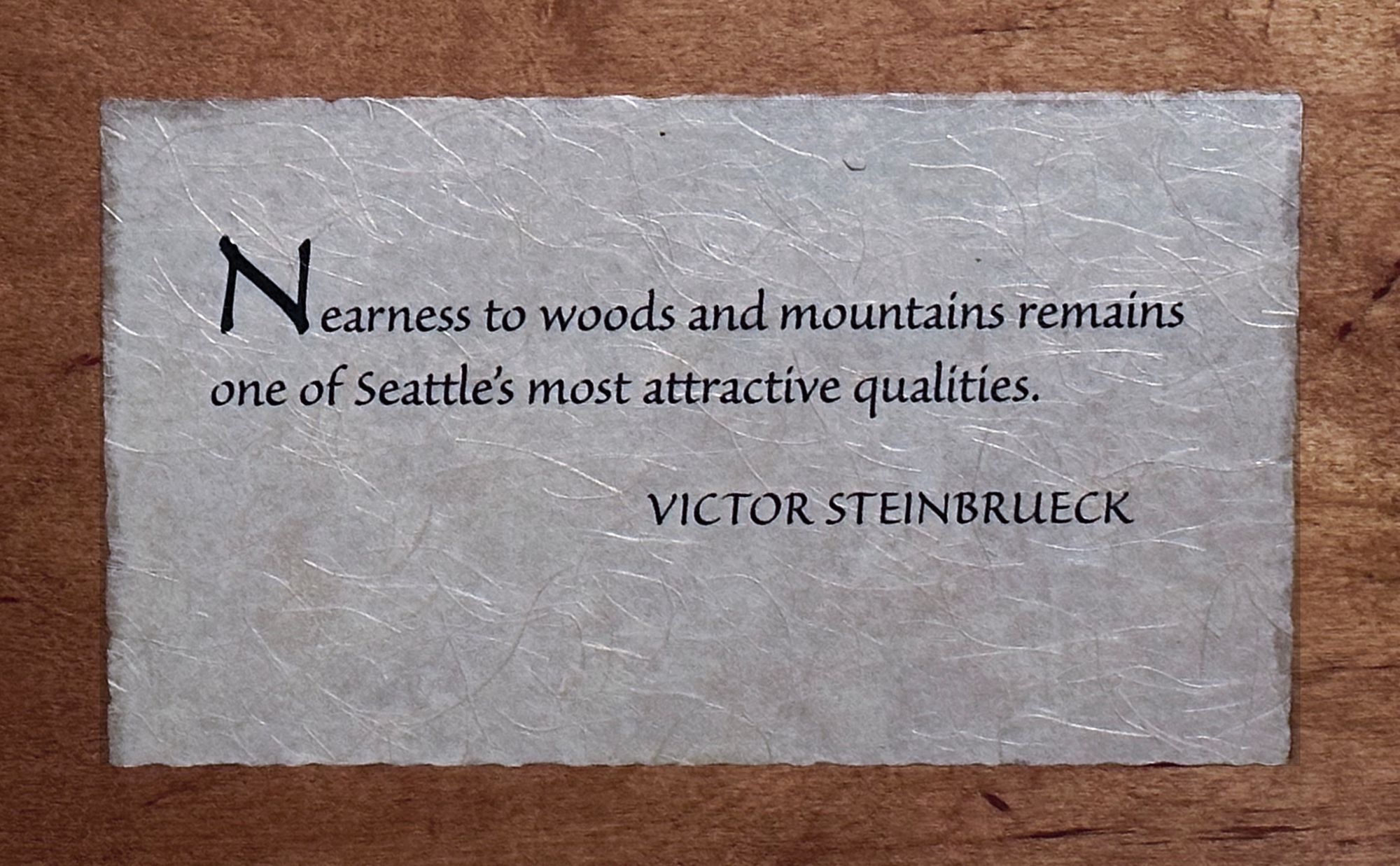

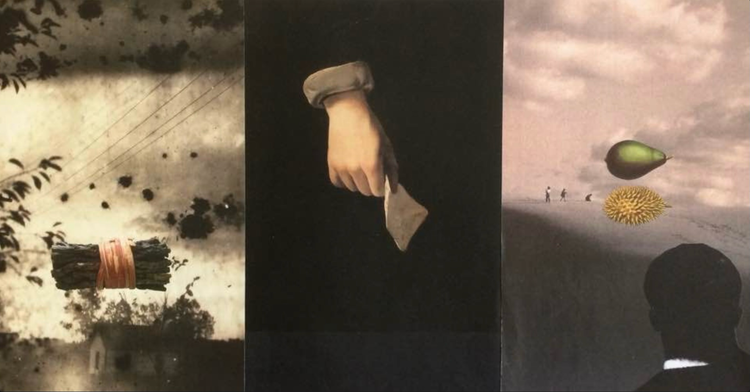

My contribution to the Treewalk was an installation at Betty Bowen viewpoint titled Visionary Voices, which honored Betty Bowen and the artists she had supported. From my research I chose several quotes that illuminated the personal art philosophy of each artist. I then laminated the quotes to a small wooden plaques and placed them in front of the artists'concrete artworks. I also commissioned Irisdescent Light photographer and co-author Mary Randlett to create copies of her artist portrait originals, which I inserted into silver frames set on the plaques. Finally, to draw attention to artwork that had been clearly visible but often unnoticed at the viewpoint since 1978, I surrounded each artist’s concrete design with a portable wooden frame. The feature image of this journal post shows a panorama of my Visionary Voices installation.

Photographer Mary Randlett was present at the first Visionary Voices installation on the day of the Treewalk in 2003, and excitedly described the event as “a Happening.” Docents at the installation reported that many neighborhood walkers who stopped to view the installation insisted that even though they had lived on Queen Anne “forever,” they had never seen the concrete artist designs before the day of the Treewalk. But wooden frames around each of the artists' cast concrete designs—accompanied by artist portraits and personal quotes—brought the artists' legacy, along with Betty Bowen’s, into more inspiring focus.

The gallery layout that follows summarizes the life and philosophical focus of each Visionary Voices artist, accompanied by close-up photos of the concrete art panels they created in 1978:

Margaret Tomkins

Although she abhorred the “mystic painter” label applied to her contemporaries Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, and Guy Anderson, Margaret Tomkins’ own abstract work carried with it a vibrant, enigmatic, and mystic tone of its own. More highly-colored than the work of most Northwest nature-inspired artists, her work sang with a clear and powerful vibrancy. She lived alone for many years in a hand-built, seacliff house on Lopez Island in the San Juans, disdaining all followers and sycophants, continuing to paint until her death in 2002 at the age of 85.

Mark Tobey

Mark Tobey is generally regarded as being the founder of the mystic “Northwest Style” of painting, rooted in the landscape and taking inspiration from the wealth of Asian influence that abounds in Seattle. His most famous paintings were in the “white writing” style he developed, in which thousands of delicate, interlacing white calligraphic-like lines undulate with frenetic life against subdued background color. The effect was abstract, deeply symbolic, and reminiscent of the spontaneous vibrancy of Asian brush painting.

Harold Balazs

At various points in his long career as a professional artist, Harold Balazs has been a sculptor, a painter, an enamelist, a jeweler, a woodcarver, a calligrapher, and a public artist specializing in large -scale architectural pieces. His architectural sculpture commissions can be seen all over the Northwest and abroad. His work and his life reflect an insatiable curiosity and joy of creation.

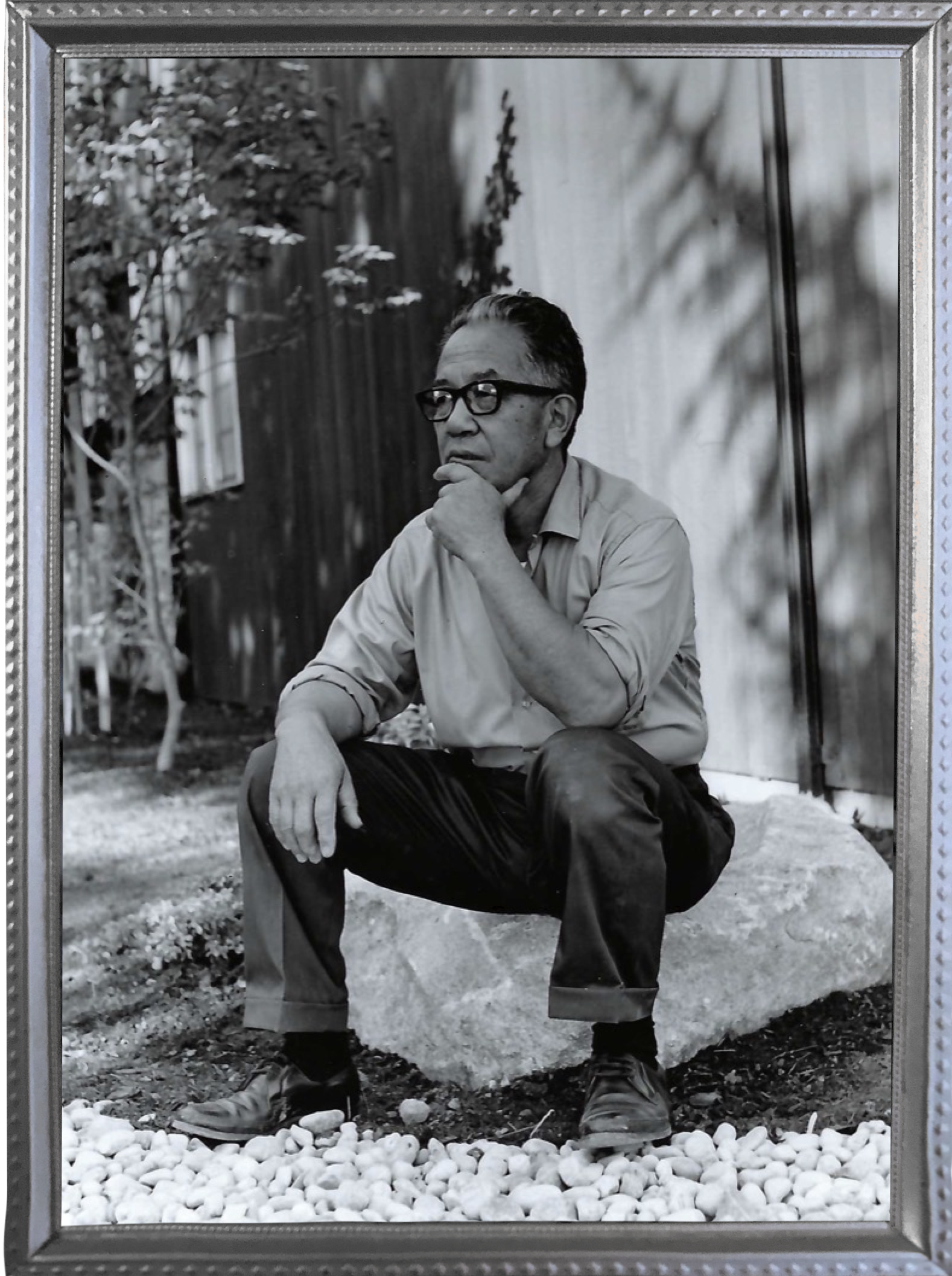

Paul Horiuchi

In his own words, Paul Horiuchi always wanted to create “something very quiet” in his paintings and collages. He was deeply influenced by the aesthetics of his Asian ancestral roots. One word that describes best his overall tone is simply “elegance.” His work combines the refined nuances of a subdued Northwest color palette and the tactile, luminous, metallic tone of Asian lacquers and ceramics. He is best known for the large-scale paper collages and mosaics of his later career.

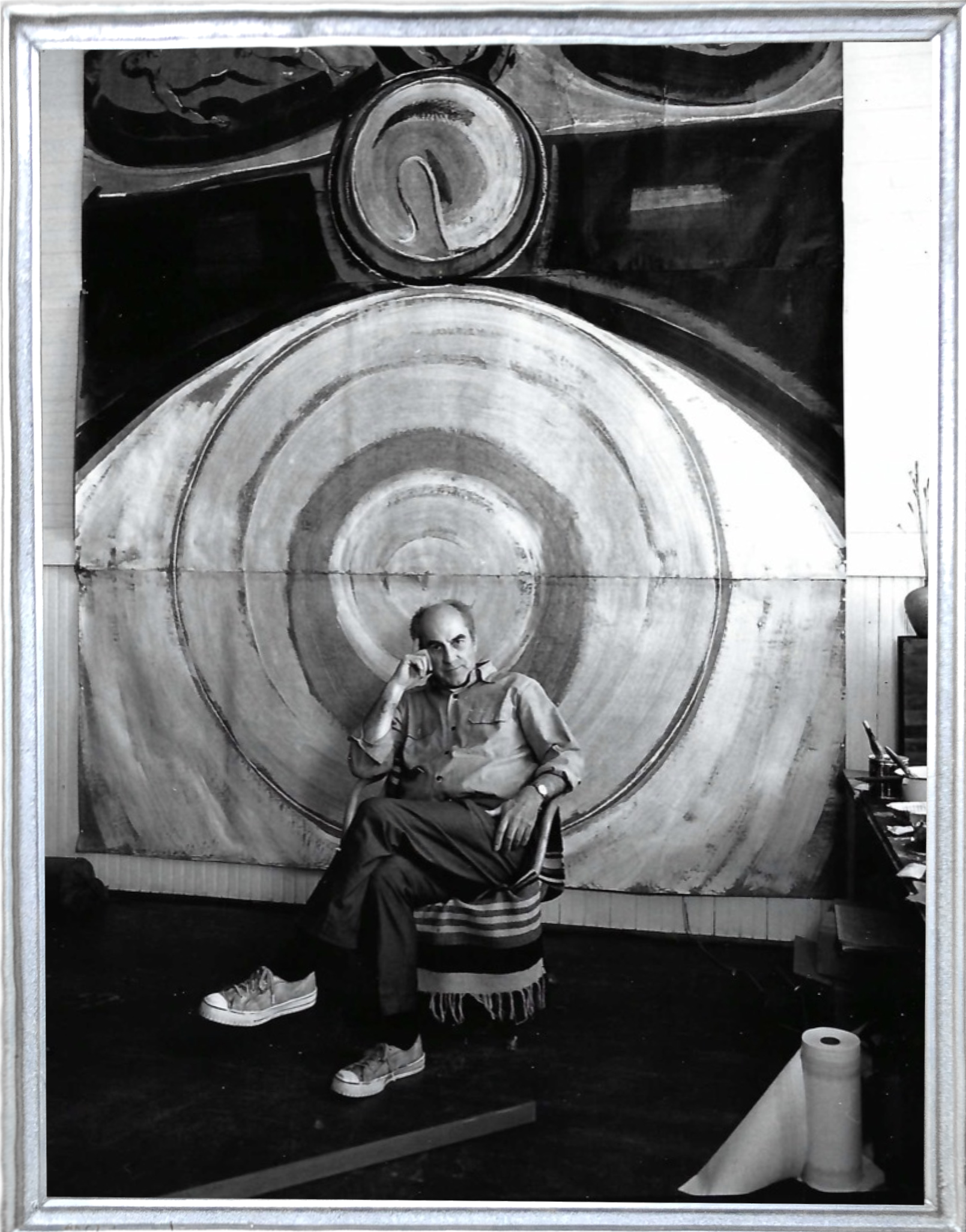

Guy Anderson

Anderson’s large, dynamic, often somber paintings in a subdued palette of rust, charcoal, umber, and milky white, combined his deep understanding of Eastern art philosophies with motifs patterned on the vigor of Northwest coast native art. A mystic to his core, Anderson’s paintings carried with them the ambiance of Puget Sound’s misty light, mountains, and woods. The focus of his paintings was nothing less than man’s place in nature and the cosmos. He lived most of his professional life in La Conner, in the Skagit valley.

Morris Graves

Along with Mark Tobey, Morris Graves is perhaps the most well-known of the Northwest “mystic” artists who were deeply influenced by the philosophies of Asian art. Like Tobey, he was drawn to a more eastern aesthetic in which personalized expressions are tied to cosmic themes. He often worked on paper, with a delicate and moody palette, filled with enigmatic symbols from nature (birds, flowers, feathers) the captured the fleeting evanescence of life itself.

Victor Steinbrueck

Best known as the architect whose passionate, progressive, and civic minded ideals helped preserve the Pike Place Market as a vibrant and colorful core of Seattle life, Victor Steinbrueck was always an artist at heart. He began a practice of daily sketching during the Great Depression, when the Federal government employed out of work artists, designers, and engineers to build roads and parks for public benefit. During his years as a professor of architecture at the University of Washington, his Seattle home was always a hub of activity for many artists who later became famous. With these associations, several of Steinbrueck’s artist friends were commissioned to create the cast concrete artworks that were part of his redesign of the viewpoint at Queen Anne’s Marshall Park. The park incorporated the artworks into what is now known as Betty Bowen Viewpoint.

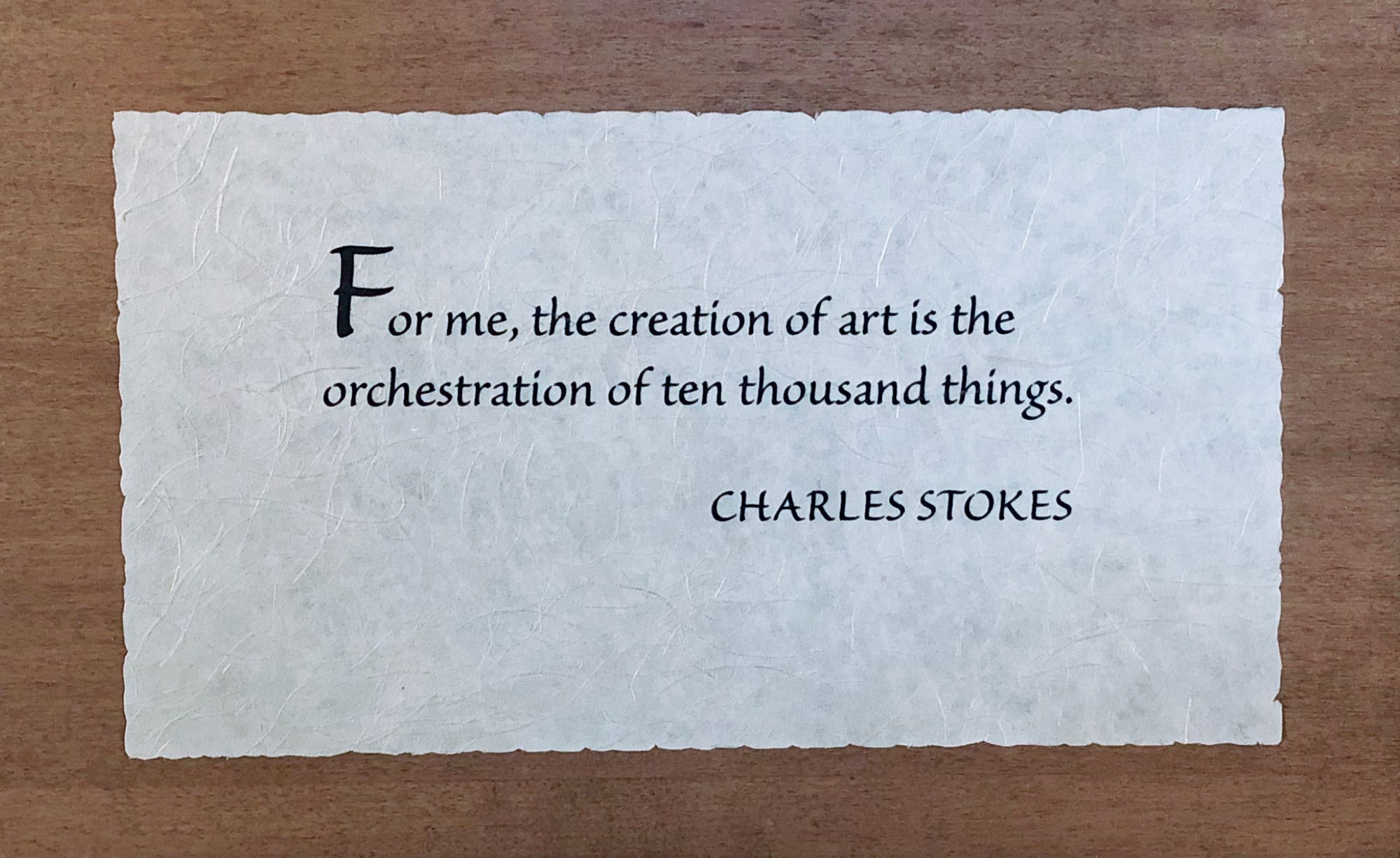

Charles Stokes

One of the most enigmatic of the eleven Visionary Voices artists, Charles Stokes paintings defy rigid categories. They could be based on natural geometry or his own inner visions, but were always refined, serious and compelling. Mr. Stokes taught art for fourteen years at Cornish School before leaving his Seattle affiliations and moving permanently to New York City.

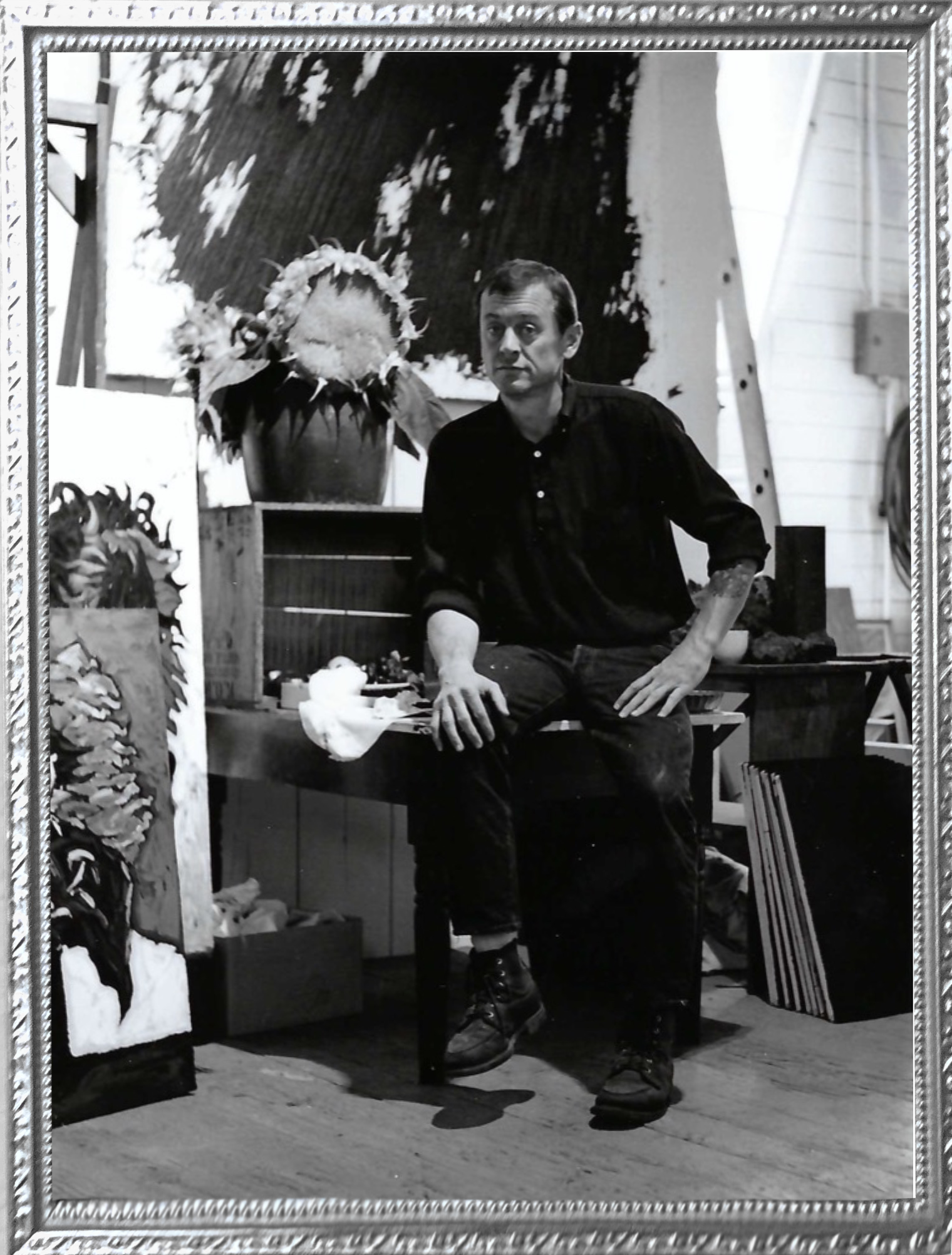

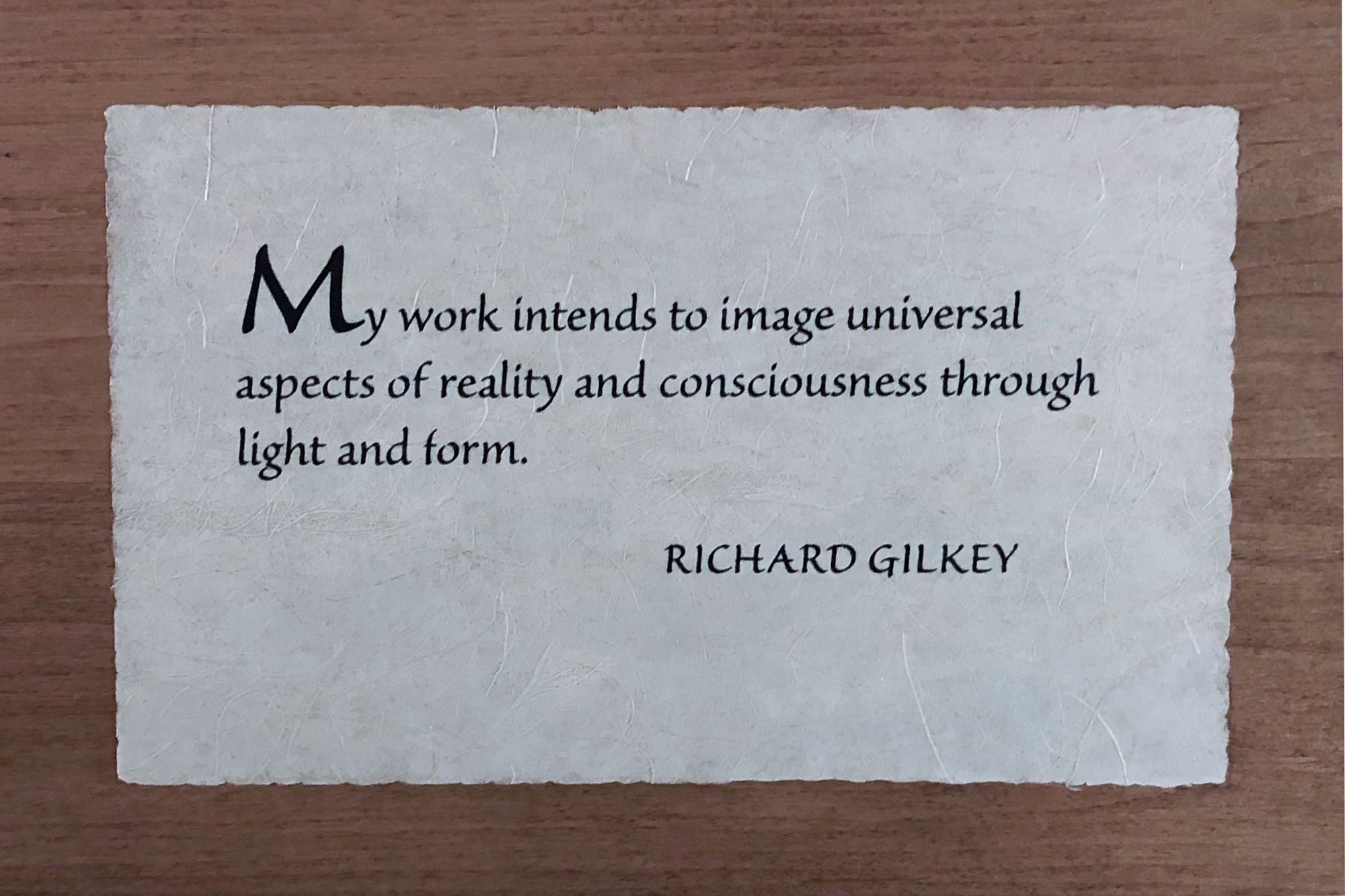

Richard Gilkey

Best known for his luminous paintings of the Northwest landscape in the Skagit valley, the paintings of this moody, volatile WWII veteran often suggested the invisible life essence that exists beneath the surface of visible reality. He believed that artists have the potential to advance a heightened perception of reality through their work, and through this process, they may enhance both art and the art of living. His later paintings left literal representation behind and grew more abstract, focusing more on illuminating the essence of pure consciousness.

Leo Kenney

Leo Kenney’s artistic career evolved from his youth as a child prodigy to his mature years as a painter of luminous, radiant, jewel-toned representations of what he termed “the Mysteries” that integrated microcosmic and macrocosmic worlds. Kenney himself described his work as “living geometry” because of its meticulous depictions of circular, almost cell-like design motifs vibrating with life energy. Always inspired by the sublime order that reveals itself in the structures of nature, Kenney says simply, “I don’t paint nature. I paint about nature.”

James Washington Jr.

Although he had no formal training in art, visionary artist James Washington Jr. is regarded as one of the most celebrated Northwest sculptors. As a young man he worked with pastels and watercolors. On a trip to Mexico, he brought back a stone that seemed to have a unique presence. He brought the rock with him on his return trip. Back in Seattle, he decided to sculpt its inner life. The result was so powerful that he began to focus primarily on stone sculpture, always striving to be a visible voice for the inner, invisible essence of this natural, but life-charged material. His work reveals a constant dialogue between spirituality and creativity.

For many years after the Queen Anne Treewalk ended, I continued my weekly walks up the secluded City stairway to listen to the fountain and admire my favorite home.

On my usual walk past the home one day in 2021, I noticed a Sotheby’s “For Sale” real estate sign just outside the front door. The online listing included a history of the home—which had belonged to a “well-known Seattle art patron.”

The name of the patron was Betty Bowen, whose mysterious, Asian-inspired home had provided me with a subconscious prelude and a portal to guide me to a location just a block up the hill where–many years in the future–my existing, Asian-inspired world view would eventually expand into the Visionary Voices installation I created.

A special mystery accompanies cast concrete mosaic #4, which is attributed on the site map at the Viewpoint to artist Kenneth Callahan. My notes from 2003 indicate that the mosaic art design was created by Paul Horiuchi. I designed a quote plaque for Paul Horiuchi and included him in my mini-biographies. If any reader has information that can clarify who the real creator was of that mosaic, please let me know in the comments.

Member discussion