Wine Wisdom

A wise man once said:

“It is well worth remembering that there are five reasons to drink good wine: the arrival of a friend; one’s present thirst; one’s future thirst; the excellence of the wine; or any other reason.”

— Anonymous

It is the end of October 2024 and for weeks now, Yakima area farmer Phil Cline has been overseeing preparations for this year’s grape harvest here in central Washington state. In this post, I’ll be sharing some of Phil’s behind-the-scenes insights about the art of wine-making—and the intricate and laborious process that transforms grapes into “good” wine.

Phil is both a dedicated grower of grapes and an enthusiastic educator about viticulture, terroir, and the subtle nuances of various wines. His agricultural philosophy reflects a dedication to sustainable, salmon-safe, and organic growing methods that provide the highest quality source material for his winemaking clients—and for his own wines with the Naches Heights label.

Phil is especially proud of his lobbying efforts to establish the area of “Naches Heights” as its own, unique “AVA.” The term is an abbreviation for “American Viticultural Area,” and refers to a specific vineyard zone based on geography and climate. The Naches Heights AVA exists within the larger climate zone of Yakima, Washington, and many of the farmers within this AVA adhere to sustainable or organic agricultural practices.

The vineyards shown in the photo below are some of Phil's prized, certified organic grapes that are grown without herbicides. Instead, the focus in on providing an excellent environment for the soil and the microorganisms that feed the roots. These organic soil "helpers" include companion plantings of yarrow and milkweed, shown in the foreground.

Following the “early to bed and early to rise” traditional farming protocol, Phil Cline always seems to project an air of positive-spirited love for his chosen profession, no matter what challenges may come his way. He understands that the art of grape growing follows techniques that have been handed down for centuries by farmers throughout the world. He appreciates that modern means of transporting and processing harvests can help make a farmer’s life less stressful. But he also knows that most of the care throughout the growing season still needs to be done entirely by skilled human hands.

Grape Growing and Farm Life, Then and Now

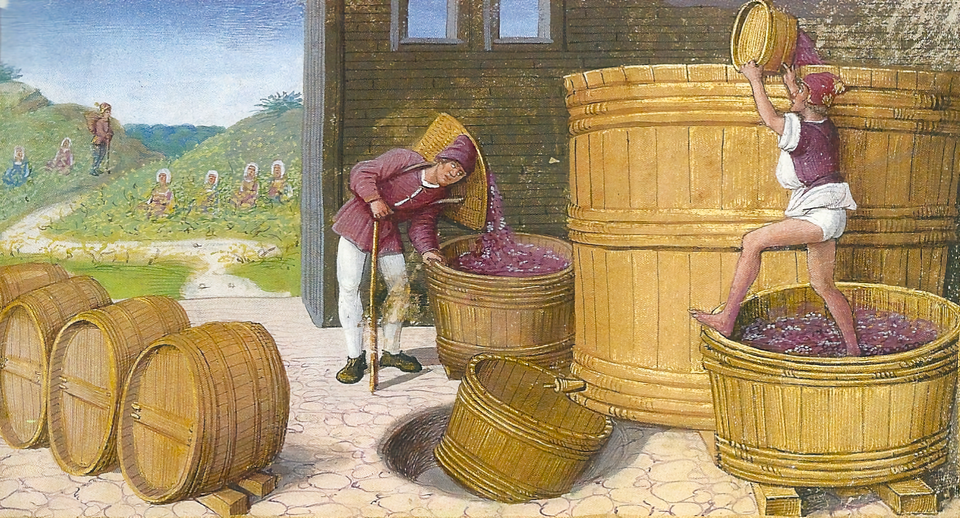

In the gallery below, I’ve included several illustrations by French artist Jean Poyet, who lived and worked in Tours, France, during the 15th Century. His paintings document the agricultural techniques that were common in that era.

I’ve accompanied many of these paintings with Phil Cline’s own photos and videos, which show how his work in 2024 frequently mirrors many of the farming traditions that Poyet illustrated.

January

But first, one must get through the cold, dark winter…

February

A midday meal of bread, cheese, and dried fruit is accompanied by a glass of wine for the master of the house.

March

In the cold, early months of March, work begins outdoors with the pruning of the grapevines. Workers trim the leafless vines growing on the hillsides along with those trained on the overhead arbor.

And here is Phil's 21st century version:

April

The land is green and alive in the Loire valley in late spring, and daily life for the landowning, “leisure class” is far from laborious. In this painting, a privileged youth in resplendent clothing provides flower specimens for his sweetheart’s garland:

May

As the fruits of vineyards and orchards continue the long journey to maturity, the flowering trees on the farm unfurl their blooming treasures. Another richly-dressed couple fill their arms with cut branches before strolling back to the manor house.

June

As summer begins, 15th century village work crews begin cutting and stockpiling hay for the farm animals. Although Phil Cline’s 21st century farming work does not include animal husbandry or grain growing, he and his crew intersperse vineyard duties with the care they provide (year-round) for the organic pear, apple, and hazelnut orchards that Phil owns or manages.

July

A farmer’s work is never done. In Poyet’s midsummer painting, work crews cut the ripe wheat that will provide bread for the next year.

August

The piles of cut wheat stalks are transported to the threshing barn by ox cart:

Inside the threshing barn, the wheat seed kernels are loosened from their stalks so they can be winnowed, separated from the chaff, and ground into flour.

September

Rotating, hand-cranked millstones (similar to ones used in the 15th century) grind wheat for winter bread.

October

In the videos that follow, Phil Cline outlines the intricate process of daily “grape sampling” that determines the best time to begin the actual harvest.

Towards the end of October, the grapes have reached maturity and harvest finally begins. Phil's longtime foreman, Abraham, and his wife, Lupe, oversee quality control for the harvest.

In the 15th century, the grapes are crushed by foot and the resulting juice is transferred to large vats for dispensing into storing and aging barrels. In the 21st century, the grapes are transported to commercial processing facilities, where they are crushed by machine, stored in stainless steel tanks, and also aged in barrels.

Grape Growing Triumphs

What are the cumulative results of careful planting, training, and pruning of the grapevines, testing for sugar levels, monitoring of weather patterns that can spell success or disaster, and making the final decision about when to harvest?

Phil Cline’s many award-winning wines tell the story:

Here's to all the farmers making a difference, one harvest at a time!

— Phil Cline, farmer and vintner

Final Thoughts and Recommendations

“Good" wine is an almost magical, physical distillation of the winemaker’s dedication, and should be consumed with respect, gratitude, and a sense of responsibility.

To gain more knowledge about the history of winemaking, the grape varieties that are associated with specific regions, and the food pairings that best accompany each wine, I highly recommend the book I purchased more than twenty years ago when I began my own wine appreciation journey. Titled The Wine Bible, by Karen MacNeil, it is included in the “resource” section below this post.

To provide you with an example of Ms. MacNeil’s storytelling approach—which does not include the elitist language that many wine “experts” adopt —I close this post with a brief, sneak preview anecdote from her book:

On a trip to the Piedmont region of Italy, where wine and food orders are traditionally accompanied by a vast array of “preliminary” food delicacies before the main meal begins, Ms. MacNeil reacted to this unexpected, culinary “overabundance” with audible groans of alarm. The seasoned waiter smiled, set down the last dish, and dispensed the following wise advice:

In Piedmont, you have to eat! If you want to diet, go to France!

Naches Heights Vineyard focuses on growing the best quality wine grapes to provide our winemakers with exceptional ingredients. We believe that great wines start in the vineyard, influenced by the unique combination of soil, water, light, and human touch known as Terroir. We cultivate grapes in two distinct American Viticulture Areas (AVAs): the established Yakima Valley and the newer Naches Heights AVA, which we helped establish in 2008.

The Wine Bible is a comprehensive, entertaining, beautifully written, and endlessly fascinating celebration of all subjects related to wine. This completely updated 3rd edition includes detailed location maps of wine growing regions throughout the world, accompanied by tasting notes for different grape varieties, personal anecdotes, and over 400 photographs in full color, plus a fully revised “Great Wines” section. (Available on the author's site and at Amazon.)

Member discussion